Abstract

We produce novel empirical evidence on the relevance of temperature volatility shocks for the dynamics of productivity, macroeconomic aggregates and asset prices. Using two centuries of UK temperature data, we document that the relationship between temperature volatility and the macroeconomy varies over time. First, the sign of the causality from temperature volatility to TFP growth is negative in the post-war period (i.e., 1950–2015) and positive before (i.e., 1800–1950). Second, over the pre-1950 (post-1950) period temperature volatility shocks positively (negatively) affect TFP growth. In the post-1950 period, temperature volatility shocks are also found to undermine equity valuations and other main macroeconomic aggregates. More importantly, temperature volatility shocks are priced in the cross section of returns and command a positive premium. We rationalize these findings within a production economy featuring long-run productivity and temperature volatility risk. In the model temperature volatility shocks generate non-negligible welfare costs. Such costs decrease (increase) when coupled with immediate technology adaptation (capital depreciation).

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

There is near unanimous scientific consensus that climate change affects human health, behavior, and activity (Patz et al. 2005; Deschênes and Moretti 2009; Zivin and Neidell 2014; Cattaneo and Peri 2016) and has a negative impact on economic development (Stern 2007; Hsiang and Meng 2015). Over the past decades, the economic risk of climate change has been quantified by means of the so-called Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs). In this class of models climate change effects (costs and benefits) are captured via damage functions. IAMs easily allow to relate climate variables (e.g., temperature, sea-level rise, rainfall, \({\text {CO}}_{2}\) concentration) to economic welfare. However, even if widely used, IAMs have been subject to severe criticism. Above all, IAMs have been questioned to have no empirical supports (Pindyck 2013; Diaz and Moore 2017). Moreover, Pindyck (2013) argues that the use of IAMs as a climate change policy tool faces a major problem: “the modeler has a great deal of freedom in choosing functional forms, parameter values, and other inputs, and different choices can give wildly different estimates of the social cost of carbon and the optimal amount of abatement”. In other words, he points out that IAMs can deliver any result one desires. In the end the crucial flaws of IAMs make them “close to useless as tools for policy analysis” Pindyck (2013) (pag. 860). Another important issue is that IAMs focus exclusively on level effects rather than on growth effects. However, distinguishing between level and growth effects is of first order importance. Actually, the effects on the growth rate compound over time are more quantitatively important than effects on the level of output (Dell et al. 2012; Pindyck 2013; Colacito et al. 2019). Finally but equally importantly, existing climate change models (and in particular IAMs) have paid little attention on other macroeconomic variables (e.g. productivity growth, investment growth, labor supply and capital accumulation) other than GDP (see, for example, Revesz et al. 2014).

To address some of the issues associated with the use of IAMs to examine the economic costs of climate change, more recent analyses have incorporated empirical evidence indicating that rising temperature levels have a negative impact on the real economic activity (Dell et al. 2012; Du et al. 2017; Colacito et al. 2019) into Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models (Bansal et al. 2016; Donadelli et al. 2017). Empirical findings and quantitative model-based results confirm that a rise in the average temperature level has a negative impact on the growth rate of key macroeconomic aggregates (e.g., productivity, investment and consumption growth) and equity prices. However, as also pointed out by Diaz and Moore (2017), both standard IAMs and recently developed temperature-related DSGE models typically estimate the effects of equilibrium changes in average temperature levels (or in average rainfall levels), but not necessarily the effects of extremes (persistent heatwaves) or stochastic variability (storm surges). The impact of climate change may be actually the result of variations in both the mean and the standard deviation of climate drivers (Rind et al. 1989; Mearns et al. 1996). By focusing exclusively on changes in the mean, the overall and true impact of climate change on human activity could be seriously underestimated (Katz and Brown 1992; Schär et al. 2004). For example, fluctuations in climate conditions at the inter-annual time scale represent important drivers to capture extreme weather events such as multi-year droughts (Peel et al. 2005) and water scarcity (Veldkamp et al. 2015). In this respect, Elagib (2010) and Ito et al. (2013) show that intra-annual temperature variability is associated with extreme air temperature. Moreover, changes in the intensity of extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, are highly sensitive to shifts in intra-annual temperature variability (Fischer and Schär 2010). Thus, other than mean values, the dynamics of volatility in climate drivers may be relevant for the understanding of extreme events, and, consequently, for the impact of climate change on the real economic activity (Brown and Lall 2006). In other words, climate change as well as weather variability are both partly to blame.

Supporting the view that volatile climate conditions matter, some studies have examined the relationship between weather dynamics and fluctuations in consumer spending. Heavy rain, snow, and other extreme events are factors forcing people to stay home. This in turn would lower sales (Parsons 2001). Broadly, the idea is that highly volatile weather conditions may impact consumption decisions (Starr-McCluear 2000; Lazo et al. 2011). Another stream of research argues that the effect of weather on consumer spending is mediated by mood. High variability in weather conditions has a negative impact on mood. For instance, Spies et al. (1997) and Murray et al. (2010) empirically observe that people in good mood tend to be more willing to buy consumer goods than those in bad moods. In a similar spirit, another branch of literature finds instead that stock market anomalies may be the consequence of relevant weather factors (Saunders 1993; Kamstra et al. 2003; Cao and Wei 2005). For example, Kamstra et al. (2003) and Garrett et al. (2005) find that seasonal weather effects (such as the number of daylight hours in a day) tend to influence investors’ risk-aversion.

Taken together, existing empirical evidence support the existence of two channels through which an adverse shock in climate conditions may affect economic factors. The first one operates via the destruction of capital through adverse weather events dampening innovations, output, and productivity (Fankhauser and Tol 2005; Stern 2013). The second one operates via the influence that weather has directly on people mood. Actually, a bad mood due to extreme weather translates into consumption spending (Spies et al. 1997; Murray et al. 2010) and equity investments (Kamstra et al. 2003; Cao and Wei 2005). Loosely speaking, more volatile weather conditions lead to a higher probability of extreme events, which in turn implies stronger effects on investment and consumption plans.

Motivated by this evidence, we examine the effects of volatility in weather conditions on macro-variables and asset prices. Specifically, we investigate both empirically and theoretically whether shifts in the volatility of temperature affect aggregate productivity, economic growth, welfare, and equity prices. While the majority of climate change studies examine the effect of rising temperatures on real economic activity, to the best of our knowledge there is no study focusing on temperature volatility and its macroeconomic effects. With this paper we aim to fill this gap.

Monthly data on UK temperature for the period 1659–2015 are employed to build an intra-annual temperature volatility index. Since both relatively low and relatively high temperature volatility may be harmful, our temperature volatility index is represented by the absolute deviation from an annual benchmark volatility value (i.e., historical average intra-annual volatility observed in the pre-industrial revolution era).Footnote 1 We then employ data on TFP (macro-aggregates, stock market, risk-free rate) for the period 1800–2015 (1900–2015). Empirically, we study the effect of changes in temperature volatility via Granger causality and standard VAR analyses over different historical periods (i.e., 1800–1900, 1900–1950, and 1950–2015). We find that the sign of the causality going from temperature volatility to TFP growth changes over time. By focusing on the 19th century, we find no evidence of a causality between temperature volatility and productivity growth.Footnote 2 For the period 1900–1950, we instead find a significant positive unidirectional causality from temperature volatility to productivity growth. In the post-war period, the direction of the causal effect remains unaltered but not the sign which becomes negative (i.e., temperature volatility has a negative effect on productivity). On one hand, this change in the direction of the causality could be due to the different sectoral structure characterizing the UK economy in different eras. On the other hand, it can be driven by the increasing number of extreme weather events observed over the last three decades. VAR investigations confirm that the way in which temperature volatility affects TFP growth is not constant over time. During the period 1800–1900 no significant effects are detected. Differently, the temperature volatility has a positive (negative) effect over the period 1900–1950 (1950–2015). These results are robust to the inclusion of macroeconomic and financial variables. Over the period 1950–2015, temperature volatility is also found to be detrimental for equity valuations. A battery of cross-sectional asset pricing tests suggest then that temperature volatility shocks command a significant and positive risk premium.

This set of novel empirical facts is rationalized by means of a production economy featuring long-run macro and temperature volatility risk. More precisely, we calibrate the model to match (1) the drop in TFP growth generated by a temperature volatility shock and (2) main UK temperature statistics. Note that we chose the post-war sample since we find the strongest adverse climate economic effects in this period. This is in line with existing evidence documenting negative temperature effects in the post-war period (see e.g., Dell et al. 2012; Colacito et al. 2019). In our production economy a temperature volatility shock gives rise to a negative response of productivity, macroeconomic quantities, and equity valuations, consistent with our novel empirical evidence. In addition, in the model temperature volatility risk commands a positive risk premium. Welfare costs of this type of risk are substantial and amount to 9% of the agent’s consumption bundle in our benchmark scenario. Moreover a rise in temperature volatility is found to have long-lasting negative effects on output and labor productivity growth. Over a 50-year horizon, a single one-standard deviation shock reduces both cumulative output and labor productivity by about 1.0 percentage points (pp). In an economy featuring capital depreciation risk, welfare costs of temperature volatility risk increase when depreciation shocks are positively correlated with temperature volatility shocks, meaning that higher climate variability results in an increasing occurrence of natural disasters, which destroys capital faster. If we allow for adaptation to climate uncertainty by assuming a positive correlation between temperature volatility shocks and long-run productivity shocks (i.e., the economy immediately responds to temperature volatility shocks by boosting productivity), temperature volatility risk produces welfare gains and a drop in the equity risk premium. Needless to say, this evidence suggests that “adaptation” plays a crucial role in reducing the economic costs associated to temperature volatility risk.

Our benchmark production economy features capital and labor dynamics. For reasons of robustness, we also study the macro and welfare effects of temperature volatility shocks in an endowment economy. By calibrating the model to match the main consumption dynamics and the empirically observed impact of temperature volatility shocks on consumption growth, we find qualitatively and quantitatively similar results.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we review the related literature. Section 3 presents the main empirical findings concerning the effects of temperature volatility shocks on macro and financial aggregates. In Sect. 4, we describe our production economy featuring temperature volatility risk. Section 5 presents the quantitative results. To shed light on the robustness of the quantitative implications of temperature volatility shocks, we analyze an endowment economy in Sect. 6. Section 7 concludes.

2 Related Literature

Our study is primarily related to the most recent empirical and theoretical literature examining the effects of climate change on macroeconomic and financial aggregates. Most papers in this field investigate this issue by looking at the impact of changes in average temperature levels. For example, Dell et al. (2012), Colacito et al. (2019), and Du et al. (2017) find that rising temperatures negatively affect economic growth. Moreover, Bansal et al. (2016) and Donadelli et al. (2017) show that temperature shocks have a significant negative effect on equity valuations and carry a positive premium in equity markets. Unlike these studies, we do not examine the effects of a rising temperature level but examine the implications of temperature volatility shocks on aggregate productivity, consumption, and equity prices. In this respect, we support Katz and Brown (1992) and Schär et al. (2004) who argue that focusing exclusively on the change in the mean of climate variables may underestimate the overall economic costs of climate change.

Our paper is also connected to the literature on the economics of climate change quantifying the macroeconomic and financial effects of global warming. A popular approach to quantifying the economic costs of climate change and carbon emissions is the use of IAMs (Stern 2007; Nordhaus 2008). Recent contributions in this class of models are provided by Golosov et al. (2014) and Cai et al. (2015) who study climate change within a DSGE framework. Bansal and Ochoa (2011a) and Bansal et al. (2016) account for temperature dynamics in long-run consumption risk models to quantify the effects of temperature shocks on consumption and asset prices. We differ from IAMs as we do not model temperature effects on economic activity as a damage function on the level of GDP, but rather on the growth rate of TFP. We therefore allow temperature to permanently affect economic activity as in the long-run consumption risk models (see Pindyck 2012). Unlike the latter, we model temperature effects in a production economy framework, which allows us to analyze the effects of temperature also on investment and labor growth. Moreover, as opposed to IAMs, we do not compute economic costs as losses in GDP but follow Bansal and Ochoa (2011b) who define welfare costs of temperature risk as in Lucas (1987). We believe our modeling choice to be more natural than others for several reasons. First, it allows for a clear-cut exogenous link between temperature dynamics (i.e., temperature level and temperature volatility) and productivity growth, as observed in the UK macro and weather data. Second, it is not driven by a large number of arbitrary choices. Actually, parameters are calibrated to match main macro-quantities, asset prices and temperature statistics. Third, it accounts for the joint dynamics of temperature level and temperature volatility and equity returns, an aspect not considered in standard IAMs (or any other previous climate change models).

Finally, our theoretical analysis builds on the recent production-based asset pricing literature dealing with the long-run effects of aggregate productivity shocks (Croce 2014) or oil shocks (Hitzemann 2016; Hitzemann and Yaron 2017; Ready 2018) on macroeconomic aggregates and asset prices. Most of the elements of our production economy are therefore as in Croce (2014). What is new in our model is that aggregate productivity is influenced by temperature volatility shocks, as suggested by the empirical evidence. In this respect, we are more closely related to Gao et al. (2016) who develop a two-sector production model to study the effects of oil volatility risk on macroeconomic variables and asset prices.

3 The Facts

This section empirically examines the implications of temperature volatility shocks. First, in Sect. 3.1, we describe the data employed in our analysis and present some preliminary facts. In Sect. 3.2, we analyze the effects of temperature volatility shocks on aggregate macro quantities such as productivity, output, consumption, and investment. For the sake of completeness, Sect. 3.3 compares temperature level and temperature volatility shock effects. A battery of robustness tests on the macroeconomic implications of temperature volatility shocks are presented and discussed in Sect. 3.4. The effect of temperature volatility shocks on asset prices are then presented in Sect. 3.5. We finally examine whether temperature volatility shocks are priced in the cross-section of equity returns in Sect. 3.6.

3.1 Data Description and Some Preliminary Facts

Our empirical analysis on the effects of temperature volatility (hereinafter TVOL) on macroeconomic and financial aggregates is based on annual UK data.. Data on real TFP, output, consumption, investment, and labor force have been retrieved from the “Bank of England’s Three Centuries Macroeconomic Dataset”. All macroeconomic series run from 1900 to 2015, except for TFP which starts in 1800. The equity market return and the risk-free rate have been obtained from the “Barclays Equity Gilt Study 2016”. Data are annual for the period from 1900 to 2015. Monthly temperature levels have been retrieved from MET Office for the period 1659–2015 (http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadcet/). This dataset represents one of the longest continuous temperature records available. Admittedly, MET temperature levels are observed only for central England. However, this does not represent a major drawback. In fact, Croxton et al. (2006) suggest that the central-UK temperature level fits pretty well the average temperature level of the UK as a whole.Footnote 3 Some key statistics on the UK temperature level and volatility and main macro and financial variables are reported in “Appendix 1” (see Table 13). Two results are noteworthy: (1) the UK annual average temperature rose by more than 1 degree Celsius over the last two centuries and (2) temperature volatility rose as well and exhibited an unprecedented increase in the last 15 years.

In the spirit of Katz and Brown (1992) and Schär et al. (2004), we capture changes in climate conditions by means of shifts in TVOL. Precisely, we rely on a temperature anomaly volatility index, defined as the difference between the intra-annual volatility and a benchmark volatility level. The latter is represented by the average intra-annual volatility calculated over the pre-industrial revolution era in the UK (i.e., 1659–1759). Note that both positive and negative deviations from the benchmark can have adverse economic effects. It has been shown that a relatively high level of TVOL tends to be associated with more frequent extreme weather events (see, for example, Elagib 2010; Ito et al. 2013; Brown and Lall 2006). On the other hand, a year with relative low variation across monthly temperatures—caused, for instance, by a persistent summertime heatwave—could result in severe droughts and flow of surface waters. As a consequence, crop and hydroelectricity production drop and irrigation is largely reduced. In addition, substantial weather fluctuations (positive or negative) may affect people’s mood leading to changes in consumption dynamics (Spies et al. 1997; Murray et al. 2010) and portfolio investment decisions (Kamstra et al. 2003; Cao and Wei 2005). Our TVOL measure is thus defined as follows:

where \(\sigma _{(JAN-DEC)_{t}}\) indicates intra-annual volatility in year t (i.e., the standard deviation computed using monthly temperature levels within each year in the post-industrial revolution era), and \(\bar{\sigma }_{(JAN-DEC)_{1659-1759}}\) represents the average intra-annual volatility observed over the industrial revolution era (i.e., 1659–1759).

Climate change is expected to increase the frequency of extreme weather events. Of course, linking any single weather event to global warming can be complicated. However, volatility in main climate drivers (especially in temperature and rainfall) seems to be more strongly related to the frequency of severe weather events. This is confirmed by Fig. 1 (Panel A) which shows (historically) a positive correlation between TVOL and the number of extreme weather events.Footnote 4 Importantly, this positive relationship has strengthened (on average) in the post-war period and skyrocketed in the last 20 years. In addition, TVOL is found to be negatively correlated with consumption growth (Fig. 1, Panel B) and aggregate equity market returns (Fig. 1, Panel C). In both cases, the negative relationship is stronger for the period 1950–2015 than for the pre-war period (i.e., 1900–1950). These dynamics confirm an increasing degree of co-movement between climate change-related uncertainty and economic quantities, and could be responsible for increasing adaptation costs (or slower adaptation).

Temperature dynamics and extreme weather events, 1900–2015. Notes: Panel A depicts the dynamics of the UK intra-annual temperature volatility (black line, 5Y average) and the annual average number of weather extreme events (dotted gray line, 5y average). Annual number of extreme events \(:=\) number of extreme rainfalls, floods, frosts, hot temperature anomaly, and droughts occurred within a year in the UK for the period 1900–2015. The number of extreme events is constructed using the chronological listing of events reported in the website http://www.trevorharley.com/weather_web_pages/britweather_years.html. Panel B plots the dynamics of the UK intra-annual temperature volatility (black line, 5Y average) and consumption growth (dotted gray line, 5y average). Panel C presents the dynamics of the UK intra-annual temperature volatility (black line, 5Y average) and the stock market returns (dotted gray line, 5y average). The dotted vertical line (in all plots) indicates the year 1950

3.2 Temperature Volatility Shocks and the UK Macroeconomy

To test for the sign and the direction of the TVOL–TFP nexus over time, we perform a Granger causality test (GC) between TFP growth (\(\varDelta a\)) and TVOL for three different sample periods: (1) 1800–1900; (2) 1900–1950 and (3) 1950–2015. This allows us to account for the fact that both climate change-related phenomena and the structure of the UK economy have changed substantially over the last two centuries. In order to improve the size and power of the test, a residual-based bootstrap technique is employed. Entries in Table 1 suggest the presence of a time-varying component in the sign of the causality between TFP growth and TVOL.

A significant unidirectional causality from TVOL to TFP is observed in the pre- and post-war periods. However, the sign of the causality differs across the two periods. Actually, it is positive (negative) for the period 1900–1950 (1950–2015). We instead find no evidence of a statistical significant causality between TVOL and productivity in the 19th century. All entries in Table 1 may seem surprising as one would expect negative implications for TFP growth following rising temperature levels variability in particular during those periods in which production relies largely on the agricultural sector, which is well known to be more influenced by climate change (Dell et al. 2012).Footnote 5

We suspect that during the period 1900–1950, workers in the agricultural sector were forced to adapt and invest in technology in order to reduce the economy’s vulnerability to extreme weather events. This could explain the positive and statistically significant sign in the causality from TVOL to TFP growth. In contrast, the past 60 years are characterized by negative economic effects. It is widely accepted that within this period the services-related sectors have contributed most to economic growth in developed countries. As discussed in Tol et al. (2000), these sectors tend to be less influenced by climate change-related phenomena. It is thus most likely that these sectors allocated most of their resources in technologies for the purpose of increasing productivity and not adapting to climate change. However, when extreme whether-related events such as flood and storms—induced by drastic changes in temperature dynamics—occur, the economy as a whole is affected.Footnote 6 In other words, it is most likely that natural disasters will generate more sizable adverse effects in an economy characterized by highly-productive sectors than in agricultural-based economies. Note also that the period 1950–2015 is characterized by a higher number of extreme weather events than the pre-war period (see Fig. 1, Panel A). Even in the presence of a relatively high level of technology, massive variations in temperature levels (within the year and across years) leading to more frequent extreme weather events could seriously harm any form of investment to climate change adaptation. In particular, more volatile weather conditions make (1) firms less willing to invest in adaptation due to higher cost and (2) existing adaption mechanisms weaker and slower.

To quantify the impact of time-varying temperature uncertainty, we compute the impulse response of future TFP growth to a one-standard deviation shock in TVOL.Footnote 7 The analysis follows the same strategy as the GC analysis and is thus carried out for the following sub-periods: 1800–1900, 1900–1950, and 1950–2015. Impulse responses (dashed grey lines)—obtained from a bi-variate VAR of TVOL and TFP growth—are depicted in Fig. 2. It is worth noting that the impact of a TVOL shock on TFP is not constant over time. Over the period 1800–1900, the effect of a positive shock in TVOL on productivity growth oscillates around zero. The period 1900–1950 is instead characterized by a positive impact of TFP growth following a TVOL shock: on impact the response of productivity is slightly negative and becomes positive and statistically significant after two periods. In line with the evidence provided by our preliminary GC analysis, the nature of the TVOL–TFP nexus has changed in the post-war era. In particular, a rise in TVOL is found to be detrimental for TFP growth. Importantly, this negative effect is statistically significant and lasts for almost 4 years (Fig. 2, Panel C).

Impulse response of TFP to temperature volatility. Notes: This figure depicts the generalized impulse response of TFP growth (\(\varDelta a\)) to a one-standard-deviation shock in temperature volatility (TVOL). Impulse responses are obtained by estimating a bi-variate VAR(1) using data for three different periods: (1) 1800–1900 (PANEL A); (2) 1900–1950 (PANEL B); and (3) 1950–2015 (PANEL C). VAR estimations include a constant. Solid “black” lines: IRFs. Dashed “dark grey” lines: 90% confidence bands. Dashed “light grey” lines: 68% confidence bands

In order to get a better understanding of the effects of an increase in our TVOL index on real economic activity, we also compute impulse responses of consumption, output, investment, employment and TFP growth to a TVOL shock. Given the absence of theories linking temperature volatility and macroeconomic aggregates, we do not rely on any specific identification scheme and compute generalized impulse responses that do not depend on the ordering of variables in the system. Impulse responses of main macro-aggregates obtained from our augmented VAR are reported in Fig. 3 for the sub-period 1900–1950 and in Fig. 4 for the post-war period. First, and most importantly, we find that the inclusion of additional macroeconomic variables does not alter the impact of the TVOL shock on TFP growth. As in Fig. 2 (Panel B), over the period 1900–1950, TFP growth displays an immediate small and statistically insignificant drop, with a fast subsequent recovery and rebound from 2 years after the shock. Differently, a TVOL shock produces a statistically significant drop in the TFP of around 0.4pp in the post-war period. In line with our preliminary bi-variate estimations (see Fig. 2, Panel C), this adverse effect lasts for (approx.) 4 years. Impulse responses on the other macroeconomic aggregates also differ across sub-periods. For the period 1900–1950, we observe a drop in consumption and investment (Fig. 3, Panels C and D). Instead, labor and output increase on impact (Fig. 3, Panels B and E). However, most of these effects are not statistically significant. Over the post-war period, labor, consumption and output react differently to a TVOL shock. For instance, the impact on labor growth is negative and lasts for several years. However, it is not statistically significant (Fig. 4, Panel B). Output increases on impact and displays a significant drop (at 32%) 2 and 3 years after the shock (Fig. 4, Panel E). Consumption displays a similar (but less significant) response. Overall, our empirical findings suggests that in the post-war era TVOL shocks generate non-negligible adverse effects on real economic activity.Footnote 8

Impulse response of macroeconomic variables to temperature volatility (1900–1950). Notes: This figure depicts generalized impulse responses of TFP growth (\(\varDelta a\)), labor growth (\(\varDelta L\)), consumption growth (\(\varDelta C\)), investment growth (\(\varDelta I\)), and output growth (\(\varDelta Y\)) to a one-standard-deviation shock in temperature volatility (TVOL). VAR is estimated with one lag and a constant. Solid “black” lines: IRFs. Dashed “dark grey” lines: 90% confidence bands. Dashed “light grey” lines: 68% confidence bands

Impulse response of macroeconomic variables to temperature volatility (1950–2015). Notes: This figure depicts generalized impulse responses of TFP growth (\(\varDelta a\)), labor growth (\(\varDelta L\)), consumption growth (\(\varDelta C\)), investment growth (\(\varDelta I\)), and output growth (\(\varDelta Y\)) to a one-standard-deviation shock in temperature volatility (TVOL). VAR is estimated with one lag and a constant. Solid “black” lines: IRFs. Dashed “dark grey” lines: 90% confidence bands. Dashed “light grey” lines: 68% confidence bands

3.3 Temperature Volatility and Temperature Level Shocks

Results presented so far have focused exclusively on the role of TVOL shocks. What about temperature level shocks? Are results still valid once accounting for temperature level dynamics? To address these issues, we need to investigate whether the negative effect of a TVOL shock on TFP growth observed over the period 1950–2015 is driven by shifts in the UK temperature level. We therefore estimate a VAR(1) including TFP growth, the average temperature level and temperature volatility. Impulse responses from this test are depicted in Fig. 5 and suggest that the adverse effect of a TVOL shock on the TFP growth is not absorbed by temperature level shifts. Surprisingly, the TVOL-induced negative effect on TFP growth (Panel B) is more statistically significant than the one induced by a temperature level shock. Note also that our robustness check corroborates recent empirical findings—based mainly on U.S. data—showing that shifts in temperature levels undermine real economic activity (Dell et al. 2012; Colacito et al. 2019; Bansal et al. 2016; Du et al. 2017; Donadelli et al. 2017).

Impulse response of TFP to temperature (T) and temperature volatility (TVOL). Notes: This figure depicts the generalized impulse response of TFP growth (\(\varDelta a\)) to a temperature (Panel A) and temperature volatility (Panel B) shock. Impulse responses are obtained by estimating a VAR (with one lag) including a temperature anomaly index (T), our measure of temperature volatility (TVOL) and TFP growth. A constant is included. In line with climate change studies, temperature anomaly index is calculated as deviations of yearly average temperature from pre-industrial revolution temperature mean (1659–1759). Solid “black” lines: IRFs. Dashed “dark grey” lines: 90% confidence bands. Dashed “light grey” lines: 68% confidence bands

3.4 Robustness

We consider various robustness checks regarding the effect of TVOL shocks on TFP growth and other macroeconomic aggregates.

First, we compute impulse responses using a different identification scheme. By relying on a simple Cholesky decomposition where TVOL is ordered first, we show that a TVOL shock produces qualitatively and quantitatively similar impulse responses (see Fig. 12).

In a second check, we ask whether alternative VAR models provide similar responses of TFP growth and other macroeconomic variables to a TVOL shock. In practice, we compute impulse responses using a different lag order (i.e., VAR(2)), the local-projection methodology suggested by Jordà (2005), and a Bayesian VAR (BVAR). The impulse responses estimated from these different VAR models and for the periods 1900–1950 and 1950–2015 are reported in “Appendix 2”. The pattern of the response of TFP growth to a TVOL shock seems to be robust to alternative VAR specifications. Actually, the dynamics depicted in Fig. 13 are similar to those obtained from our benchmark bi-variate VAR (see Fig. 2). Similar conclusions can be drawn by comparing Figs. 14 and 15 to Figs. 3 and 4.

Third, in order to further investigate the time-varying nature of the impact of TFP growth to TVOL shocks, we compute the dynamics of the impulse response of TFP growth to a shock in TVOL by estimating a Bayesian VAR in a rolling-window fashion. Using a window length of 50 years, we corroborate our previous findings suggesting that the negative impact of TVOL on productivity materializes in the post-war period (see Fig. 17). More importantly, our rolling window estimates show that the magnitude of the negative impact of TVOL shocks on the TFP is increasing over time. For the sake of robustness, we compute the dynamic impulse response of TFP growth to TVOL shocks by employing a full-fledged time-varying parameter vector autoregressive (TVP-VAR) a l Primiceri (2005). Impulse responses are estimated by relying on a VAR including our measure of temperature volatility, the annual average temperature level and the TFP growth. By using data for the period 1700–2015, we observe a negative impact of TVOL on TFP growth only starting from the second half of the 20th century (see Fig. 17, Panel C). We argue that such evidence can be also related to an increasing degree of urbanization. Intuitively, damages caused by extreme weather events are supposed to be larger in the presence of a relatively high degree of urbanization. For instance, in Western Europe the degree of urbanization rose massively in the post-war period. Actually, it was around 40% at the beginning of the 20th century and jumped to almost 80% in early ’00s (Source: OWID). More importantly, over the last 50 years the UK has registered an average urbanization rate of 80%. In addition, as previously mentioned, the structure of national product in the UK has undergone drastic changes over the years (Deane 1957). Actually, the contribution of the agriculture, forestry and fishing (manufacturing, mining, construction and services) sector has showed a declining (increasing) path. Once again, the idea here is that the adverse effects of climate change materialize in environments exhibiting a high degree of urbanization/industrialization and in those economies whose national industrial profile is dominated by services sectors (e.g., finance, tourism, ICT).

Fourth, we consider a different proxy for temperature volatility. Specifically, we rely on an inter-annual measure of temperature volatility. This is captured by computing the standard deviation of annual average temperature levels using a rolling window of 10 (or 15) years. Bi-variate VAR estimates suggest that an inter-annual temperature volatility shock has a negative effect on productivity (see Fig. 18). Note that this is in line with results from our benchmark analysis (Fig. 2, Panel C) where TVOL is defined as in Eq. (1). However, the effect is weaker in statistical terms but more long-lasting.

Finally, in attempting to further capture the effect of climate change variability on real economic activity, we estimate a bi-variate VAR using a different climate variable. Specifically, we build a Rainfall Volatility Index for the UK and estimate its impact on TFP growth. Similarly to the volatility of temperature, rainfall volatility is found to undermine aggregate productivity growth only in the post-war era. However, the impact is less statistically significant and (slightly) less persistent (see Fig. 19).

Taken together, our empirical findings suggest that the nature of the effects of TVOL on TFP growth in not constant over time. In particular, TVOL is found to positively (negatively) affect TFP growth over the pre-war (post-war) period. Data for the period 1950–2015 also suggest that TVOL shocks adversely affect the growth rate of output, investments, and consumption. This evidence might be the result of firms’ inattention to the potential effects of climate change on the technology stock in the manufacturing and services sectors. To examine whether these climate change-related effects are also reflected in the dynamics of financial variables, we move to study the relationship between TVOL and asset prices in the next section.

3.5 Temperature Volatility Shocks and Financial Variables

In the spirit of the most recent macro-finance literature focusing on the effects of climate change, we also examine whether shocks in temperature volatility affect asset prices (Bansal and Ochoa 2011a, b; Bansal et al. 2016). To this end we run a VAR with three variables including our measure of temperature volatility, the equity market return (R), and the risk-free rate (\(R_{f}\)). In doing so, we also check whether the previously obtained response of TFP growth to TVOL is robust to the inclusion of these additional variables. Note that such variables can also be responsible for shifts in productivity growth (Croce 2014).

Based on data availability, impulse responses are presented for two sub-samples: (1) 1900–1950 (Fig. 6) and (2) 1950–2015 (Fig. 7). For the period 1900–1950, we find that the response of both the risk-free rate (Fig. 6, Panel A) and the equity return (Fig. 6, Panel B) to a TVOL shock is negative. However, these two effects are not statistically significant. Similar effects are found for the period 1950–2015, but differently from the results of the pre-war period, we find that the effect of a TVOL shock on the equity return is immediate and highly statistically significant (Fig. 7, Panel B). In “Appendix 2” we also show that this pattern is robust with respect to different VAR model specifications (Fig. 16, Panel B).

Impulse response of financial variables to temperature volatility (1900–1950). This figure depicts generalized impulse responses of the risk-free rate (\(R_{f}\)) and the equity market return (R) to a one-standard-deviation shock in temperature volatility (TVOL). VAR is estimated with one lag and a constant. Solid “black” lines: IRFs. Dashed “dark grey” lines: 90% confidence bands. Dashed “light grey” lines: 68% confidence bands

Impulse response of financial variables to temperature volatility (1950–2015). Notes: This figure depicts generalized impulse responses of risk-free rate (\(R_{f}\)) and equity market return (R) to a one-standard-deviation in temperature volatility (TVOL) shock. VAR is estimated with one lag and a constant. Solid “black” lines: IRFs. Dashed “dark grey” lines: 90% confidence bands. Dashed “light grey” lines: 68% confidence bands

Finally, for the sake of robustness, we compute IRFs also from a VAR including TVOL, \(\varDelta a,\) and R. The idea here is to investigate whether the two main transmission channels through which TVOL shocks affect the economy do not vanish when they are jointly considered. Figure 20 shows that the effect of a TVOL shock is negative and statistically significant for productivity (Panel A) and the equity return (Panel B) over the post-war period. This indicates that the TFP and the equity return represent important transmission channels of temperature volatility shocks on the UK economy.

3.6 Temperature Volatility Shocks and the Cross-Section of Returns

In this paper we are not only interested in the implications of TVOL shocks for the macroeconomy but also in their effect on asset prices and in particular on the cross-section of stock returns. Our interest in the asset pricing implications of TVOL risk is also motivated by recent empirical evidence about the effects of temperature shifts on asset prices. Using US data, for instance, Balvers et al. (2017) find that temperature shocks have a negative impact on equity market returns. Temperature shocks are also found to have a positive impact on the cost of capital. The magnitude of this impact is increasing over time. Using panel data on 39 countries, Bansal et al. (2016) show that temperature risks have a significant negative impact on equity valuations. Bansal and Ochoa (2011a) find that temperature risk is priced in the cross-section of portfolio equity returns. In particular, their cross-sectional tests indicate temperature-related risks to be responsible for a positive risk premium. Moreover, the risk premium arising from temperature-related risks tends to be larger in countries closer to the equator than in those further away from it.

We contribute to this literature by examining the implications of temperature volatility shocks for the cross-section of UK (and EU) stock returns. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study to investigate whether TVOL shocks carry a risk premium and if so, of which sign. We fill this gap by means of standard cross-sectional regressions of stock returns. In our framework average returns are a function of the newly introduced climate driver, namely TVOL innovation. In the spirit of Bansal et al. (2016) and Garlappi and Song (2017), when estimating temperature volatility risk premia, we control for market and productivity risks. In this respect, we let portfolio returns be a function of the excess return of the market portfolio, \(R_{M}^{e}\), and the 2-year moving-average of aggregate productivity growth, \(\varDelta a\).Footnote 9 The following factor model is thus estimated:

where \(R^{i}\) is the return of asset i, \(\beta _{i} =[\beta _{mkt, i}, \beta _{\varDelta a, i}, \beta _{\varDelta TVOL, i}]\) is the vector of risk exposures of asset i containing the exposures of stock returns to the market, variations in macro-economic growth and innovations to temperature volatility. Finally, \(\lambda =[\lambda _{MKT}, \lambda _{\varDelta a}, \lambda _{\varDelta TVOL}]\) are the implied factor risk premia which encompass both the vector of the underlying prices of risks and the quantity of risks. The classical two-stage regression approach is followed. Therefore, in the first stage, we estimate the exposure to the above risk factors (i.e., the betas) from full-sample time series regressions:

The vector of risk premia is estimated from the cross-sectional second stage regression:

where \(\mathbb {E}[R^{i}]\) is the average return of each asset over time and the vector of estimated betas

for each portfolio is taken from the first stage regression (3).Footnote 10 We refer to this approach as “Avg Returns”.

An alternative second stage regression is suggested by Fama and MacBeth (1973). Here, the second step consists of computing T cross-sectional regressions of the returns on the betas estimated from the first step. Formally,

The estimated \(\lambda \) is then computed by averaging the \(\lambda \)s over T. This alternative “Fama-McBeth” procedure gives exactly the same values for \(\lambda \), but different standard errors.

In our benchmark tests, we use UK portfolios formed on different characteristics provided in Stefano Marmi’s Data Library following the methodology outlined in Fama and French (1993).Footnote 11 We first use six portfolios formed on size and book-to-market and six portfolios formed on size and momentum, a total of twelve portfolios. We then use 40 portfolios formed on the following characteristics: price-earnings, price to book, price to cash flow and gross profit margin. All these portfolios are available for the period 1989–2011.

Table 2 reports the risk premium estimates from the second stage for the twelve UK benchmark portfolios. Results are reported for both the univariate model where only temperature volatility risk is considered (specification “1”) and the multivariate model accounting for market and macroeconomic risk (specification “2”). The risk premium estimates from TVOL shocks are positive and statistically significant. Results are similar after controlling for market and macroeconomic (TFP) risk. Similar conclusions can be drawn by looking at Table 3 which reports risk premia estimated by employing the 40 UK portfolios. In this larger set of portfolios, the temperature volatility related risk premium is still found to be positive but smaller. Moreover, results are less statistically significant when the “Fama-McBeth” approach is used (Table 3, Panel B).Footnote 12

To get additional insights on the effect of temperature volatility shocks on the cross-section of stock returns, in an alternative test we use a larger number of portfolios. Precisely, we use 100 EU portfolios: 25 portfolios formed on size and book-to-market; 25 portfolios formed on size and operating profitability; 25 portfolios formed on size and investment; and 25 portfolios formed on size and momentum. Data on these EU portfolios are freely available from Kenneth R. French’s Data Library for the period 1990–2015. Results from this alternative test are reported in Table 4. The result with respect to temperature volatility shocks are qualitatively similar to those reported in Tables 2 and 3.

Finally, for the sake of robustness, we perform our cross-sectional tests by controlling for the 2008–2009 Great Recession. We first run our one factor regression by focusing on the pre-2008 period. Second, in order to control for the crisis years we run a four factors regression where a dummy capturing the 2008 and 2009 is added. Results are qualitatively similar and are reported in “Appendix 3” (see Tables 14 and 15).

Note that the evidence that TVOL risk demands a positive risk premium in the cross-section of stock market returns—even after controlling for market and macroeconomic risk—corroborates the findings in Sect. 3.5. In Sect. 3.5 we find that TVOL shocks significantly affect financial variables. Given that our empirical analysis predicts significant adverse effects of temperature volatility on asset prices and macroeconomic variables for the post-war period, we rationalize these findings in a production economy featuring temperature volatility risk (i.e., TVOL shocks). This allow us to quantify the economic costs of this type of risk.

4 A Framework to Examine the Macro-Effects of TVOL Shocks

We rationalize our empirical findings within a production economy featuring long-run macro risk à la Croce (2014) and temperature risk along the lines of Bansal and Ochoa (2011a) and Donadelli et al. (2017). As a main novel ingredient, we introduce stochastic uncertainty of temperature into the model (i.e., TVOL risk). Specifically, temperature dynamics are coupled with the evolution of TFP in a way that innovations in temperature volatility generate a negative impact on long-run productivity. In a robustness test, we also introduce a stochastic depreciation rate of capital to provide new insights on the interplay of capital accumulation and climate change. Note that our main goal here is to maximize the intuition and insight into the relationships between TVOL risk and the macroeconomy and asset prices, and avoid tangential complications. We therefore strive to keep the model as simple as possible while still matching main macro-quantities and asset prices. For this reason, we deliberately introduce real rigidities into the model only in the form of capital adjustment costs and abstract from any other type of frictions (e.g., financial and labor market frictions).Footnote 13

Let us stress that our choice of focusing on a production economy with long-run productivity risk (i.e., a RBC model where productivity growth contains a small persistent component) is motivated by its ability to account for asset pricing anomalies while preserving main RBC features. Specifically, the model generates a low and smooth risk-free rate as well as a sizable excess return on the aggregate stock market of around 3.0%. Using a standard New-Keynesian monetary model would not allow to simultaneously match main macro-quantities and asset prices, unless doubts and ambiguity aversion are accounted for (Benigno and Paciello 2014).

Temperature and Productivity: We capture the economic effects of temperature volatility shocks by using the following specification for productivity and temperature dynamics:

where the shocks \(\epsilon _{a,t+1}\), \(\epsilon _{x,t}\), \(\epsilon _{\theta ,t+1}\) and \(\epsilon _{z,t+1}\) are independent of each other and are each distributed i.i.d. standard normally. In addition to temperature level shocks \(\epsilon _{z,t}\), we introduce shocks to the volatility of temperature \(\epsilon _{\theta ,t}\).Footnote 14 The unconditional expected growth rate of productivity is \(\mu _a\). The parameter \(\mu _{z}\) captures the long-run average temperature level. In this economy, short-run productivity shocks are induced by \(\epsilon _{a,t}\), whereas \(\epsilon _{x,t}\), \(\epsilon _{\theta ,t}\), and \(\epsilon _{z,t}\) indicate long-run shocks affecting the persistent stochastic components in productivity growth \(x_t\) and \(x^z_t\). The persistence of long-run macro and temperature-related productivity shocks is measured by \(\rho _x\) and \(\rho ^z_x\), respectively. We specify two distinct long-run components for macro and temperature shocks in order to disentangle the timing of those innovations. In contrast to long-run macro shocks, temperature-related shocks contemporaneously impact TFP growth, as observed in the data.

In line with our empirical findings (see Fig. 5), the shock terms \(\tau _z \sigma _z \epsilon _{z,t+1}\) (\(\tau _\theta \sigma _\theta \epsilon _{\theta ,t+1}\)) represent the impact of changes in the temperature level (temperature volatility) on TFP growth.Footnote 15\(\sigma _z \epsilon _{z,t+1}\) is the unpredictable part of the change in temperature level, while the term \(e^{\theta _{t+1}}\) represents time-varying volatility of temperature. In this setup, \(\theta \) represents a proxy for the volatility of key climate variables (in our case temperature volatility as defined in Eq. (1)). The parameters \(\tau _z\) and \(\tau _{\theta }\) in the dynamics for \(x^z\) in the system (6) capture the direction and the intensity with which unpredictable temperature level and temperature volatility shocks impact long-run productivity growth. Based on the empirical analysis in Sect. 3.2, we assume \(\tau _{\theta } < 0\) when studying the quantitative implications of the model, i.e., TVOL shocks have a negative impact on long-run expected productivity growth. For completeness and to be consistent with our UK-based empirical evidence, we also let the model replicate the negative effect of a shock in the level of temperature on productivity. We thus impose \(\tau _z < 0\). This is also in line with recent studies showing that temperature level shocks harm real economic activity (see, among others, Bansal and Ochoa 2011b; Colacito et al. 2019; Du et al. 2017). Our goal here is to study exclusively the quantitative implications of TVOL risk. We therefore abstract from studying the effects of temperature level shocks on the UK macroeconomy.Footnote 16

Households: The representative household is equipped with recursive preferences, as in Epstein and Zin (1989):

\(\tilde{C}_t\) is a Cobb-Douglas aggregator for consumption \(C_t\) and leisure \(1-L_t\) (the remainder of a total time budget of 1, when the amount of labor is \(L_t\)):

where \(A_t\) denotes aggregate productivity (i.e., TFP).

The stochastic discount factor (SDF) reads:

Firms: The production sector admits a representative, perfectly competitive firm utilyzing capital and labor to produce the output. The production technology is given by

where \(\alpha \) is the capital share and labor \(L_t\) is supplied by the household. The aggregate productivity growth rate, \(\varDelta a_{t} =\log \left( A_{t}/A_{t-1}\right) \), has a standard long-run macro risk component and is subject to temperature and temperature volatility risk, as described in Eq. (6).

The capital stock evolves according to

where \(\delta _K\) is the depreciation rate of capital. \(G(\cdot )\), the function transforming investment into new capital, features convex adjustment costs as in Jermann (1998):

Asset Prices: The intertemporal Euler conditions defining the risk-free rate \(R_t^f\) and the return on capital \(R_t\) are as follows:

where

The price of capital \(q_t\) is equal to the marginal rate of transformation between new capital and consumption:

Given the risk-free rate \(R_t^f = \frac{1}{{\mathbb {E}}_t[M_{t,t+1}]}\) we calculate the unlevered equity risk premium as

Labor Market: In the absence of labor market frictions, optimal labor allocation implies that the marginal rate of substitution between consumption and leisure equals the marginal product of labor:

Market Clearing: Goods market clearing implies that

The model is solved numerically by a second-order approximation using perturbation methods as provided by the dynare++ package.

5 Quantitative Analysis

5.1 Calibration

Our benchmark model is calibrated to an annual frequency and requires us to specify nineteen parameters: four for preferences, three relating to the final goods production technology and labor market, four describing the TFP process, and eight for the dynamics of the UK temperature (see Table 5).Footnote 17 The model is calibrated to match the adverse climate effects on macro-quantities and asset prices observed in the post-war period.

Let us first discuss the “less standard”, i.e., UK temperature-related parameters. The persistence of the innovations in the long-run temperature risk component is chosen to let the model reproduce the relative persistent effect of TVOL shocks on productivity growth observed in the postwar UK temperature and macro data (Fig. 2, Panel C). To this end, we set \(\rho ^x_z\) = 0.6. Note that this value is in line with the average empirical estimates reported in Fig. 8 where we estimate the dynamics of \(\rho ^x_z\) using a rolling window of 50 years.Footnote 18

Speed of adaptation. Notes: This figure shows the evolution of the parameter \(\rho ^z_x\) representing the persistence of temperature-related TFP shocks. \(\rho ^z_x\) is estimated from the system in Eq. (6)—in a state space framework—using a rolling window of 50 years for the period 1900–2015. Var–Cov matrix is estimated using Huber–White standard errors

The two parameters measuring the sensitivity of TFP growth to temperature-related shocks are jointly calibrated using the empirical evidence provided in Sect. 3.3. Therefore, the parameter \(\tau _\theta \) that measures the impact of TVOL shocks on TFP growth is calibrated to a value of \(-\,0.0285\). This implies that in the model productivity growth falls by 0.4pp following a one-standard deviation temperature volatility shock (see Fig. 5, Panel B). The parameter \(\tau _z\), measuring the impact of temperature level shocks on TFP growth, is then calibrated to a value of \(-\,0.0054\), which implies in our model that productivity growth declines by around 0.3pp after an unexpected one-standard deviation increase in temperature (see Fig. 5, Panel A). Regarding the stochastic volatility parameters in the temperature process, we set the persistence of TVOL shocks equal to 0.85, as suggested by empirical estimates. The standard deviation of time-varying temperature uncertainty, \(\sigma _\theta \), is assumed to be a small fraction of the volatility of temperature level shocks. Precisely, we impose \(0.25 \cdot \sigma _z\).Footnote 19 The other parameters regarding temperature dynamics are set to match the UK temperature statistics observed in the data over the period 1950–2015. In particular, we set \(\mu _{z} = 9.74\) (degrees Celsius), \(\rho _{z} = 0.4\), and \(\sigma _z = 0.56\) to match the long-term mean, persistence and volatility of UK temperature, respectively.

We next turn to the standard parameters. Most of the parameters are set in accordance with the long-run risk literature and are chosen to match the main dynamics of UK macroeconomic quantities and prices. More precisely, as in Croce (2014), we set the coefficient of relative risk aversion, \(\gamma \), and the elasticity of intertemporal substitution (IES), \(\psi \), to values of 10 and 2, respectively (i.e., the representative agent has preference for the early resolution of uncertainty, since \(\gamma >\psi ^{-1}\)). In line with Bansal and Ochoa (2011b), the annualized subjective discount factor, \(\beta \), is fixed at 0.988. The consumption share in the utility bundle \(\tilde{C}\) is chosen such that the steady-state supply of labor is one third of the total time endowment of the household. Given the other parameters, this is achieved by setting \(\nu \) = 0.3407. On the final production side, we set the capital share \(\alpha \) in the production technology equal to 0.345 as in Croce (2014). Regarding the adjustment cost parameters, \(\tau \) is set to 0.7 as in Kung and Schmid (2015). The constants \(\alpha _1\) and \(\alpha _2\) are chosen such that there are no adjustment costs in the deterministic steady state. The depreciation rate of capital \(\delta _K\) is set to 0.06 as in Croce (2014). The parameter \(\mu _{a}\) is set to a value of 0.0142, so that the average annual TFP growth rate is 1.42%, as indicated by the UK data. The volatility of the short-run shock, \(\sigma _a\), is calibrated to match the annual volatility of output growth observed in the macroeconomic data. We then calibrate the parameters of the long-run productivity risk process, \(x_t\), according to empirical estimates, resulting in \(\rho _x=0.97\) and \(\sigma _x = 0.12 \sigma _a\).Footnote 20

5.2 Macro and Asset Pricing Implications

The main results produced by our benchmark calibration (BC) are reported in Table 6, denoted by specification [1]. In line with standard long-run risk models, our framework produces \({\mathbb {E}}[R_{ex}^{LEV}]= 3.14\%\), a value close to what is observed on the major capital markets around the world. Compared to specification [2], representing a model without temperature volatility effects, we observe that the impact of TVOL on TFP growth significantly affects asset prices. \({\mathbb {E}}[R_{ex}^{LEV}]\) increases by 11 basis points when volatility effects of temperature are introduced.

Equity volatility also experiences an additional increase by 15 basis points after introducing temperature volatility effects. The correlation between the excess return and temperature volatility is negative with a value of \(-\,0.13\). The reason for the negative sign is that unexpected increases in TVOL negatively affect firms’ productivity and, hence, their return on capital. In the data, the negative correlation is somewhat stronger than in our benchmark model.

The negative effects of a rise in TVOL on the macroeconomy are captured by a negative correlation between the volatility of temperature and both TFP and output growth, with values of \(-\,0.19\) and \(-\,0.16\), respectively. An important advantage of our model is that the inclusion of temperature volatility risk can explain asset price dynamics and replicate TVOL effects in the data, while it does not affect the long-run moments of macroeconomic quantities.

To analyze how TVOL shocks are transmitted through the economy, we plot the responses of macro quantities to an unexpected increase in TVOL (see Fig. 9). This shock negatively affects the temperature-related long-run risk component of productivity growth. While long-run macro shocks have an delayed effect on productivity, an unexpected temperature volatility increase reduces TFP growth on impact by about 0.4pp. This translates into an immediate decrease in consumption growth of more than 0.2pp (Panel B) and a decrease in investment of more than 0.4pp, which reduces total output growth by almost 0.3pp (Panel C).

Response of macro quantities to temperature volatility. This figure reports impulse responses (expressed as percentage annual log-deviations from the steady state) for a length of 10 years of TFP growth, \(\varDelta a\), consumption growth, \(\varDelta c\), output growth, \(\varDelta y\), investment growth, \(\varDelta i\), labor growth, \(\varDelta l\), and labor productivity growth, \(\varDelta lp\), with respect to a TVOL shock. Solid black lines: model-implied impulse responses. Dashed black lines: average empirical impulse responses (i.e., average of the three different VAR models impulse responses estimated and plotted in Fig. 15). All the parameters are calibrated to the values reported in Table 5

Our production economy model further allows us to analyze the impact of TVOL shocks on labor market dynamics. While the effect on labor growth is negative during the first two periods, it becomes positive afterwards due to the income effect. As the agent feels poorer, she reduces consumption of leisure and increases labor supply. Labor productivity growth falls on impact as well, since labor growth decreases less than output growth. Later on, the effect is still negative since labor growth turns positive, while output growth is still negative over a longer horizon. Thus, our model reproduces the negative effects of a temperature volatility shock on macroeconomic quantities found in Fig. 4 with a magnitude close to the empirical counterparts. So, modeling temperature volatility shocks within a production economy with endogenous investment and labor decisions represents the most natural choice.

As indicated by our VAR analysis, TVOL shocks also affect the financial sector. Impulse responses for financial variables are shown in Fig. 10. As unexpected increases in TVOL reduce productivity, firms’ profits decline, which also has a negative effect on dividends. Due to the fall in investment, the price of capital depreciates, which implies lower stock market returns (Panel B) and a contemporaneous increase in the stochastic discount factor (Panel E). The price dividend-ratio increases following the shock (Panel D) because dividends decrease more than equity prices in our model. As equity markets experience a contraction, the agent’s demand for risk-less securities increases, producing a drop in the risk-free rate (Panel A). As the returns on the aggregate stock market decreases more than the risk-free rate, the excess return declines as well (Panel C). This also means that the equity market does not provide insurance against temperature volatility risk. There is no positive excess return when the marginal utility of the agent is high, i.e. in a bad state of the world. Therefore, temperature volatility risk is associated with increases in the equity premium (see Table 6).

Responses of asset prices to temperature volatility. Notes: This figure reports impulse responses (expressed as percentage annual log-deviations from the steady state) for a length of 10 years of the log of the price dividend ratio, log(p/d), the pricing kernel, SDF, the equity market return, \(R_{m}\), the risk-free rate, \(R_{f}\), and the excess return, \(R_{ex}\), with respect to a TVOL shock. All the parameters are calibrated to the values reported in Table 5

Correlated Long-Run Macro and Temperature Volatility Shocks: To capture possible adaptation to temperature volatility risk, we assume long-run TFP shocks and TVOL shocks to be positively correlated. This may reflect increasing investment by agents in new technologies to shield against higher temperature volatility, and this investment increases productivity. In specification [3], we therefore set \(\rho (\epsilon _x,\epsilon _{\theta })=0.5\). The counter-cyclicality between the equity market return and temperature volatility, i.e. \(\rho (\theta ,R_{ex}^{LEV})<0\), almost disappears, which decreases the overall level of risk. As a result, the equity risk premium decreases by about 59 basis points, and equity volatility decreases by 45 basis points compared to the benchmark scenario. In the extreme case of specification [4] we assume a perfect correlation between temperature volatility shocks and long-run productivity shocks, which represents the case where agents perfectly respond to increasing temperature volatility by means of adaption efforts. This results in a sharp drop of the equity premium. Moreover, the counter-cyclicality between TVOL and TFP as well as the one between TVOL and output growth weaken significantly.

5.3 Welfare and Growth Effects of Temperature Volatility Risk

In the spirit of Bansal and Ochoa (2011b), we measure the economic costs of temperature volatility risk by means of welfare compensation of a change in the level of temperature volatility. The welfare compensation is expressed as a permanent change of agent’s lifetime utility relative to the economy with no temperature volatility risk. Formally,

where \(\varDelta \) represents welfare-costs, and \(\tilde{C}=\{\tilde{C}_t\}_{t=0}^{\infty }\) and \(\tilde{C}^*=\{\tilde{C}_t^*\}_{t=0}^{\infty }\) denote the optimal consumption paths with and without temperature volatility risk, respectively.

Table 7 reports welfare costs of temperature volatility effects in the benchmark economy and for the cases with positive correlation between TVOL shocks and long-run TFP shocks. In addition, costs are calculated for two values of the intertemporal elasticity of substitution to check if our results are qualitatively robust to whether the substitution effect or the income effect dominates. The first case is represented by \(\psi >1\), and more precisely, we use \(\psi =2\) as in the benchmark specification. To let the income effect dominate we set \(\psi =0.9\).

In our benchmark calibration, welfare costs amount to 9.1% of per capita composite consumption. This means that the bundle consisting of consumption and leisure of an agent living in an economy with temperature volatility risk needs to be increased by 9.1% in every state and at every point in time to give the agent the same utility as in an economy without temperature volatility risk. Since TVOL shocks have a large and persistent effect on productivity and other macroeconomic and financial variables, they produce sizable welfare costs.

In the case where long-run TFP shocks are positively correlated with TVOL shocks (\(\rho (\epsilon _x,\epsilon _{\theta })>0.5\)), welfare costs decrease substantially and become negative meaning that there are welfare gains from temperature volatility risk. In specification [2] with a correlation coefficient of 0.5 welfare costs are offset and turn into welfare benefits amounting to 41% of lifetime utility. We interpret the positive correlation between long-run TFP shocks and TVOL shocks as adaptation by agents to temperature uncertainty. Therefore, increases in temperature volatility that reduce TFP growth come with long-run macro shocks which in turn increase TFP growth. This hedge decreases overall risk and welfare costs. In specification [3] where we assume that long-run productivity shocks perfectly respond to TVOL shocks with a correlation coefficient of 1, welfare gains from temperature volatility risk are higher accordingly.Footnote 21

In case of a lower value \(\psi =0.9\) of the IES, results change quantitatively, but not qualitatively. With a lower IES the welfare loss in the benchmark case is about one third of the value for \(\psi =2\). Welfare costs are decreasing in the IES, since a lower IES implicitly makes the agent less patient, i.e., future consumption has a lower weight in the value function. This makes temperature volatility risk as a source of long-run macroeconomic risk less costly for the agent.

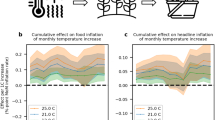

Expected Losses: To quantify the long-term effects of TVOL increases, we calculate expected changes in GDP and labor productivity growth for horizons from 1 to 50 years ahead after a temporary positive shock to UK temperature volatility. More specifically, we compare the cumulative growth in an economy in which TVOL negatively affects TFP growth to cumulative growth in an economy without TVOL effects. The shock sizes are one and two standard deviations of temperature volatility changes, i.e., 0.14 and 0.28.

Panels A and B of Table 8 report results for output growth and labor productivity growth. A single initial temperature volatility shock has a sizable long-run negative impact on both variables as it induces a long-lasting decline in productivity. Over a 50-year horizon, a one-standard deviation shock decreases both cumulative output and labor productivity growth by about 0.95pp. A two-standard deviation shock leads to a fall in cumulative output and labor productivity growth by about 1.9pp each after half a century. Hence, increases in temperature volatility affects economic activity negatively not only in the short but also in the long run by decreasing growth perspectives for output and labor productivity.

5.4 Temperature Volatility and Capital Depreciation

Global climate is projected to continue to change. The effects on the environment of the unstable climate are well known and—based on scientists views—are expected to become even stronger. In particular, temperatures will keep rising, the frost-free season (and growing season) will lengthen, hurricanes will become stronger, more intense and more frequent, and there will be further changes in precipitation patterns in the sense of more droughts and heat waves. More volatile climate conditions are therefore associated with stronger and more frequent extreme weather events. As a result, we should also expect stronger adverse effects of volatility in climate drivers on real economic activity (see Fig. 1). Benson and Clay (2004) argue that one of the channels through which natural disasters affect the macroeconomy is the destruction of the stock of capital. Based on these expectations and existing evidence, it is most likely that the increasing number of extreme weather events—induced by unusual weather dynamics—will exacerbate the process through which capital depreciates. In the spirit of Furlanetto and Seneca (2014), we account for a direct effect of temperature volatility (i.e., our climate change-related variable) on the capital stock by assuming a stochastic depreciation rate of capital. More importantly, we assume TVOL and depreciation rate shocks to be positively correlated. This is to stress the fact that innovations to temperature level variations exacerbate the overall effects of climate change and destroy capital more rapidly.

Formally, in the presence of a stochastic deprecation rate, the dynamic equation for capital reads:

where

Unexpected changes in the depreciation rate are represented by the shock term \(\epsilon _k\), and \(\rho _k\) measures the persistence of a depreciation shock. Time-varying capital depreciation helps to explain the high volatility of investment observed in the data. We calibrate the standard deviation of depreciation shocks to obtain an investment volatility of 6%, which is close to the data, and set \(\rho _k\) to 0.85. The main results produced by the new benchmark calibration featuring depreciation risk (BC) are reported in Table 9, specification [1]. Compared to an economy without depreciation risk (specification [2]), investment volatility significantly increases up to 6%, but this comes at the cost of an increasing volatility in labor and output. Due to higher risk, the equity premium increases by 127 basis points relative to the case with no depreciation shocks.

As pointed out in the beginning of this section, innovations to temperature level variations may exacerbate the overall effects of climate change and destroy capital via the increasing probability of natural disasters. To account for this effect, specifications [3] and [4] assume that TVOL shocks and depreciation shocks are positively correlated. Although this assumption reduces the counter-cyclicality of TVOL and the excess return, the equity risk premium increases. To understand this finding it is helpful to look at welfare costs of temperature volatility risk in the presence of stochastic depreciation of capital. The results of this analysis are displayed in Table 10. When TVOL shocks and depreciation shocks are uncorrelated (specification [1]), welfare costs of temperature volatility risk are not much affected compared to Table 7. Introducing a positive correlation between temperature volatility shocks and depreciation shocks (specifications [2] and [3]) increases welfare costs, and this effect is stronger the higher the correlation. This results from the fact that depreciation risk exacerbates TVOL risk. On the one hand, increasing temperature volatility has a negative effect on TFP growth, which reduces output and consumption. On the other hand, higher temperature volatility increases the depreciation rate, which decreases the capital stock. This has negative effects on production as well, which amplifies the response of consumption. Welfare costs of TVOL risk increase, as the overall volatility of consumption goes up substantially. The higher the positive correlation between temperature volatility risk and depreciation risk, the stronger is the amplification effect, which increases welfare costs further.

6 Evidence from an Endowment Economy

Using empirical evidence from a bi-variate VAR suggesting that a global temperature shock has a negative effect on consumption growth, Bansal and Ochoa (2011b) develop an endowment economy featuring long-run consumption and temperature risk to compute the welfare costs associated to rising temperatures. In a similar spirit to theirs, we first check whether there is a direct relationship between consumption growth and TVOL. The GC test suggests the presence of a negative and significant effect of TVOL on consumption growth for the period 1950–2015 (see Table 11).

A bi-variate VAR impulse response analysis shows that, 2 and 3 years after it occurs, a TVOL shock produces a drop in consumption growth of (approx) 0.4pp. This effect lasts for almost 5 years (see Fig. 11, Panel B). Based on this empirical evidence, we can account for the direct effect of TVOL shocks on consumption growth in the spirit of Bansal and Ochoa (2011b) and thus test whether TVOL risk still produces non-negligible welfare costs once we abstract from capital and labor decisions. We view this robustness check as a pure quantitative exercise to examine the sensitivity of our results to a different modeling choice. The model is briefly outlined here below.

Impulse response of consumption to temperature volatility. Notes: This figure depicts generalized impulse responses of consumption growth (\(\varDelta C\)) to a one-standard-deviation shock in temperature volatility (TVOL). Bi-variate VARs are estimated with two lags and include a constant. Solid “black” lines: IRFs. Dashed “dark grey” lines: 90% confidence bands. Dashed “light grey” lines: 68% confidence bands

The representative household is equipped with recursive preferences, as in Epstein and Zin (1989):

The intertemporal budget constraint is:

and the log SDF is:

where \(\theta = \frac{1-\gamma }{1-\frac{1}{\psi }}\).

Consumption growth and temperature dynamics are represented by the following system

where the shocks \(\epsilon _{c,t+1}\), \(\epsilon _{x,t}\), \(\epsilon _{\theta ,t+1}\) and \(\epsilon _{z,t+1}\) are independent of each other and are each distributed i.i.d. standard normally. The unconditional expected growth rate of consumption is \(\mu _c\). In this economy, short-run consumption shocks are induced by \(\epsilon _{c,t}\), whereas \(\epsilon _{x,t}\), \(\epsilon _{\theta ,t}\), and \(\epsilon _{z,t}\) indicate long-run shocks affecting the persistent stochastic components in consumption growth \(x_t\) and \(x^z_t\). The persistence of long-run consumption and temperature-related productivity shocks is measured by \(\rho _x\) and \(\rho ^z_x\), respectively. In this framework, the two distinct long-run components for consumption and temperature shocks feature the same timing of those innovations. As for long-run consumption shocks, temperature related shocks impact consumption growth with one lag, as suggested by the data.