Abstract

Over time, public universities have been involved in a process of modernisation based on a new concept of governance and managerial methods for increasing efficiency and effectiveness, as well as transparency and accountability. This paper aims to investigate the link between strategic planning systems and performance management systems in Italian universities by answering the following research question: to what extent do strategic planning tools contribute to performance management systems and, vice versa, to what extent can performance management systems help in the reshaping of universities’ strategies? To this end, we adopt a qualitative approach by conducting a multiple case-study analysis in the Italian context. Data are gathered through documentary analysis and interviews as primary research methods. Since scholars have mainly focused their attention on strategic planning or performance management in universities in isolation, the originality of this research lies in the attempt to connect these two important research fields, whose mutual interdependences are still to a certain extent unexplored. The implications of this study concern recommendations and suggestions for universities’ governance bodies to support their decision-making processes in the definition of their long-term objectives and performance management systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Over the last 20 years, in Italy, as in the rest of Europe, a series of systemic changes has occurred in the university sector. These have strongly promoted the adoption of new governance models and consequent strategic choices. The determinants include: the instances of change triggered by reforms in the governance of the main public sector organisations; and the need to make higher education organisations more effective and efficient. This has required systemic structural interventions both in organisational models and internal decision-making mechanisms.

The wider process of modernisation has been inspired by the reforms following the pervasive wave of New Public Management (NPM) (Hood, 1991; Lapsley, 2009; Pollitt, 2007) and in subsequent movements such as New Public Governance (Osborne, 2006). From this perspective, there has been increasing focus on the need to strengthen the governance of public organisations by providing them with strategic tools able to support decision-making processes and, at the same time, the need to appropriately monitor the efficiency and effectiveness of the services offered, ensuring transparency in administrative actions and accountability (Broadbent & Laughlin, 2009; Jansen, 2008).

The reforms of university governance in Italy culminating in Law 240/2010 (the so-called “Gelmini reform”), which is characterised by a centralised and top-down structure and by considerable uncertainties regarding certain central nodes of the new governance envisaged for universities, are set in this context. In this sense, the analyses carried out attempt to distinguish between the systemic governance orientation, which concerns the contextualisation of universities in their affiliation to the public sector, and specific university governance, which is more focused on examining the tools available for internal decision-making and organisational mechanisms.

The reform of universities has increasingly encouraged the definition, from a multi-year perspective, of development guidelines, pushing for the implementation of a planning process and, at the same time, introducing a performance management cycle, similar to other public administrations. In fact, the regulations for university planning have concerned the adoption of a Three-Year Planning Document (TYPD), which can be revised annually, consistent with the ministerial guidelines that divide the specific objectives to be reached and the possible lines of action, alongside the related operational indicators. As documents with a strong strategic value, they assume therefore a central role in achieving the main objectives related to a university’s mission.

Seizing the opportunity related to regulatory changes, the most proactive universities have attempted to develop a real Strategic University Plan (SUP) with the same time horizon. This choice is part of a managerial dynamism that several universities have chosen to adopt by reconfiguring the tools and boundaries of strategic governance. In this way, they have been able to demonstrate the degree of the spread of “managerialism” within their complex organisational structures, which are required to support innovation but are often subject to constraints and rules that limit their action.

Simultaneously, the performance management cycle is being affected by another important three-year planning document, the Performance Plan (PP), which is a tool that should define the objectives, indicators, and targets of universities’ activities. The PP establishes the main elements for the annual measurement, assessment, and reporting of performance, which, at the end of the year, should be expressed in the Performance Report (PR).

In this context, this paper investigates the link between the two dimensions (strategic planning and performance management) within universities by answering the following research question: to what extent do strategic planning tools contribute to performance management systems and, vice versa, to what extent can performance management systems help in the reshaping of universities’ strategies?

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Sections 2 and 3 provide a review of the relevant literature regarding the topics of strategic planning and performance management, respectively, both starting from public sector organisations in general and then focusing on universities in particular. Section 4 details the research methodology adopted. Section 5 presents the results of the analysis conducted for the three case studies. Finally, Section 6 discusses the results and presents the conclusions.

2 Strategic planning in public sector organisations and universities

The use of a strategy in public sector organisations, while the focus of significant debate in the literature, has met with broad consensus regarding its implications for performance. In particular, this has happened at a time when the functioning of public organisations has attracted the attention of results-oriented management. Recent studies in this field confirm that “managerial autonomy” and “result control” have independent and positive effects on an innovation-oriented culture in public sector organisations (Wynen et al., 2014).

In order to establish trajectories and make objectives measurable, strategic guidance and co-ordination instruments are needed. According to Boyne and Walker (2010, p. 186), “strategy is believed to set a direction for collective effort, help focus that effort toward desired goals, and promote consistency in managerial actions over time and across parts of the organisation”. Indeed, the focus has been on using strategic planning as a precursor to the implementation of a more pervasive, process-oriented approach, such as strategic management. Although strategic management is often discussed as an extension of strategic planning, and the two terms often are confused and used interchangeably, they are by no means synonymous (Poister & Streib, 1999).

Strategic planning has been defined as a disciplined effort to produce fundamental decisions and actions that shape and guide an organisation (Bryson, 1988). It blends futuristic thinking, objective analysis, and the subjective evaluation of goals and priorities to chart future courses of action that will ensure the long-run vitality and effectiveness of the organisation. According to Bryson and Edwards (2017, p. 320), “strategic planning consists of a set or family of concepts, procedures, tools, and practices meant to help decision makers and other stakeholders address what is truly important for their organisations and/or places”. The underlying assumption that drives public organisations to use strategic planning is often considered to be that it guarantees a result-oriented approach and better performance.

However, the relationship between strategic planning and strategic management needs to be further investigated and understood. In its broader vision, the system considers strategic planning as the first step in a model oriented towards the measurement and evaluation of results. In particular, in public sector organisations, the use of strategic plans is a way of reducing the political-institutional meaning of choices through strategic guidelines and objectives. In this sense, the strategic plan enables the application of performance management.

Strategic planning is normally considered the main element, but not the essence, of strategic management, which instead uses several phases considered outside of the realm of planning (in the strictest sense of the term) that are related instead to resource management, the implementation of activities and processes, and control and evaluation (Bryson, 2011; Poister & Streib, 1999). Strategic planning should be understood as a set of concepts, processes, and tools to determine “what an organisation is”, “what an organisation does”, and “why it does it” (Bryson, 2004).

From this perspective, strategic planning has been widely used in strategic management applied to the public sector (Barzelay & Jacobsen, 2009; Bryson, 2011; Poister & Streib, 2005). In addition, strategic management tools, such as the balanced scorecard (Kaplan & Norton, 1996) and strategic mapping (Kaplan & Norton, 2000), have proven to be particularly useful in the public sector because they are able to make the public value more perceptible for the various stakeholders (Talbot, 2011).

Since its conceptualisation in the 1960s (Bolland, 2020), strategic management has become a diversified field that ranges from the analysis of strategy in businesses to that of strategies in non-profit organisations and the public sector. Its adoption was partly a response to environmental turbulence in the 1970s, which made the traditional planning approach antiquated, and partly a reaction to the non-functioning of some management models, such as the Planning, Programming, and Budgeting System (PPBS), with strong demands in terms of information processing and management capacity (Johnsen, 2015). Since the 1980s, therefore, public sector organisations have also begun to make more consistent use of strategic management concepts and techniques and it is now common in the public sector in many countries and at different levels of government (Boyne & Walker, 2004; Bryson et al., 2007; Poister & Streib, 1999).

According to Poister and Streib (1999, p. 308), “effective public administration in the age of results-oriented management requires public agencies to develop a capacity for strategic management, the central management process that integrates all major activities and functions and directs them toward advancing an organisation’s strategic agenda”.

While it is assumed that organisations in general will attract the attention of different stakeholders, it is important to consider how public sector organisations are by their very nature more prone to political processes than other organisations, thus needing to use tools such as stakeholder analysis to analyse actors, interests, and power relations, as well as to find ways other than business to motivate employees (Wright & Pandey, 2011) and associates. This is appropriate when the use of documents with a strong strategic purpose becomes part of the set of tools available to public organisations, comprising elements, structures, and methods borrowed from those used in for-profit organisations.

As far as universities are concerned, starting from the 1990s, studies such as that of Conway et al. (1994) have emphasised the importance of the role of users in defining strategic plans and, in particular, of students in outlining the mission of tertiary education organisations, as well as from a competitive point of view in relation to the surrounding environment; more generally, some contributions have highlighted how to shape a process of mid- to long-term planning in universities (and why this is necessary) (Holdaway & Meekison, 1990; Lerner, 1999; Rowley, 1997). More recently, some studies on the theme have focused on specific territorial contexts, confirming the close link between strategy and the reference environment (Howes, 2018; Kenno et al., 2020; Luhanga et al., 2018; Moreno-Carmona et al., 2020; Mueller, 2015). With reference to the relationship between the strategic dimension and performance, strategic management is certainly at a higher level and can be interpreted as a performance management process at the strategic level (Poister, 2010). The role of strategic management focuses on the actions to be taken to position the organisation so that it can move into the future, while performance management is largely concerned with the management of current programs and current operations. Performance management in public organisations, specifically in universities, will be discussed in the following section.

Traditionally, because of the specific nature of their activities, universities have been considered different institutions from businesses and other public sector organisations. For this reason, studies on universities have, for a long time, not focused on how they operate, how they are managed, or how they conduct their decision-making processes. In these organisations, inputs, outputs, and outcomes are often not clearly established and consequently the measurement system appears severely limited. In the late 1990s, a pioneering study aimed at detecting the presence of strategic planning in European universities found that just over half of the universities surveyed had strategic plans in the form of written documents designed to prioritise objectives; in most cases, however, the strategic plans had an incentivising rather than a prescriptive function (Thys-Clément & Wilkin, 1998).

Although the literature on university strategies is not still well developed, some studies have shown that the mere focus on strategic planning in practice may not be particularly relevant. Such practice would be resolved in verifying that the goals achieved fit the objectives. It would, therefore, have a formal or neutral role. Other studies have proposed strategic planning as an indispensable tool for improving performance in these organisations, with particular reference to colleges and universities (Cowburn, 2005; Dooris et al., 2004; Fathi & Wilson, 2009; Ofori & Atiogbe, 2012).

In addition, applied proposals to implement performance measurement systems appear to be applicable and capable of measuring the achievement of results in these organisations (Johnes, 1996; Johnes & Taylor, 1990). The higher education literature identifies several limitations in higher education performance: the lack of data availability; the presence of too many indicators that are not particularly useful in representing performance; and confusion between input, processes, and outcomes (Layzell, 1999).

Because of their specific nature, universities would require as a priority “models and systems of strategic awareness, management and progress that recognize the issues, contexts and processes that actually shape their strategic change” (Buckland, 2009, p. 533).

3 Strategic implications for performance management in public sector organisations and universities

Strategic planning and performance management are closely interconnected. In fact, if on the one hand it is difficult to achieve good results without an adequate strategic planning process, on the other hand it would make no sense to define mid- or long-term objectives, and the corresponding operational actions, without then verifying if, how, and to what extent they have actually been met and what results they have produced (Bryson, 2003, 2004).

Despite this indisputable link, research in public management has mainly focused on performance rather than on strategy (Cepiku, 2018). This is probably due in part to the reforms that, over the last 30 years, have introduced this concept (of Anglo-Saxon origin) into the public sector by increasingly formalising its reporting (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008).

Performance measurement (and management) systems are normally aimed at identifying performance targets, enabling the assessment of individuals, and informing managers when to take action to prevent deterioration in performance or when it becomes apparent that targets have not been met (Neely et al., 1994). The result is the need for organisations to allow the performance measurement system to support the achievement of objectives and the efficiency and effectiveness of the strategic process.

Several contributions have focused on performance management in the public sector in general (Arnaboldi et al., 2015; Broadbent & Laughlin, 2009; Cepiku et al., 2017; Dal Mas et al., 2019; de Bruijn, 2002; Jansen, 2008; Kearney & Berman, 2018; Lee Rhodes et al., 2012; Van Dooren et al., 2010; Van Dooren & Van de Walle, 2016). Others, however, have dealt with the topic of performance in specific public organisations. To name just a few, Smith (2005) analysed the topic in the healthcare sector, Mussari et al. (2005) discussed the performance of local public companies, Grossi and Mussari (2008) attempted to identify the possible different dimensions of local governments’ performance, Cohen et al. (2019) focused on the relations between local government administrative systems and their accounting and performance management information, highlighting the existence of a mismatch between the two, Bracci et al. (2017) examined the implementation of a performance measurement system in two public entities, Papi et al. (2018) elaborated and tested a model for measuring public value in a municipality, and Xavier and Bianchi (2020) investigated how performance management systems can support governments in crime control.

These studies have sometimes highlighted the important difference between performance measurement and performance management systems (Arnaboldi et al., 2015; Broadbent & Laughlin, 2009). In fact, the effort to translate results into numbers should not be a mere bureaucratic exercise but should result in the opportunity to use these data to improve the provision of services to the public (Jansen, 2008; Van Dooren & Van de Walle, 2016).

On this point, Bouckaert and Halligan (2006) specified that a complete performance management system should follow a logical sequence with three main steps: (i) measuring; (ii) integrating; and (iii) using. Merely measuring, which means collecting and processing performance data into information, is insufficient if such information is not incorporated within a broader system of documents, procedures, and discourses and subsequently used to improve decision-making, strategies, results, and accountability.

Incorporation, which is what this paper investigates, deals with including performance information in the policy, financial, and contract cycles (Van Dooren et al., 2010). Specifically, the policy cycle starts from the strategic plan (which defines major objectives and targets for resources, activities, outputs, and outcome), continues with the implementation, then the monitoring, followed by the evaluation (the reports from which incorporate performance information), and this feeds into the next strategic plan. The financial cycle includes budgeting and is ideally embedded in the policy cycle.

Regarding performance in higher education, this theme has attracted the attention of many scholars who have investigated the peculiarities of performance measurement tools in universities (Balabonienė & Veþerskienė, 2014) or how they are applied in some territorial contexts. For example, Higgins (1989) explored the case of British universities, Modell (2003) dealt with the subject in Swedish tertiary education, Guthrie and Neumann (2007) outlined the establishment and mechanisms of a performance-driven Australian university system, Ter Bogt and Scapens (2012) focused on the case of the universities of Groningen in the Netherlands and Manchester in the UK, Kallio et al. (2017) emphasised the problems of measuring quality aspects in academic work in the Finnish case, and Dobija et al. (2019) provided experiences from Polish universities. These contributions highlight that different types of performance management are used in universities and that its scope varies among different actors, depending on diverse external and internal factors. Moreover, measuring performance is difficult in knowledge-intensive organisations, where quantitative indicators may fail in catch the complexity of such institutions. Often, performance management is adopted by a university simply to comply with regulations or gain external legitimation, rather than to make a real change in the use of resources to the enhance efficiency and effectiveness of their activities.

Aversano et al. (2017) examined the evolution of performance management systems in the university context. Their study confirmed that, beyond the desired intentions, the focus is still strongly on the production of the data rather than its use to provide a holistic view of university performance that can guide strategies, programs, and activities.

Moreover, as pointed out by several authors (Bower & Gilbert, 2005; de Bruijn, 2002; Francesconi & Guarini, 2018; Goh et al., 2015; Van Thiel & Leeuw, 2002), one of the distinctive characteristics of strategic planning and performance management in public organisations, including universities, is connected to the issues encompassing resource allocation and budgeting practices. In fact, assigning adequate resources through the budgeting process is crucial in order to translate strategic objectives into operational objectives. Further, a feedback loop exists as, especially in recent years, the results achieved (as measured via performance management) are increasingly used by the governance body in decision-making related to budgeting.

Recently, Deidda Gagliardo and Paoloni (2020) took a snapshot of the state of the art of performance management in national universities, highlighting its strengths and weaknesses as well as predicting future challenges.

Examining the Italian context, the Italian experience has been marked by a reform in 2009 (Decree no. 150/2009), which highlighted the inadequacy of existing planning and control systems, as well as the absence or insufficiency of mechanisms for measuring and managing performance in public sector organisations. Nevertheless, to date, there remains no empirical evidence of the concrete usefulness of the tools introduced and their effective capacity to produce improvements in terms of effectiveness and efficiency in public administrations (Arnaboldi et al., 2015).

As illustrated, academic literature on the two research topics (strategic planning and performance management in universities) taken in isolation is quite extensive. However, the review of the literature highlights how few contributions directly link the two streams of research, looking for their interconnections (Biondi & Cosenz, 2017; Campedelli & Cantele, 2010; Cosenz, 2011; Francesconi and Guarini, 2018). In particular, the study conducted by Bronzetti et al. (2011), examining the planning methods of Italian public universities and analysing the related strategic plans under the dual dimension of process and content, identified as a future study trajectory the need to investigate the use of this document for decision-making purposes also in relation to the PP. The current paper attempts to join the debate by answering this call.

4 Methodology

In order to address our research question, this paper adopts the case study as a qualitative approach. Case study research is described as a method with which: “[…] the investigator explores a real-life, contemporary bounded system (a case) or multiple bound systems (cases) over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information, and reports a case description and case themes. The unit of analysis in the case study might be multiple cases (a multisite study) or a single case (a within-site case study).” (Creswell, 2013, p. 97).

Our analysis is carried out through a comparative study of the strategic planning tools and their degree of influence on the performance management systems of three Italian state universities, identified as case studies.

We applied a multiple case studies methodology with an exploratory purpose to understand “how” and “why” certain phenomena occur in a specific economic-social context (Stake, 2005; Yin, 2003).

Our decision was also motivated by interest in analysing both the single universities in detail and comparatively, in order to investigate similarities, differences, and patterns across the cases (Gustafsson, 2017). In this sense, the analysis is also comparative (Yin, 1993).

The choice of cases was driven by selecting universities that have been early adopters of these planning tools, thus being pioneers in the Italian context. This made it possible to carry out a longitudinal study for at least two complete planning cycles, highlighting their development characteristics from a temporally consistent perspective (Pauwels & Matthyssens, 2004). Although each university examined belongs to a different complexity group according to a recent classification (Rostan, 2015), the choice of strategic planning was unrelated to this dimension.

The study was based on the same level of observation, focusing on how the three universities proceeded with the introduction of the strategic planning system over time and which framework they have been using to link it to the performance management system. For all three universities, the analysis took as reference at least two programming cycles, albeit with a different time horizon.

The analysis is supported by the different context and dimensional variables of the three universities (see Table 1). These universities are differentiated by year of foundation (one founded in the second half of the nineteenth century, the other two more than a century after), by being located in different geographical areas (North, Central, and South Italy) and therefore having different direct competitors, as well as by size, in terms of student population, departmental articulation, active study courses, tenured teaching staff, and technical-administrative staff.

The research design is structured into different phases. Initially, we created an interpretative framework that could homogeneously highlight the areas under investigation. Hence, the variables that could better highlight the elements characterising the three universities were identified. Subsequently, the three case studies were reconstructed and illustrated. To this end, data were collected through a triangulation of sources. First, we carried out a documentary review of secondary sources, namely institutional documents (Corbetta, 2003) pertaining to strategic planning and the performance management cycle of the three universities. Specifically, we reviewed:

-

three-year planning documents;

-

strategic plans;

-

three-year and annual budgets;

-

reports on periodic monitoring;

-

performance plan and/or integrated plans;

-

performance reports;

-

minutes of the meetings of the academic bodies; and

-

quality manuals.

These documents are publicly available from the institutional websites of the universities.

Subsequently, evidence was complemented using primary sources, namely semi-structured interviews (Longhurst, 2003; Qu & Dumay, 2011). The interviews were with academic administrative managers involved in the strategic planning and performance management processes, and who actively participated in the drafting of these documents in each of the universities investigated. The interview protocol was based on open questions agreed by the authors, aimed at investigating “how” and “why” these processes have been developed over time. The answers helped the authors to understand the content of the documents and the dynamics underlying their elaboration.

5 Results

Evidence gathered from the three case studies is presented according to the following structure, aimed at facilitating the comparison and highlighting the peculiarities among them:

-

1.

the development of strategic planning process;

-

2.

articulation and content; and

-

3.

linking strategic planning with the performance management cycle.

5.1 The development of the strategic planning in the three cases

The three case studies may be considered as early adopters of a structured strategic planning process, in line with the relevant regulation (Law no. 240/2010). However, they have different starting dates. The first SUP of University A was issued in 2012 (although the process began in 2010), while University B’s first SUP was issued in 2013. University C can be considered not just a pioneer but a precursor of what the regulation would require, in that it started the formalisation of its planning process even before the reform came into force, in 2009.

University A’s SUP was entitled “Towards 2018” to symbolise the far-sightedness of a vision aiming for strong innovation. In the preface, according to the Rector’s assertion, the document represents a challenge to enable the university to “compete and collaborate, with the most prestigious universities to fulfil all three of its institutional missions: research, teaching, and innovation” (SUP 2012–2014, p. 1).

Since its inception, the SUP has been considered a document to support the Rector in his mandate by involving the top management of the organisational structures considered crucial for the university regarding its preparation (from the central structure to the individual departments, schools, and research centres). A special team was created to work on this, comprising an internal expert in corporate strategy and various collaborators. This team was also supported by the “Planning and Evaluation” Office, an organisational unit of the “Strategic Planning and Programming” area. The SUP of University A is, therefore, the result of meetings, discussions, and comparisons with the main competitors, which creates a shared strategic view of the governance of that university. Creating such “shared strategic ambition” is fundamental to mapping the strategic paths to be adopted and makes it possible to consider the plan as an actual guiding document for the university, shared by all the organisational units.

Hence, the strategic planning process of University A passes through several stages. As mentioned above, the first stage involves mapping the strategic ambition of the main subjects in charge of the university’s governance (phase 1) to verify their degree of alignment (phase 2). These two “interlocutory” phases are followed by an “objective” analysis of the internal and external environment (phase 3) to verify, in the case of conflicting subjective perceptions regarding a topic or objective, which is the correct one, but also in case of agreement, to test the validity of the concordant “subjective” perceptions. In the opinion of those who have experienced it first-hand, this is a critical “dialogical” stage in which different actors participate and discuss to reach a joint agreement. This makes it possible to reach a greater degree of alignment (phase 4) on which University A’s strategic goals should be based, which are then submitted for the attention of stakeholders before creating the final draft of the plan (phase 5). Moreover, University A has also used external consultants for specific aspects of the plan for which there was no in-house expertise.

Regarding University B’s strategic planning process, this happens in a somewhat different way. In fact, the starting point of the process is not the SUP but the TYPD. The TYPD is issued by the Rector considering the programmatic indications coming from the relevant Ministries, the proposals of the Academic Senate (SA), and the indications of the Evaluation Board. The TYPD is part of a multi-year planning process that aims to achieve the university’s effective strategic governance and management. The TYPD is an act of political direction since, drawing inspiration from the university mission, it illustrates the reference values of the government action and, from them, at the strategic level, the general objectives to be pursued regarding the typical institutional functions (research, teaching, third mission), as well as the transversal and support functions (personnel, construction, communication). The planning process then continues with the drafting of a SUP. This document defines in a more concrete and detailed way what is reported in the TYPD. In the preparation of such a document, the Rector is assisted by the Vice-Rectors (covering the areas of: teaching; research; university networks; schools, societies and institutions; relations with the labour market; innovation and technology transfer; infrastructural and workplace safety policies; and relations with university governing bodies and regulatory matters). From the analysis of the last TYPD and SUP, a link emerges between these two strategic planning documents and the document that formalises the performance cycle [called the Integrated Plan (IP), which will be discussed later]. In fact, it has been established that the SUP will undergo a periodic review, and that the TYPD itself may undergo revisions, on an annual basis, concerning the preparation of the IP.

However, the planning process seems less structured and participatory than in University A. As required by the regulations, and as confirmed in the words of one of the managers interviewed: “The political office is responsible for political guidance, while the administration is responsible for administrative management and assists the political office. On the one hand, the SUP and TYPD are both policy documents and are, therefore, within the sphere of competence of the governing bodies. They are drawn up by the Rector and Vice-Rectors, and then approved by the Board of Directors. On the other hand, the Integrated Plan is an administrative document.”

Nevertheless, it is likely that the Vice-Rectors informally consult the General Director (GD) also regarding the definition of strategic programming documents.

Another difference from University A is that, in University B, the entire process is carried out internally, without involving external consultants. Moreover, we did not find any evidence regarding periodic monitoring of the SUP at University A. In contrast, University B draws up an intermediate monitoring document to check to what extent the objectives have been achieved and, if necessary, to modify decisions and actions. This check takes place one and a half years after the approval of the SUP. A final report is then issued at the end of the three years. While the strategic planning process is top-down (since once the SUP is approved, the departments have to draw up their own strategic plans), drafting the report on the implementation of the SUP is a bottom-up process. Each structure, starting from its strategic plan, verifies in itinere the achievement of the objectives for teaching, research, and the third mission, respectively. These reports are then consolidated and summarised at the central level by the relevant Vice-Rectors.

Moving on to the strategic planning process of University C, as highlighted, this is the university that started the formalisation of its planning process earliest, in 2009. The first SUP had a time horizon of five years and included the triennial strategic guidelines (2010–2012). This is a peculiarity in comparison with the other cases, in that the TYPD is not a separate document but embedded in the strategic plan itself.

As declared in the document, the process to issue the SUP involves much participation and different actors are engaged (like University A). In fact, the aim is to gain consensus among all the university’s stakeholders (students, academics, administrative staff), support the governance, and facilitate decision-making processes and activities, based on participation and shared ideas (SUP 2010–2014, p. 4). This first document was drawn up by a Commission made up of delegates and experts, with an advisory and consultative function of the Rector, with a specific mandate to support the preliminary stage of the university’s strategic planning documents. The document was then presented to the university’s governing bodies, ultimately incorporating the requests that emerged from its public presentations. As stated by an interviewee: “The whole academic organisation is involved in providing the data; departments have also to adapt their strategic plan to the university’s plan”.

This path of elaboration, redefinition, and involvement, although taking more time than expected, enhances legitimation, and strengthens consensus regarding its strategic vision by defining quite detailed and shared lines of action. For University C also, the entire process was carried out without involving external consultants.

The drawing up of this document started from the analysis of the university’s current situation, measured through the principal indicators adopted for the assessment of the university system. At the same time, the SUP considered the need for financial sustainability and enhanced efficiency and effectiveness of the university’s activity. Coherently, the delegate of the Rector for strategic planning pointed out that the main objective of University C for the next five years was enhancing the quality of performance by reducing costs and increasing revenues.

In the preface of the document, written by the Rector, we learn that the SUP will also assist in providing the main variables to be used in the next triennial strategic guidelines. In fact, the Ministry assesses and finances higher education entities based on their performance indicators and their improvement according to the objectives. This is an interesting point, which highlights a strong link between the SUP and the triennial strategic guidelines: the strategic plan initially includes the previous triennial strategic guidelines, and at the same time, conversely, is the basis for extracting information to create subsequent guidelines. Moreover, as we will see better later, the SUP also refers to the IP.

Unlike University B, the achievement of objectives is not periodically evaluated, or at least it is not formalised in any way.

5.2 Articulation and content of the documents in the three cases

The three case studies show the SUPs’ different approaches and content. These differences depend on the meaning that each university has given to the SUP, what the motivation is, and what the relationship is with the TYPD. The relationship with the latter is, in fact, a conditioning factor for the entire content of the SUP.

In University A, as already mentioned, the process of formulating the SUP began with several meetings and discussions to map and compare the subjective perceptions of the main subjects in charge of strategic governance (Rector, Vice-Rectors, Faculty Chairs, chairman of the Board of Departmental Directors, GD). To formulate a document involving the strategic nodes of the university’s future, several critical variables were considered regarding the definition of a common strategic ambition: internal structure; external structure and specific context (sector, competitors, potential entrants, complementary companies, customers, suppliers, financing bodies, communities, etc.); mission and vision; internal and external objectives; and strategies and three-year actions. As highlighted in the methodological attachment to the SUP 2012–2014 (p. 3), this document, which precedes all forms of planning and programming for the whole organisation, has been designed in such a way that it can be linked to the strategic guidelines identified, the TYPD, and the PP.

People involved were asked to describe in narrative terms their perception of University A’s strategic ambition, based on which a strategic map was created, leading ultimately to the issuing of the final SUP. The final version was based on the identification of ten objectives to be achieved through specific strategies: strategic reorganisation of research and educational activities; improving University A’s local, national, and international visibility; integration with other close universities and higher education institutions; integration with the territory; improving University A’s student services and attractiveness; enhancing the teaching staff’s potential; enhancing the technical and administrative staff’s potential; reorganising the internal structure; providing new and better spaces; and assuming a transversal sustainability orientation.

As well as focusing on the three macro areas (teaching, research, and third mission), this document also examines each objective in relation to strategies achievable through specific actions (measured via indicators).

The second strategic planning experience was developed under different conditions and initially appeared to have fewer expectations. Moreover, governance conditions had changed [turnover of the Rector and Board of Directors (BoD)] and the change in the SUP’s style appeared to be an element in distancing itself from the previous approach, while maintaining a common basis.

This emerges clearly from examining the document and the responses gathered from those who collaborated in drafting both SUPs.

The second SUP was also developed through a co-owned process that involved the entire academic community and took place in two phases. This is a completely different document, less voluminous in its content and without any methodological details, although the approach has changed.

The first phase was dedicated to identifying the university’s objectives by sharing strategic guidelines and defining the actions to be pursued in 2016–2020. The Vice-Rectors were primarily involved and, in collaboration with the reference structures, helped identify the primary objectives and strategies by dedicating ample space for all the university’s components to collaborate. The second phase was aimed at systematising the collected material, clearly defining the vision, mission, objectives, strategies, actions, and monitoring indicators, and subsequently preparing the final document.

In this sense, the interviews show that the strategic planning in these different periods was emblematically the reflection of the two different styles of governance. In the first SUP, the university wanted to demonstrate strong choices and changes, justified by work carried out with a scientific method but that also ended up creating important breaking points within the organisation. The second SUP focused more on the concept of inclusion, utilised a different leadership approach, focused on objectives other than transversal, and focused on the central administrative apparatus’s functioning. The structure of the document was based on the identification of five macro-objectives: promoting impactful research; creating a transformative study experience; acquiring an international dimension; acting as a catalyst for innovation; and guaranteeing a sustainable academic future. Subsequently, each macro-objective was broken down into objectives for which strategies and actions were identified, confirming the structure followed in the first SUP.

In University B, the SUP is divided into three separate sub-documents in more detail: a Strategic Research Plan (SUP-R); a Strategic Teaching Plan (SUP-D); and a SUP for the Third Mission (SUP-TM). These plans were prepared by the Vice-Rectors; in particular, as far as the third mission is concerned, University B has decided to establish three Vice-Rectorates who together promote and monitor: innovation and technology transfer activities; relations with schools, companies, and institutions (so-called public engagement); and relations with the world of work. As stated by an interviewee: “The idea behind the choice of the strategic plan, articulated by areas, is to favour comprehensiveness, taking care of each area of detail. The strategic plan must be firmly linked to the lines of academic innovation; it also requires to be based on a broad consensus implemented through an increasingly participatory and inclusive procedure, involving the collegiate governing bodies, departments and schools.”

Unlike the other two cases, which are more deeply rooted in time, the first SUP relates to the period 2015–2017, while the following SUP refers to the 2018–2020 three-year period. Analysing the two documents from a longitudinal perspective, they are identical regarding the division into the three macro-areas with which the university is concerned (this division was agreed at a central level in adherence with the three institutional activities). However, there are small changes in structure and content, partly due to natural refinements in preparing the document, and partly resulting from a change in governance (Rector and Vice-Rectors). As far as the SUP-R is concerned, its structure mirrors the two programming cycles, defining the general strategic objectives starting from the TYPD, which in turn are then translated into specific strategic objectives for which indicators are identified and actions to support them are suggested. The SUP-D, in its first formulation, after explaining the mission and vision for teaching, indicated objectives, actions, and monitoring/success factors. The second version, however, begins with the formulation of the overall strategy for the university’s didactics, moving to an “as is” analysis based on data derived from the university’s Indicators Sheet (made available by ANVUR, the Italian National Agency for the Evaluation of the University and Research Systems) to identify strengths and weaknesses, subsequently identifying four general “strategic objectives” (called “general lines”), each with (specific) “objectives” and “actions”. The SUP-TM has undergone major changes in the transition from one three-year period to another. In its first formulation, the SUP-TM 2018–2020 was a descriptive report of the initiatives conducted by the university (e.g. activities related to lifelong learning, the Palladium theatre, the Job SOUL platform, summer schools, and social reporting); the SUP-TM 2018–2020 is much more structured, articulating the three established Vice-Rectorates’ third mission areas and indicating for each of them the general strategic objectives (called “lines of intervention”), outlined in actions and a proposal of indicators for evaluating their achievement.

There is no direct evidence of how the Vice-Rectorates proceeded operationally in elaborating the individual plans, although in his policy document the Rector encouraged a “participative” process and, from the minutes of approval of the last SUP by the SA and the BoD, it can be seen that: “the document is the result of collective work, which has been widely participated and shared”.

It is only in the SUP-TM 2018–2020 that it is clearly stated that, in order to draw up the document, “it was considered appropriate to schedule meetings with the individual Departments with the intention of carrying out a complete survey of the experiences and good practices in progress, as well as to submit the main strategic lines represented here, in order to gather possible stimuli and suggestions for improvement from the departmental realities that have so far largely contributed to the development of the Third Mission” (SUP-TM 2018–2020, p. 40). The data appear to be important as they show how the content of the document is the expression of sharing and participation with the individual departments representing the main driving force of the university, despite their autonomy.

The administrative bodies also participated, as it emerged that the Vice-Rectors, despite having prepared their respective plans without consulting the offices, informally consulted the GD and various structures. This is evident both from the interviews and the minutes mentioned above, where it is stated that the Rector, in addition to thanking the Directors, also thanked the GD as well as the BoD “for having contributed effectively, each for the aspects within his or her competence, to the drafting of the Plan”.

In University C, regarding the first document issued in in 2009, by integrating the strategies outlined in the triennial strategic guidelines, the Rector declared: “The document outlines the roadmap of the university’s actions in the main areas, namely education, student services, research and knowledge transfer, internationalisation, human resources, organisational structure and building plan”.

The initial aim was to address areas considered of absolute strategic importance, i.e. the three macro-areas (teaching, research, and the third mission), focusing on describing the university, context analysis, and identifying objectives and related targets and indicators. This immediately clarified the meaning to be given to the instrument. Transversal to the whole document, in contrast to the other two cases considered, is the financial dimension and the link between objectives and the forecast of financial flows in and out. As claimed by an interviewee: “The key point for the university is the improvement of all the university’s performances in relation to parameters of the ordinary financing fund, parameters of the three-year plan, but also to all those parameters that can bring the university back to a better position in national and international rankings”.

The SUP is articulated in different sections. It begins by describing the university (number of students, professors and lecturers, administrative staff, etc.) and then illustrates its situation “as is” through a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis. The SWOT analysis represents the starting point for the elaboration of the SUP. The SWOT analysis, used as a method to define strategy, focuses primarily on the following points: training, student services, and internationalisation; research and knowledge transfer; and human resources.

Consequently, the document then highlights seven “strategic lines” of interventions: teaching; students services; research and knowledge transfer; internationalisation; human resources; organisational structure; and building plans. For each strategic line, different indicators are derived from the current legislative regulations. Finally, a summary table synthesises objectives, actors, starting year, and human and financial resources allocated for each strategic line.

In the conclusions, the Commission states that the plan is intentionally concise, and it is not further expanded on or detailed in order to allow the governing bodies to define methodologies and responsibilities for implementation. It is also stated that an essential condition for initiating, sustaining, and continuing the process is a control both for the implementation and monitoring of the plan.

The second SUP shortens its time horizon to three years (2014–2016). The document appears less readable, has no summary, is full of tables, and has few descriptions. It includes again a SWOT analysis and subsequently describes the strategic lines, which are almost the same as in the previous SUP. However, unlike the previous SUP, it does not contain a summary table with the objectives, actors, timing, and resources for each strategic line. Moreover, no final considerations or conclusions are displayed; there is only an initial page, written by the delegate for strategic planning, quickly commenting on “how” what they planned in the SUP 2009–2013 had been achieved, and stating that the university had to manage the shortfall, which was worse than expected. Overall, it considers that the general objective of “enhancing the quality of performance by reducing costs and increasing revenues” was achieved.

This document appears to be less focused than the first plan and was probably less participatory.

The SUP 2016–2018 starts with the macro-objectives for the following three years: enhancing the quality of teaching, research, and internationalisation; increasing commitment toward the third mission; and pursuing and implementing the university’s quality assurance system. Again, it opens with an analysis of the context, subsequently identifying the strategic lines: didactics; student services; research; internationalisation; third mission; and staff required. For each there are now clearly highlighted objectives, related actions, and coherent indicators. The document also appears to be more understandable thanks to summary tables for each strategic line.

The current SUP (2019–2021) is the shortest in length (35 pages). It appears as an extract from the minutes of the BoD. Both the format and the content are similar to the previous SUP. The only significant difference relates to the strategic lines, with the inclusion in the summary tables of a column highlighting the target.

From the documentary analysis of University C and the interviews, it emerges that there is no real TYPD among the planning documents. The triennial strategic guidelines are somehow included in the SUP. This entails that it is not easy to understand the relation between the two, i.e. whether the strategic planning documents’ strategic objectives are derived from the triennial strategic guidelines or vice-versa.

In all three cases, the SUPs were created in response to the needs arising from governance reforms and different decision-making and management tools at their disposal. In University A, the SUP’s adoption is more than a methodological and recognition exercise, as evidenced by the document that preceded the first concrete plan. The document also makes explicit the decision to promote integration between the TYPD and the PP, as opposed to between the SUP and the PP. This is largely different in Universities B and C, in which this relationship is more linear and the choice of the SUP, in addition to choosing explicit values, objectives, and expected results, becomes a choice of thematic areas on which to work pragmatically.

In University A, as the former Rector states in the prologue to the formulation document, “the university has gone beyond the regulatory wanted to formulate a Strategic Plan to clearly define the values in which it believes, its mission values in which it believes, the mission it has set itself and, above all, its vision and related objectives, the strategies to achieve them and the necessary actions the necessary actions”. In University B, although the methodological value of the preamble to the SUP explains the articulation of the components, the document immediately focuses on the three main areas (teaching, research, and third mission). In University C, the drafting methods, while providing an explicit methodological basis, identify various strategic lines, similar to University A.

5.3 Linking strategic planning with performance management in the three cases

From the analysis of the data gathered through the documentary analysis and the interviews, it is possible to attempt to identify a link between strategic planning and performance management systems in the three cases analysed, as well as with the allocation of financial resources.

In University A, as already mentioned, there is a kind of logical inversion between the two strategic planning documents, since the TYPD is a tool for implementing the SUP, through three-year actions. The opposite happens in University B, where the SUP is characterised as a document implementing the three-year strategic guidelines. Something different again happens in University C, where the SUP initially includes the previous triennial strategic guidelines, and at the same time, conversely, is the starting point to for defining subsequent ones.

In University A, the main document of the performance management cycle, the PP, refers to the TYPD. As the methodological document attached to the SUP indicates, “TYPD and PP can be consolidated into a single document that, while distinguishing the specific areas of intervention, leaves no doubt about their common starting point: the strategic ambition of the University” (Methodological attachment to the SUP 2012–2014, p. 3). The PP 2014–2016, therefore, explicitly refers to a cascading system between the SUP, the TYPD, and the PP, confirming, on the one hand, the regulatory obligation and, on the other hand, the need to link the planning of activities to the degree of response from the organisation in its various components. The TYPD represents, in terms of continuity and the cascading of objectives, the link between the strategic objectives defined by the SUP and the operational objectives of the individual organisational structures of the university identified by the PP. In other words, the PP is the tool for implementing the TYPD. The PP, structured on an annual horizon (despite having a three-year duration), constitutes the reference for measuring results and assessing organisational and individual performance.

Unlike the strategic planning documents, the PP is prepared by the administrative staff. In University A, the individual organisational structures are required to propose operational objectives indicating: (1) the reference strategy identified within the SUP; (2) the perspective within which the identified operational objective is placed, concerning the eight perspectives identified by the TYPD; (3) the process overseen by the structure to which the objective refers; (4) a brief description of the objective and expected results; (5) the proposed indicator and its valuation with respect to the expected value; and (6) the financial resources allocated to the pursuit of each operational objective. Subsequently, the objectives of the PP are linked to the individual perspectives of the TYPD, such as the internal structure, teaching, integration with the territory, internationalisation, personnel, research, sustainability, and students.

Focusing on the development of the performance management system and the link with the strategic planning system over time, the document’s structure has been kept almost unchanged. However, after 2015, the idea of a document with a solid operational connotation, respecting the three phases of the performance cycle, became more generally accepted. At the same time, an increasing need was perceived to develop, in a systemic way, the planning of administrative activities in terms of performance, transparency, and anti-corruption. In this context, since 2016, the new guidelines have introduced the IP. As declared by an interviewee: “The intention has always been to keep the Strategic Plan separate from the performance management instruments, so that the Integrated Plan would draw on the objectives set by the Strategic Plan, but could also have a life on its own. We are aware that sometimes in other public sector administrations the Strategic Plan coincides with the Integrated Plan.”

The performance objectives identified in the IP, which are operational, are strictly linked to the strategic objectives contained in the SUP. The process for their definition follows two stages. In the first phase, the structures propose transversal objectives, shared by two or more organisational units; in the second phase, the structure objectives are proposed (individual, i.e. associated with a single organisational unit). The performance goals are divided into organisational performance goals and individual performance goals. The process of evaluating organisational performance is hierarchical and starts from the evaluation of the university’s performance based on the evaluation of those indicators related to economic and financial sustainability, scientific productivity, and internationalisation. The organisational performance of the departments, schools, and research centres is measured considering indicators related to research, teaching, internationalisation, and management efficiency. The PR closes the cycle, using the indicators provided by ANVUR.

In University B, the PP, whose first issuing was in 2011, from 2016 also started including information relating to transparency and anti-corruption, becoming an IP. The reason for that can be found in the words of an interviewee: “The need to move from the PP to the IP derives from the need to avoid writing the same things in different documents or, vice versa, the risk of writing different things in the three documents (actually this has never happened in our university, since the documents were prepared by the same structure). Moreover, it is appropriate to have an IP because, in defining the managers’ objectives, they take into account different aspects (anti-corruption, transparency, efficiency).”

This document is essentially aimed at the central administration, albeit with references to the university’s entire activity. The IP is drawn up by the office managers and the GD, while the structure that coordinates the entire process is the personnel area management.

As highlighted before, the IP concerns the administrative sphere and is an expression of how the academic organisation pursues its management objectives and implements its functions, in support of the political bodies, in achieving the strategic objectives of teaching, research, and the third mission, as reported in the planning process. The preparation of the IP, therefore, starts from the basic guidelines contained in the TYPD and the SUP and then, through various meetings with managers and top management, they are translated into operational objectives, which are subsequently translated into actions, indicators, and targets based on which performance measurement, evaluation, and reporting is carried out. This is clearly represented in the performance tree, a tool which, in a “cascading” logic, “graphically represents the links between strategic priorities, general strategic guidelines and operational objectives” (IP 2020–2022, p. 15).

While there was no clear link between strategic planning and performance management cycle in the past, University B’s last IP now displays an explicit reference to the SUP. In particular, the GD’s objectives (and related actions) derive directly from the strategic objectives set out in the SUP, while the managers’ objectives derive, in turn, from those of the GD, and therefore only indirectly from the SUP.

Finally, the closing document is the PR. The PR is drawn up by the GD annually, following a specific format. This document makes it possible to highlight the organisational and individual results achieved in relation to the expected targets regarding the individual planned objectives and resources.

The approach described for the IP is also confirmed in this document, i.e. a comparison is made with the strategic planning documents and, in particular, with the monitoring of the SUP, as well as taking into account the report that the GD prepares at the end of each year on management activities.

As declared by the GD during a meeting of the BoD: “The IP has been really improved compared to the past, both in terms of editorial and content. This is thanks to the fruitful work of the managers involved. The IP demonstrates, in the best possible way, the ability to coherently correlate administrative activities with the planning policy documents adopted by the university […]. This document […] highlights the coherence between the university’s strategic planning system at the political level, the management activities, and the financial planning.”

In line with the regulations, University C planned also to adopt a system of performance evaluation in 2010 by issuing the first PP for the period 2011–2013. However, on the institutional website of the university, we found an archive where the first PP is the one dated 2013–2015, so we do not have any information about the very first PP, except for the fact it was based on the application of the Common Assessment Framework (CAF) model.

In this document, a performance tree highlights the logical roadmap, which links the institutional mandate, the mission, the strategic areas, the strategic objectives (with their indicators and targets), and the operational plan (which includes operational objectives, actors, and resources). In the first PPs, three different strategic areas were identified: didactics; research; and services (then named the “Executive Plan”). The latter includes the objectives assigned to the GD from which are derived the objectives to be assigned to each manager, in addition to those arising from the strategic planning documents. However, we did not find an explicit link between these objectives and those of the SUP; instead, the document seeks alignment between the performance cycle and the financial reporting planning cycle.

By comparing the different PPs, it emerges that the strategic objectives related to the three strategic areas have changed over time. Moreover, while the strategic areas of didactics and research are under the responsibility of the political bodies, the strategic area of the Executive Plan is under the responsibility of the GD who, also through the other managers, is responsible for the correct management of the organisation, as well as for verifying its effectiveness and efficiency.

Another crucial strategic objective is transparency, which is directly related to the performance of the administrative activity and the best use of public resources; therefore, the objectives of the PP are closely related to the strategic and operational planning of the administration and are considered strategic for the university itself.

In the process of identifying the areas of intervention, different actors have been involved: the political body; the Rector; the delegates of the Rector in the areas of strategic planning, didactics, and research; and the GD, who in turn consults the managers involved. In order to gather and analyse the data, the self-evaluation committee and self-evaluation support group are also involved. The 2013–2015 PP concludes with the desire to improve the process both by anticipating the preparation of the plan together with the budget, and by better involving stakeholders and all delegates and managers and sharing with more actors the actions and strategies to be implemented.

Similar to Universities A and B, in 2016, the PP became an IP. The IP is organised in five sections:

-

1.

The strategic framework of the university, where the main lines of development of the administrative activity are indicated, according to the strategic planning documents, the financial reporting planning documents, and the actions taken and to be taken.

-

2.

The organisational performance, which constitutes the central part of the IP, which lists the objectives of the planned actions, the related monitoring and measurement indicators, and all those involved in administrative performance.

-

3.

Analysis of risk areas, drawn up according to the guidelines provided by the Anti-Corruption Authority (ANAC), whereby the areas at risk of corruption are defined.

-

4.

Communication and transparency, which specifies the actions that the university intends to promote in order to meet the requirements of transparency and contains the communication plans aimed at informing stakeholders about the results achieved by the university.

-

5.

Individual performance, the last section of the plan, which describes the criteria that the university intends to adopt for the assignment of individual objectives, as well as for the evaluation and monetary incentives for technical-administrative staff.

In the IP 2016–2018, for the first time, an important attachment was added highlighting the links between the SWOT analysis and the SUP by creating a more direct link between strategic planning and performance management.

This link is strengthened in the IPs 2018–2020 and 2019–2022, where a specific section recalls the macro-objectives of the SUP and connects the strategic guidelines of the IP with them. The document explicitly states that, although the IP strategic guidelines do not precisely coincide in wording and number with those mentioned in the SUP 2016–2018, these strategic objectives derive from that document (IP 2018–2020, p. 12).

Further on in the document, it is reaffirmed that the link between the university’s strategies and the performance cycle is of fundamental importance: the relationship between strategic planning and performance management systems is expressed as a link between the university’s political perspective of development, set out in the SUP, and the management actions to be implemented to achieve the expected results, contained in the IP (IP 2020–2022, p. 17). As learned from an interviewee: “The university in the last years has introduced a new planning process which aims to maintain coherence between the operational dimension (performance), the dimension linked to access and usability of information (transparency), and the dimension linked to access to information (transparency). Moreover, the more recent IPs aim for greater consistency with the strategic planning system, in that the objectives of the performance planning are in line with, and derive from, the objectives of the strategic planning.”

As literature highlights (Bower & Gilbert, 2005; Francesconi & Guarini, 2018; Goh et al., 2015), evidence confirms that the strategic planning and the performance management dimensions are strongly connected with the resource allocation in all three cases. In University A’s budget, we read that its “formulation is carried out through a process in which the (strategic and operational) objectives of the University drive the resources allocation aimed at their achievement. It represents the translation of those strategic lines in monetary terms” (Annual and Three-Year Budget, p. 8). At the same time, in the IP, we found a link between the budget and the performance cycle. In fact, University A is trying to progressively optimise the allocation of its resources, by investing them in long-term projects that can have a positive impact on performance, to draw up a budget that is as consistent as possible with the strategies, following the circularity that characterises the strategic, financial, and operational planning phases.

As far as University B is concerned, on the one hand, the annual budget and the three-year budget (composed of the economic and investment budgets) are the technical and accounting tools through which the university’s strategic goals are set out in the short and medium term following the institutional mission of the university. Another important tool is represented by the activity budget, a document included in the explanatory note to the budget, through which strategic and operational goals are connected to the quantity and the quality of resources allocated to their achievement by highlighting the budget specifically earmarked for the pursuit of strategic actions and objectives. On the other hand, the IP represents the document by means of which performance is linked to the budget cycle. As it is clearly expressed: “The integration between the budget cycle and the performance cycle makes the Integrated Plan the means through which disclosing both the recommendations included in the strategic planning documents, as well as the initiatives aimed at improving the effectiveness and efficiency of the University’s management processes” (IP, p. 3). Coherently, the IP depicts the amount of budgetary resources necessary to achieve the operational objectives, as determined in the planning phase.

Turning to University C, both the documentary analysis and the interviews revealed the willingness to make the budget increasingly consistent with the strategic objectives provided by the governance, through a path of integration and circularity between the strategic planning and the budgeting processes aimed at enhancing the quality and efficiency of services, with a view to continuous improvement. This connection was still partial during the years under investigation; however, an interviewee stated that: “In the next years, we intend to draw up a road map to define the timing of all operational activities, also for a gradual coordination between budget and objectives, towards an alignment of the two planning processes phases”. Conversely, a similar path has been traced to increasingly link resource allocation to performance. In fact, as scholars have also identified in other cases (Van Dooren et al., 2010; Van Thiel & Leeuw, 2002), University C has started a performance budgeting system, by identifying specific financial resources for all the GD’s objectives from 2017 onwards. Moreover, the internal distribution of resources to departments is based on the results achieved, with a budget allocation policy based on awards and other selective criteria.

In all three universities, we therefore notice that the integration between strategic planning and performance management systems is an ongoing process that is being improved over time. Evidence demonstrates the willingness of these universities not only to meet regulatory requirements, but also to implement the logic of planning, both at political and administrative levels, to promote the proper functioning of the academic organisation, with a view to improving decision-making processes and accountability towards its stakeholders. However, while strategic planning information is incorporated in the performance management system, the role that performance management systems play in redefining strategies is less evident.

6 Discussion and conclusions

The comparative analysis of the multiple case studies carried out in Section 5, although without making any claims regarding generalisability, provides interesting food for thought on how strategic planning is conceived by universities, how the process to define strategies is developed and connected with the operational documents and budget, and to what extent the strategic planning system can be integrated with the performance management system, overcoming semantic boundaries and capturing the implicit links.

Moreover, the interviews with some of the main actors involved in the two systems help to understand also the reasons underpinning certain political and administrative choices. Table 2 summarises our findings across the three case studies, as detailed in Section 5.

Concerning the strategic planning system, evidence demonstrates that, as Boyne and Walker (2010) claimed, the definition of the strategies is a process that is more effective the more it results in a shared and collective effort towards a common vision.

This is more likely to happen in those public organisations where the unitary strategy is the synthesis of different strategic visions, linked to heterogeneous contexts and needs. Universities, embracing several areas of teaching, specialisation, and research, fall into this situation. In addition, the decision-making processes at universities are often complicated and extended due to the involvement and different interests of academic structures composed of professors and administrative staff.

Examining the three cases, a core aspect is the degree of participation of different actors involved in the process. While for University B the elaboration of the SUP is mainly delegated to the Vice-Rectors, who probably only informally consult the GD, in University A and University C, it appears to be more participatory and formalised. In fact, in University A, the project team involves different stakeholders in the process (including their competitors) through sharing the strategic ambitions of the governance bodies. This was mainly observed in the first wave of strategic planning. In the second wave, the phenomenon was scaled down, also in terms of participation, to make way for a more apparently centralised vision, but less impactful than the previous one. In University C, different political and administrative actors are involved in defining the areas of strategic intervention: the political body; the Rector; the delegates of the Rector in the areas of strategic planning, didactics, and research; and the GD, who in turn consults the other managers involved. During this time, University C has experienced better involvement from stakeholders and managers, and shared the actions and strategies to be implemented with more actors.

Moreover, University B has apparently not used external consultants, and neither has University C. University A, however, in the drafting of the second SUP, turned to external parties for various specific aspects (definition of strategic positioning and internationalisation strategy).

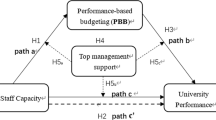

Therefore, three different patterns emerge, which can be placed along a spectrum ranging from University B, through University C, to University A. For example, University B still wants to maintain a clear distinction between the political and administrative sphere, and the strategic planning process involves only internal actors and only at the political level. University C, still maintaining the process as entirely internal, is instead trying to make a collective effort to bring both the political and administrative spheres of the university together towards common goals. The latter formalises a process in which participation is the widest, even involving external stakeholders.