Abstract

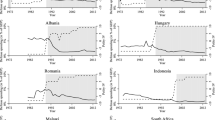

We explore how institutional set-ups, in particular changes in political institutions through coups d’état, can affect the way military expenditures are determined. We use a counterfactual approach, the synthetic control method, and compare the evolution of the military burden for 40 countries affected by coups with the evolution of a synthetic counterfactual that replicates the initial conditions and the potential outcomes of the countries of interest before exposure to coups. Our case studies suggest that successful coups result in a large increase in the military burden. However, when no effects or a decrease in the defense burden are found, it is often the consequence of a democratization process triggered by the coup. These results are in keeping with recent theoretical developments on the bargaining power of the military in authoritarian regimes. Failed coups, by contrast, produce a smaller, and mostly positive, effect on the military burden, possibly as a result of the incumbent’s strategy to avert further challenges to the stability of the regime by buying off the military.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The military burden in times of peace varies from zero (e.g. Costa Rica) to less than 0.2 % (e.g. Haiti, Panama or Iceland) to more than 14 % of the GDP (e.g. Saudi Arabia). In times of war the military burden can exceed a nation’s entire GDP (e.g. Kuwait).

Acemoglu et al’s study joins traditional theories of the incentives and constraints faced by all dictators who wish to remain in power (see, e.g. Kurrild-Klitgaard 2000; Crespo Cuaresma et al. 2011; Wintrobe 2012). Tullock (2005) offers a seminal and masterful scientific analysis of dictatorships and individual behaviour under autocracy by means of a rational choice model.

We thank an anonymous referee for suggesting this caveat.

In those cases, the weight is often negligible (e.g. in constructing Pakistan’s counterfactual, the algorithm assigned a weight of 0.001 to India).

Note that existing connections between countries, such as ethnic or political ties, may also cause military spending in one country to be affected by a coup in a non-neighboring country. Yet, links between countries may be multiple and often difficult to measure.

See Leon (2014) for a survey of the literature on the economic causes of coups.

According to our dataset, the average duration of a military regime is less than eight years. Marinov and Goemans (2013) combine two datasets to cover 249 distinct coup spells in 164 countries between 1945 and 2004 and find that the average duration of a spell is around eight years. Seven years is a safer choice for two reasons: first, the accuracy of this method in predicting the counterfactual level of military burden declines as we move away from the coup year; second, the longer the duration of a spell, the more likely a new regime change will occur. The military burden may then be affected by expectations of a soon-to-come regime change.

The root mean square predicted error (RMSPE) measures the pre-treatment fit between the path of the outcome variable for any particular country and its synthetic counterpart. The lower is the RMSPE the better is the fit.

We make an exception to this rule and consider the attempted coup in Venezuela in 2002, as we deem it an informative case.

Given the limits on the length of the article, we do not include the tables for the remaining cases, but make them available in the online appendix on the authors’ webpages (www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/people/bove/ and https://sites.google.com/site/rnistico/home).

To avoid cluttering the figures, we do not show experiments with a pre-treatment Root Mean Squared Prediction Error (RMSPE) twice that of the treated country.

To submit our results to a further robustness check, we have also run a panel data analysis, in particular a number of difference-in-difference estimations, and use three different types of treatments: successful coups, failed coups, and regime changes unrelated to coups. We look at the seven-year window following the coup. Results show that, on average, successful coups tend to increase the military burden, while both failed coups or other types of regime changes do not have any significant effect. This is consistent with most of our findings. Due to space limitations these data are not presented here, but are shown in the Online Appendix.

References

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2010). Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of california’s tobacco control program. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105(490), 493–505.

Abadie, A., & Gardeazabal, J. (2003). The economic costs of conflict: A case study of the basque country. The American Economic Review, 93(1), 113–132.

Acemoglu, D., Ticchi, D., & Vindigni, A. (2010). A theory of military dictatorships. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2(1), 1–42.

Aizenman, J., & Glick, R. (2006). Military expenditure, threats, and growth. Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 15(2), 129–155.

Albalate, D., Bel, G., & Elias, F. (2012). Institutional determinants of military spending. Journal of Comparative Economics, 40(2), 279–290.

Alptekin, A., & Levine, P. (2011). Military expenditure and economic growth: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Political Economy, 28(4), 636–650.

Besley, T., & Robinson, J. A. (2010). Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Civilian control over the military. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8(2–3), 655–663.

Bove, V., & Nisticò, R. (2014). Military in politics and budgetary allocations. Journal of Comparative Economics. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2014.02.002.

Bratton, M., & Van de Walle, N. (1994). Neopatrimonial regimes and political transitions in Africa. World Politics, 46(04), 453–489.

Brauner, J. L. N. (2012). Military spending and democratization. Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy, 18(3), 1–9.

Cotet, A. M., & Tsui, K. K. (2013). Oil and conflict: What does the cross country evidence really show? American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 5(1), 49–80.

Crespo Cuaresma, J., Oberhofer, H., & Raschky, P. A. (2011). Oil and the duration of dictatorships. Public Choice, 148(3–4), 505–530.

Dixit, A., Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1997). Common agency and coordination: General theory and application to government policy making. Journal of Political Economy, 105(4), 752–769.

Dunne, J. P., & Perlo-Freeman, S. (2003). The demand for military spending in developing countries: A dynamic panel analysis. Defence and Peace Economics, 14(6), 461–474.

Dunne, J. P., Perlo-Freeman, S., & Smith, R. P. (2008). The demand for military expenditure in developing countries: Hostility versus capability. Defence and Peace Economics, 19(4), 293–302.

Dunne, J. P., & Smith, R. P. (2010). Military expenditure and granger causality: A critical review. Defence and Peace Economics, 21(5–6), 427–441.

Dunne, J. P., Smith, R. P., & Willenbockel, D. (2005). Models of military expenditure and growth: A critical review. Defence and Peace Economics, 16(6), 449–461.

Geddes, B., Wright, J., & Frantz, E. (2012). Authoritarian regimes: A new data set. http://dictators.la.psu.edu/pdf/gwf-code-book-1.1.

Goldsmith, B. E. (2003). Bearing the defense burden, 1886–1989 why spend more? Journal of Conflict Resolution, 47(5), 551–573.

Hewitt, D. (1992). Military expenditures worldwide: Determinants and trends, 1972–1988. Journal of Public Policy, 12, 105–152.

Huntington, S. P. (1995). Reforming civil–military relations. Journal of Democracy, 6(4), 9–17.

Imbens, G., & Wooldridge, J. (2009). Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(1), 5–86.

Kollias, C., & Paleologou, S.-M. (2013). Guns, highways and economic growth in the United States. Economic Modelling, 30, 449–455.

Kurrild-Klitgaard, P. (2000). The constitutional economics of autocratic succession. Public Choice, 103(1–2), 63–84.

Landau, D. L. (1993). The economic impact of military expenditures (Vol. 1138). Oklahoma: World Bank Publications.

Leon, G. (2014). Loyalty for sale? Military spending and coups detat. Public Choice, 8, 1–21.

Looney, R. E., & Frederiksen, P. C. (1990). The economic determinants of military expenditure in selected east asian countries. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 11(4), 265–277.

Maizels, A., & Nissanke, M. K. (1986). The determinants of military expenditures in developing countries. World Development, 14(9), 1125–1140.

Marinov, N., & Goemans, H. (2013). Coups and democracy. British Journal of Political Science, 42, 1–27.

Mbaku, J. M. (1991). Military expenditures and bureaucratic competition for rents. Public Choice, 71(1–2), 19–31.

Nannicini, T., & Ricciuti, R. (2010). Autocratic transitions and growth. CESifo working paper.

Nordhaus, W., Oneal, J. R., & Russett, B. (2012). The effects of the international security environment on national military expenditures: A multicountry study. International Organization, 66(03), 491–513.

Nordlinger, E. (1977). Soldiers in politics: Military coups and governments. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Pesaran, M.H., & Smith, R. (2012). Counterfactual analysis in macroeconometrics: An empirical investigation into the effects of quantitative easing. IZA Discussion Paper, p. 6618

Pieroni, L. (2009). Military expenditure and economic growth. Defence and Peace Economics, 20(4), 327–339.

Powell, J. (2012). Determinants of the attempting and outcome of coups d’etat. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 56(6), 1017–1040.

Powell, J. M., & Thyne, C. L. (2011). Global instances of coups from 1950 to 2010 a new dataset. Journal of Peace Research, 48(2), 249–259.

Przeworski, A., & Limongi, F. (1993). Political regimes and economic growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7(3), 51–69.

Russet, B., & Oneal, J. (2001). Triangulating peace. New York: WW Norton & Company.

Smith, R. (1995). The demand for military expenditure. Handbook of Defense Economics, 1, 69–87.

Smith, R. P. (2009). Military economics: The interaction of power and money. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tullock, G. (2005). The social dilemma: Of autocracy, revolution, coup d’état, and war. (Selected Works of Gordon Tullock, Vol. 8). volume 8. Liberty Fund Inc., Indianapolis.

Whitten, G. D., & Williams, L. K. (2011). Buttery guns and welfare hawks: The politics of defense spending in advanced industrial democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 55(1), 117–134.

Wintrobe, R. (2012). Autocracy and coups d’etat. Public Choice, 152(1–2), 115–130.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Emanuele Ciani, Claudio Deiana, Leandro Elia, Ludovica Giua, Tommaso Oliviero, Matthias Parey, David Reinstein, Ron Smith, Alberto Tumino, Tiziana Venittelli and participants at the 2014 Annual Conference of the Royal Economic Society and at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the European Public Choice Society for their helpful comments. We also thank three anonymous referees for their constructive comments. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bove, V., Nisticò, R. Coups d’état and defense spending: a counterfactual analysis. Public Choice 161, 321–344 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-014-0202-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-014-0202-2