Abstract

This paper investigates the effects of public child care availability in Italy in mothers’ working status and children’s scholastic achievements. We use a newly available dataset containing individual standardized test scores of pupils attending the second grade of primary school in 2009–2010 in conjunction with data on public child care availability. Our estimates indicate a positive and significant effects of child care availability on both mothers’ working status and children’s Language test scores. We find that a percentage change in public child care coverage increases mothers’ probability to work by 1.3 percentage points and children’s Language test scores by 0.85 percent of one standard deviation; we do not find any effect on Math test scores. Moreover, the impact of a percentage change in public child care on mothers’ employment and children’s Language test scores is greater in provinces where child care availability is more limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

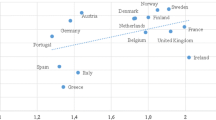

Data from Eurostat referred to 2009.

According to data from OECD Family Database for 2005, public expenditure on child care and early education services in Italy is equivalent to 0.6 % of GDP, while this figure for France, Sweden and Denmark is higher than 1 % (OECD 2010).

To date, in Italy there are 8,092 municipalities in 20 regions.

Law N. 285/1997 established a National Fund for Early Childhood and Adolescence allowing also the private and third sectors to provide child care services, while Law 448/2001 (Budget Law 2002) defined formal child care as “structures aimed at granting the development and socialization of girls and boys aged between 3 months and 3 years and to support families and parents with young children”.

National Law 104/1992.

We thank an anonymous referee for suggesting this methodology.

The INVALSI wave 2009–2010 that we are using actually contains a question regarding individual child care attendance during infancy. However, this information cannot be used in a credible manner, since it is characterized by almost 40 % of missing values.

In Italy there can be three types of child care provision: the first one refers to the cases where the public entity (i.e, the municipality) is both the owner and the provider of the service; the second, instead, refers to the cases where the municipality is the owner of the facility but outsources the provision of the service to other private entities; finally, there may be some cases where the private sector is both the owner and the provider of the service. For this analysis we use data concerning the first type of management.

The other official sources of information on child care coverage at aggregate level are ISTAT (Italian National Statistical Institute) and Istituto Degli Innocenti, but both provide information only at regional level for the period relevant for this study.

The dummy variable “Child missing information” indicates whether a child’s gender or citizenship is not available in the data; the dummy variable “Family missing information” is equal to one if a mother’s or a father’s employment or education are missing.

Concerning the estimation on mothers’ working status, results do not differ using probit or logit instead of OLS and GLS. Results are available upon request from the authors. When estimating the mothers’ work equation with OLS and GLS we also correct the standard errors for heteroskedasticity.

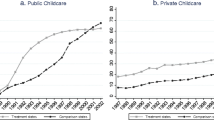

We assume that one more public child care center corresponds, on average, to 0.5 private child care center.

We also performed a robustness check (not reported here) excluding provinces in the Emilia Romagna region, which is characterized by very high child care availability with respect to other regions and with respect to the Italian average. Results are very close to the ones presented in Table 6, panel (c).

INVALSI data provide information on whether the child is regular in his school path or held back before or enrolled in a higher grade with respect to children of the same age.

References

Antonelli, M. A., & Grembi, V. (2010). The more public the more private? The case of the Italian child care. CREI WP No 3.

Baker, M., Gruber, J., & Milligan, K. (2008). Universal child care, maternal labour supply and family well-being. Journal of Political Economy 116(4), 709–745.

Becker, G. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (1st ed.). Boston, MA: University of Chicago Press

Berlinski, S., Galiani, S., & Gertler, P. (2009). The effect of pre-primary education on primary school performance. Journal of Public Economics 93, 219–234.

Berlinski, S., Galiani, S., & Manacorda, M. (2008). Giving children a better start: Preschool attendance and school-age profiles. Journal of Public Economics 92, 1416–1440.

Blau, D., & Currie, J. (2006). Pre-school, day care, and after-school care: Who’s minding the kids? In E. A. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education (Vol. 2).

Bratti, M., Del Bono, E., & Vuri, D. (2005). New mothers ’s labour force participation in Italy. LABOUR, 19, 79–121.

Carneiro, P., & Heckman, J. J. (2003). Human capital policy. In J. J. Heckman, A. B. Krueger & B. M. Friedman (Eds.), Inequality in America: What role for human capital policies? (pp. 77–239). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cascio, E. (2009). Maternal labor supply and the introduction of kindergarten in American public schools. Journal of Human Resources 44, 140–170.

Cittadinanzattiva. (2007). Gli asili nido comunali in Italia, tra caro rette e liste d’attesa: Dossier a cura dell’Osservatorio Prezzi e Tariffe di Cittadinanzattiva. Rome: Cittadinanzattiva.

Cunha, F., Heckman, J., Lochner, L., & Masterov, D. (2006). Interpreting the evidence on life cycle skill formation. In: Hanushek, E. A. & Welch, F. (Ed.), Handbook of the economics of education (pp. 697–812). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Datta Gupta, N., & Simonsen, M. (2012). The effects of type of non-parental child care on pre-teen skills and risky behavior. Economics Letters 116(3), 622–625.

Del Boca, D. (2002). The effect of child care and part time opportunities on participation and fertility decisions in Italy. Journal of Population Economics 15(3), 549–573.

Del Boca, D., & Pasqua, S. (2010). Esiti scolastici e comportamentali, famiglia e servizi per l’infanzia. FGA Working Paper No 36/2010.

Del Boca, D., Pasqua, S., & Pronzato, C. (2009). Motherhood and market work decisions in institutional context: A European perspective. Oxford Economic Papers 61(Suppl. 1), i147–i171.

Del Boca, D., & Vuri, D. (2007). The mismatch between employment and child care in Italy: The impact of rationing. Journal of Population Economics 20(4), 805–832.

EU (2002). Presidency conclusions. Barcelona European Council March 15 and 16, 2002.

Fitzpatrick, M.D. (2008). Starting school at four: The effect of universal pre-kindergarten on children’s academic achievement. BE Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 8(1 (Advances)), 1–38.

Havnes, T., & Mogstad, M. (2010). Is universal child care leveling the playing field? Evidence from non-linear difference-in-differences. IZA Discussion Paper No 4978.

Havnes, T., & Mogstad, M. (2011a). Money for nothing? Universal child care and maternal employment. Journal of Public Economics 95(11–12), 1455–1465.

Havnes, T., & Mogstad, M. (2011b). No child left behind: Subsidized child care and children’s long-run outcomes. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 3(2), 97–129.

Heckman, J. J., Stixrud, J., & Urzua, S. (2006). The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. Journal of Labor Economics 24(3), 411–482.

INVALSI. (2011). Rilevazione degli Apprendimenti—SNV Prime Analisi A.S. 2009/2010. Istituto Nazionale per la Valutazione del Sistema Educativo di Istruzione e di Formazione.

ISTAT. (2010). L’offerta comunale di asili nido e altri servizi socio-educativi per la prima infanzia. Anno Scolastico 2008/2009. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica.

Istituto Degli Innocenti. (2006). I nidi e gli altri servizi educativi integrativi per la prima infanzia. Rassegna coordinata dei dati e delle normative nazionali e regionali al 31/12/2005. Quaderni del Centro Nazionale di Documentazione e Analisi per l’Infanzia e l’Adolescenza n. 36.

Loeb, S., Bridges, M., Bassok, D., Fuller, B., & Rumberger, R. W. (2007). How much is too much? The influence of preschool centers on children’s social and cognitive development. Economics of Education Review 26, 52–66.

Melhuish, E., Sylva, K., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., Taggart, B., Phan, M., et al. (2008). Preschool influences on mathematics achievement. Science 321, 1161–1162.

OECD. (2007). PISA 2006 science competencies for tomorrow’s world.

OECD. (2010). OECD family database. Available at http://www.oecd.org/els/social/family/database.

Pavolini, E., & Arlotti, M. (2013). Growing unequal: Child care policies in Italy and the social class divide. Mimeo University of Macerata.

Pronzato, C. (2009). Return to work after childbirth: Does parental leave matter in Europe? Review of Economics of the Household 7, 341–360.

Ruhm, C. (2004). Parental employment and child cognitive development. Journal of Human Resources XXXIX, 155–192.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from Collegio Carlo Alberto (project “Parental and Public Investments and Child Outcomes”) and from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement no. 320116 for the research project FamiliesAndSocieties. We would like to thank Christopher Flinn, Cristian Bartolucci, Ignacio Monzon, Francesco Figari, Mario Pagliero, Vincenzo Galasso, Daniela Vuri, Elena Meschi, Claudio Lucifora, Marco Francesconi, Chiara Monfardini and Silvia Pasqua and seminar participants at DONDENA (Bocconi University), CHILD and 4th IDW (Collegio Carlo Alberto), NYU, CHILD-RECENT (University of Modena) and the Catholic University Milan for useful suggestions and comments. We also thank the editor and two anonymous referees for their helpful suggestions. We are also grateful to Piero Cipollone (Bank of Italy) and Patrizia Falzetti (INVALSI) for providing the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brilli, Y., Del Boca, D. & Pronzato, C.D. Does child care availability play a role in maternal employment and children’s development? Evidence from Italy. Rev Econ Household 14, 27–51 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9227-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9227-4