Abstract

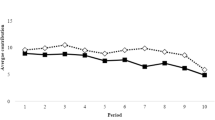

We experimentally study the effects of common fate on voluntary contributions to linear public goods. In each period, earnings are assigned to subjects according to the outcome of a lottery. In ‘common fate’, ‘independent fate’ and ‘rival fate’ treatments, the lottery outcomes of group members are (respectively) positively correlated, stochastically independent and negatively correlated. We observe the highest contributions and strongest reciprocity under common fate. Contrary to the game harmony hypothesis, contributions are not lower under rival fate than under independent fate. Surprisingly, under rival fate, having won the lottery in one period induces higher contributions in the next period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Ledyard (1995) for a survey of relevant results.

In 4/9 of cases in which an IF player is a winner, the two other group members are losers.

References

Bacharach M (2006) In: Gold N, Sugden R (eds) Beyond individual choice: teams and frames in game theory. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Bacharach M, Guera G, Zizzo DJ (2007) The self-fulfilling property of trust: an experimental study. Theory Decis 63:349–388

Battigalli P, Dufwenberg M (2007) Guilt in games. Am Econ Rev Pap Proc 97:171–176

Bolton GE, Ockenfels A (2000) A theory of equity, reciprocity and competition. Am Econ Rev 90:166–193

Bolton GE, Brandts J, Ockenfels A (2005) Fair procedures: evidence from games involving lotteries. Econ J 115:1054–1076

Brewer MB, Kramer RM (1986) Choice behavior in social dilemmas: effects of social identity, group size, and decision framing. J Pers Soc Psychol 50:543–549

Buckley E, Croson R (2006) Income and wealth heterogeneity in the voluntary provision of linear public goods. J Public Econ 90:935–955

Cookson R (2000) Framing effects in public goods experiments. Exp Econ 55:55–79

De Cremer D, Van Vugt M (1999) Social identification effects in a social dilemmas: a transformation of motives. Eur J Soc Psychol 29:871–893

Fehr E, Schmidt KM (1999) A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Q J Econ 114:817–868

Fischbacher U (2007) z-Tree: zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp Econ 10:171–178

Gold N, Sugden R (2007) Collective intentions and team agency. J Philos 104:109–137

Ledyard JO (1995) Public goods: a survey of experimental research. In: Roth A, Kagel J (eds) Handbook of experimental economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp 111–194

Lyubomirsky S, King L (2005) The benefits of frequent positive affect does happiness lead to success? Psychol Bull 131:803–855

Sugden R (2003) The logic of team reasoning. Philos Explor 6:165–181

Tan JHW, Zizzo DJ (2008) Groups, cooperation and conflict in games. J Socio Econ 37:1–17

Zizzo DJ, Tan JHW (2002) Perceived harmony, similarity and cooperation in 2 x 2 games: an experimental study. J Econ Psychol 28:365–386

Acknowledgments

We thank Michele Bernasconi, Luigino Bruni, Benedetto Gui and Sebastian Kube for useful comments. Financial support from the PRIN projects “Analysis of the Economic Effects of Interpersonal Relationships” and “Behavioral Approach to the Economic Analysis of Tax Evasion” are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Instructions of the experiment

[Instructions were originally written in Italian.]

[In all treatments]

Welcome! Thanks for participating in this experiment. By following these instructions carefully you can earn an amount which will be paid in cash at the end of the experiment. During the experiment you are not allowed to talk or communicate in any way with other participants. If you have any question raise your hand and one of the assistants will come to you to answer it. The following rules are the same for all participants.

1.2 General rules

The experiment consists of 25 periods. At the beginning of the experiment you will be randomly and anonymously assigned to a group of three subjects.

Of the other two subjects in your group you will know neither the identity nor the earnings. Finally, the composition of your group will remain unchanged during the 25 periods of the experiment.

1.3 How to determine your earnings

In each of the 25 periods you have to decide how to allocate an endowment of 100 tokens between a PRIVATE ACCOUNT and a COLLECTIVE ACCOUNT.

Each of the two accounts generates a return which is expressed in points. In particular:

-

each token allocated by you to the INDIVIDUAL ACCOUNT generates a return for you of 2 points;

-

each token allocated by you or by any other of the members of your group to the GROUP ACCOUNT generates a return for you and for every other member of your group of 1 point.

[In CF]

In each period, the returns generated by the two accounts will be assigned according to the outcome of a lottery. At the end of each period, one of three lottery tickets (numbered from 1 to 3) will be assigned to your group randomly and with equal probability. Then, the computer will select the winning ticket among the three tickets, randomly and with equal probability. If your group has the winning ticket, each member of your group will receive in that period the points generated by the two accounts. Otherwise, if your group does not have the winning ticket, none of your group will receive any of the points generated by the two accounts in that period.

At the end of each period, you will be shown three screens. In the first screen, you will see how many tokens you have allocated to the two accounts, the total number of tokens allocated by the members of your group to the GROUP ACCOUNT and the number of points generated by the two accounts before playing the lottery. In the second screen, you will be shown the ticket assigned to your group. Finally, in the last screen you will be shown the outcome of the lottery and the corresponding number of points obtained in the period.

[In RF]

In each period, the returns generated by the two accounts will be assigned according to the outcome of a lottery. At the end of each period, the computer will assign randomly and with equal probability one of three tickets (numbered from 1 to 3) to each subject of your group. Then, the computer will select the winning ticket among the three tickets, randomly and with equal probability. The holder of the winning ticket will receive in that period the points generated by the two accounts. The other subjects in your group will receive none of the points generated by the two accounts in that period.

At the end of each period, you will be shown three screens. In the first screen, you will see how many tokens you have allocated to the two accounts, the total number of tokens allocated by the members of your group to the GROUP ACCOUNT and the number of points generated by the two accounts before playing the lottery. In the second screen, you will be shown the ticket assigned to you. Finally, in the last screen you will be shown the outcome of the lottery and the corresponding number of points obtained in the period.

[In IF]

In each period, the returns generated by the two accounts will be assigned according to the outcome of a lottery. At the end of each period, the computer will assign randomly and with equal probability one of three tickets (numbered from 1 to 3) to you. Then, the computer will select the winning ticket among the three tickets, randomly and with equal probability. If you hold the winning ticket, you will receive in that period the points generated by the two accounts. Otherwise, if you do not hold the winning ticket, you will not receive any of the points generated by the two accounts in that period. Your lottery is indipendent from those of the other subjects in your group. Thus, each subject in your group will participate in a lottery the outcome of which, although determined on the basis of the same rules, is indipendent from those of the lotteries of the other subjects in your group.

At the end of each period, you will be shown three screens. In the first screen, you will see how many tokens you have allocated to the two accounts, the total number of tokens allocated by the members of your group to the GROUP ACCOUNT and the number of points generated by the two accounts before playing the lottery. In the second screen, you will be shown the ticket assigned to you. Finally, in the last screen you will be shown the outcome of the lottery and the corresponding number of points obtained in the period.

[In all treatments]

At the end of the experiment, the computer will select randomly and with equal probability one of the 25 periods. The points obtained in the selected period will be converted in Euros at the rate 10 points = 1 Euro. The corresponding amount will be paid to you in cash at the end of the experiment.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Corazzini, L., Sugden, R. Common fate, game harmony and contributions to public goods: experimental evidence. Int Rev Econ 58, 43–52 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-010-0111-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-010-0111-8