Introduction

Gambling and anti-gambling policies are often the terrain for intense and complex public debate. Local and national politicians, citizens, market players and non-profit organisations are all potential actors in the fundamental political confrontation over the values involved. Discussions in the scientific literature often mention morality policy, a notion which is arduous to define. The widely accepted scholarly opinion is that morality policies are those involving a controversial question of first principles or core values (Mooney Reference Mooney2001; Studlar et al. Reference Studlar, Burns and Cagossi2018). However, this definition does not fully apply to gambling.

We agree with Knill’s definition of morality policies as those where the “regulatory substance is closely related to public decisions over societal values” (Knill Reference Knill2013: 311). A specific policy may therefore be defined as involving morality in some countries and not in others, and be related to certain time periods, depending on the cultural environment. This approach is particularly fruitful because it allows scholars to identify a morality policy by assessing the pertinent cultural opportunity structures (COSs). According to Knill (Reference Knill2013: 312–314), COSs are “specific configurations of cultural value dispositions and their institutional representation (via established interest groups, social movements, religious organizations, the institutional relationship between state and churches, the existence of confessional parties) that define issue- or country-specific resources for social mobilisation”. Notably, scientific literature always refers to and applies COSs at the national level, and almost no attention has been paid to the multilevel nature of policymaking.

This aspect is of particular interest in Italy when investigating policy practices related to gambling due to the contrasting nature of the relevant legislation produced by the State and by the regional and municipal authorities. The product is often a liberalisation at the national level and a restriction at the local level. Our case study tests the idea that gambling in Italy is a latent morality policy (Knill Reference Knill2013; Euchner et al. Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013) and controls for the presence of favourable COSs. Drawing on the above premises, we ask whether gambling COSs in Italy differ at the national and local levels. Once the presence of favourable COSs has been identified, our main thesis is that an understanding of the framing process is essential in the identification of morality policies. We intend to ascertain if and where conflicts over principles occur in the public discourse. A set of questions arises in consequence: where are the morality frames located? Which debates are crucial in determining if a policy is framed as a morality policy? Is the debate at the national level sufficient or do we need to consider the variations at the local level?

This contribution proposes an advance in the theoretical definition of morality policies by combining the analysis of the COSs with a frame analysis stressing the multilevel aspect of modern policymaking – an approach that has not been previously proposed. We offer an empirical examination of the relationship between COSs and the exploitation of morality frames with a case study (gambling policy in Italy), providing relevant insights into the multilevel aspects of framing by showing how COSs have been activated at the local level but not nationally. Our studies point to a greater understanding of the multilevel nature of gambling policies, suggesting also that the exploitation of moral frames is easier at the local rather than the national level due to the wider range of political venues, the often more fragmented political systems and the greater degree of contact possible between a politician and the individual citizen.

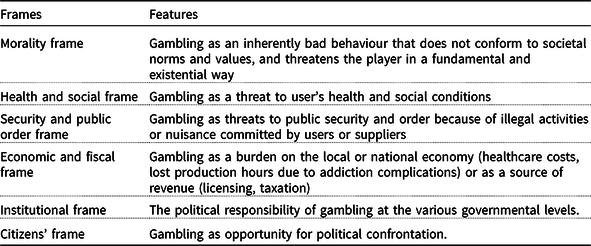

The article is divided into six sections. We begin with a literature review and focus on two main issues: the relationship between gambling and morality policy, and the role of COSs and frames in morality policies. “Case selection and methods” section explains our methodology and empirical material, together with the characteristics of gambling and morality policies in Italy, our terrain of investigation. In “Gambling COSs in Italy”, “Effects of COSs on framing” and “Framing gambling in Italy” sections, we discuss the findings, referring to the COSs related to gambling in Italy and presenting six categories for the framing of gambling in Italy: the morality frame, health and social frame, security and public order frame, economic and fiscal frame, institutional frame and the citizens’ frame. The conclusion returns to the research question and proposes an agenda for future research into gambling as a morality policy.

Literature review

Gambling and morality policy

Global gross gambling revenues – the amount gambled minus the winnings returned to players – have increased significantly in recent years (Sulkunen et al. Reference Sulkunen, Babor, Ornberg, Egerer, Hellman, Livingstone, Marionneau, Nikkinen, Orford, Room and Rossow2018b: 24–25). Although causal relationships have rarely been established, the main reason for this growth appears to be the increase in gambling opportunities (Sulkunen et al. Reference Sulkunen, Babor, Ornberg, Egerer, Hellman, Livingstone, Marionneau, Nikkinen, Orford, Room and Rossow2018b) produced mainly as a result of a further liberalisation of gambling policies (Adam and Raschzok Reference Adam and Raschzok2014). National policies, and regulations in consequence, are in general moving from restrictive to a more liberal approach (Adam and Raschzok Reference Adam and Raschzok2014), with the Norwegian case (Jensen Reference Jensen2017) providing an example of an exception to this trend. Scholars have focused on three major aspects of the phenomenon: addiction (Blaszczynski and Nower Reference Blaszczynski and Nower2002; Langham et al. Reference Langham, Thorne, Browne, Donaldson, Rose and Rockloff2016), policy change (Calcagno et al. Reference Calcagno, Walker and Jackson2010; Adam and Raschzok Reference Adam and Raschzok2014; Jensen Reference Jensen2017; Sulkunen et al. Reference Sulkunen, Babor, Ornberg, Egerer, Hellman, Livingstone, Marionneau, Nikkinen, Orford, Room and Rossow2018a) and morality (Ferraiolo Reference Ferraiolo2013; Euchner et al. Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013). The latter aspect is crucial to an understanding of the diffusion of more liberal policies, along with the presence of certain other conditions (Adam and Raschzok Reference Adam and Raschzok2014) including the presence of liberal gambling regimes in neighbouring jurisdictions, membership to the European Union and policy coherence. While these latter aspects are closely related to the policy processes, morality is also a societal issue.

Knill (Reference Knill2013) and Heichel et al. (Reference Heichel, Knill and Schmitt2013) have aided the identification of three conceptions of morality policies which emphasise either politics, framing or policy substance. Early studies on morality policies focused on the politics of morality rather than the policies per se (see Mooney Reference Mooney1999). This led to the identification of a new policy type (Mooney Reference Mooney1999) derived by morality politics (Haider-Markel and Meier Reference Haider-Markel and Meier1996), where policies are self-evident and unquestioned (Black Reference Black1974; Mooney Reference Mooney2001; Mooney and Schuldt Reference Mooney and Schuldt2008; von Herrmann Reference Von Herrmann2002; Ferraiolo Reference Ferraiolo2013). There is a focus on conflicts driven by religions (Engeli et al. Reference Engeli, Green-Pedersen, Larsen, Engeli, Green-Pedersen and Larsen2012b: 191). The authors hypothesise the existence of two religious worlds based on religious and secular party systems to explain morality policy processes.

A second approach (Mucciaroni Reference Mucciaroni2011: 211; Ferraiolo Reference Ferraiolo2013; Euchner et al. Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013) underlines morality policy rather than a policy per se as a strategy for framing policy issues. According to Mucciaroni, politicians, media and citizens typically frame policy issues using a rational-instrumental rationale, although issues may also be framed following a morality rationale. The choice relies heavily on the existing framing and the possibility of (political) gain from a moral rather than instrumental frame (Mucciaroni Reference Mucciaroni2011: 191).

A third perspective is that offered by Knill (Reference Knill2013: 311), who defines morality policies as those in which the regulatory substance deals with public decisions over socially shared values. The author distinguishes between manifest morality policies, latent morality policies and nonmorality policies (Knill Reference Knill2013: 312). This threefold approach is based not only on the relevance of the values, matched by COSs, but also on the distribution of costs and benefits among the various sectors of the population.

Conflict during the decision-making process as a result of an unavoidable debate on values is the main feature of manifest morality policies, which usually involve “life and death issues” such as abortion, euthanasia, artificial insemination, stem cell research and capital punishment, while economic costs and benefits are dispersed across different societal groups. Latent morality policies feature moral debates and “refer to issues in which value conflicts are not the order of the day, but – under certain conditions – might break out” (Knill Reference Knill2013: 313). The economic benefits are concentrated and costs are highly dispersed. Policies regarding sexual behaviours (e.g. homosexuality, prostitution, pornography) or addictive behaviours (e.g. gambling, drug use) are likely to possess latent morality traits. These policies are not inherently value based but can be read with a morality frame. Nonmorality policies, the last category, are those where values play no role. Knill (Reference Knill2013: 313) argues that “[w]hat distinguishes both manifest and latent morality policies from non-morality policies is their connectivity to value issues, or […] cultural opportunity structures”.

Morality policy: between COSs and frames

Knill’s threefold definition is particularly useful. It allows scholars to include information from the COSs present when determining whether or not an issue is a morality policy, rather than focusing on factors where religious beliefs play a crucial role such as death, reproduction and marriage (Engeli et al. Reference Engeli, Green-Pedersen and Larsen2012a). However, the task is far from simple. These sets of cultural value dispositions define the resources for social mobilisation over an issue in a specific country – resources that may be considered high for both manifest and latent morality policies but low for non-morality issues (Knill Reference Knill2013: 312–314).

What remains unclear, however, is whether the analyst is able to determine whether a social mobilisation actually happens, and whether a latent morality policy is exploited as a morality policy. Unless the issue of framing is addressed, the presence of favourable COSs does not imply moral debates because, according to Knill, the exploitation of values in a moral manner is in any case instrumental to power and economic gains (Reference Knill2013: 312–314). The possibility of this exploitation depends on the presence of favourable COSs, but COSs are solely a condition (Knill and Preidel Reference Knill and Preidel2015). Without proving the presence of morality framing, the presence of favourable COSs and dispersed interest do not necessarily indicate social mobilisation in the form of a debate over principles and values. Favourable COSs are a necessary but not sufficient condition for the exploitation of morality frames, and the two dimensions therefore need to be considered as theoretically distinct.

The first coherent and robust framework for the analysis of political frames was developed by Mucciaroni (Reference Mucciaroni2011: 194) who defined morality frames according to the key reference point of private, social or governmental behaviour. Ferraiolo (Reference Ferraiolo2013), in extending Mucciaroni’s analysis to lottery gambling in the USA, notes that politicians may present gambling within three different frames: (a) a rational-economic frame based on the idea that a policy is effective only if it produces the desired results, (b) a private morality frame when private behaviours are considered unnatural or sinful and (c) governmental morality frames when public officials promote “moral principles like justice, fairness, freedom, equality, order, and security” (Mucciaroni Reference Mucciaroni2011: 194). In a very similar fashion, Euchner et al. (Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013: 377–378) identify four frames in their analysis of German and Dutch gambling and drug policies: health and social, security and public order, economic and fiscal, and the morality frame. Although aspects of morality may exist within the first three frames, the instrumental aspects predominate in the reading.

Even though frame analysis is the key methodology exploited to assess the presence of morality policy, little agreement exists in the field as to where to look to detect the prevailing frames. Is a purely political debate, for example, within a parliamentary context, sufficient for the classification, or do we need to take a broader view? Moreover, given the multilevel nature of gambling policy, additional issues emerge regarding the local political or public debates. The multiple problems encountered in the face of the empirical evidence are both methodological and epistemological in nature. The core issue with the former concerns the difficulty in assessing the presence of moral frames used in the public and political debates. For example, both Mucciaroni (Reference Mucciaroni2011) and Ferraiolo (Reference Ferraiolo2013) deliberately focus on parliamentary debates, while Euchner et al. (Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013) limit their analysis to the “preambles or explanations of laws and on policy reports” (Euchner et al. Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013: 376). This methodological strategy has obvious drawbacks because it collapses the public debate into the formalised political debate. However, if we consider Mooney’s idea of citizen engagement (Reference Mooney2001) or Knill’s opinion of the capacity of the COSs to mobilise (Reference Knill2013), it is clear that the analysis should also focus on the public debate, and attention should be paid to the mobilisation capacities of the national, subnational and municipal political spheres.

The second limit of this approach in its application concerns the epistemological aspects of the moral frame. Most scholars have admitted that in many cases, instrumental frames coexist with moral frames (Mucciaroni Reference Mucciaroni2011: 198; Ferraiolo Reference Ferraiolo2013: 225; Euchner et al. Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013: 376), making it difficult to conclusively determine the presence of a moral frame. Moreover, scarce attention has been paid to what we nominate as the “paternalistic” frame. To quote Euchner et al. (Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013: 378), “gambling is not a normal economic market; the protection of the consumer is of central concern”. Notwithstanding the limitations noted above, we consider a frame approach oriented to the public debate at large to remain a useful tool and a reasonable option in assessing whether a latent policy may also feature the conflicts over values and first principles typical of true morality policies.

Case selection and methods

Our research question asks whether gambling policy decisions can be framed with reference to morality both at the national and local levels by determining the location of the morality frames. This section will first illustrate the reasons why Italy was chosen for the case study and follow with a presentation of the empirical material and the research and analysis methods used for the study.

Italy was selected as our terrain of investigation because it is a State which for several reasons represents a crucial environment for the study of gambling policies. In addition to being one of the largest gambling markets globally and an international landmark from a regulatory standpoint, the scholarly literature lacks an account of its specific case, which features a multilevel conflict over gambling.

In 2018, Italy recorded the highest gambling losses of any European State, with gross gambling revenue of €19 bn (ADM 2019: 79). It ranked fourth globally after the USA, China and Japan. Italy was ninth in the world for losses at just under $US400 per adult resident, half of which was spent in gaming machines not located in casinos (The Economist 2017).

Italian regulatory measures related to gambling are internationally unique (Rolando and Scavarda Reference Rolando and Scavarda2016). The evolution of the gambling industry in Italy has been described as a three-stage process likened to the growth of an organism (Pedroni Reference Pedroni2014; see also Croce et al. Reference Croce, Lavanco, Varveri, Fiasco, Meyer, Hayer and Griffiths2009 and Fiasco Reference Fiasco2010). During the “childhood” period (1946–1986), the State acted as guarantor of public safety with related restrictions on the gambling industry to reduce perceived risk factors. The introduction of offline and online games in the 1980s prompted an explosive growth in the gambling market and an unruly “adolescence” (1987–2011). The most recent and mature phase has featured a series of restrictive events and a call for responsibility. The Italian Law 189 of 2012 prohibited online gambling in public places nation-wide, introduced restrictions on gambling advertising to protect minors and recognised addiction to gambling as a pathology. In a parallel development, regional authorities and municipalities initiated measures against the proliferation of gambling, a move challenging both national legislation and the industry’s economic interests. The State currently maintains regulatory control over gambling. However, the activities are organised by private concessionaires within a competitive market. The State is thereby contemporaneously a monopolist and a promoter of a market which generates or favours excessive or pathological behaviours. Overall, the market in Italy has developed under internal budget constraints and Europeanisation pressures (Laffey et al. Reference Laffey, Della Sala and Laffey2016) in line with the convergence model identified by Adam and Raschzok (Reference Adam and Raschzok2014). However, both the regions and municipalities have in recent years followed the Norwegian example (Jensen Reference Jensen2017) and begun promoting restrictive regulation. Italy therefore represents not only an interesting case per se, and its specific multilevel conflict also aids in the discovery of a possible answer to the question left open by Jensen (Reference Jensen2017): does gambling have the potential to demonstrate a restrictive shift?

An empirical analysis of multilevel gambling policies presents us with a conundrum. Scholars have traditionally worked with parliamentary transcripts (Mucciaroni Reference Mucciaroni2011; Ferraiolo Reference Ferraiolo2013) or legal preambles (Euchner et al. Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013), an approach which has clear methodological drawbacks. A first complication is that it collapses the public debate into the political debate, with the later studied only via existing transcripts or other documentation. Additionally, local policymaking – often in the form of mayoral ruling – does not entail assembly debate or long preambles. We believe that an analysis should focus on the public debate. However, the difficulties involved in assessing any local public debate, which often occurs in the absence of dedicated press coverage, make this strategy impractical. The singularity and complexity of the phenomenon and the exploratory nature of the proposed research required a methodological approach capable of analysing the societal as well as the political debate, one examining the political interpretation through public statements and citizen intervention rather than limiting the sources to the official documentation.

The research is therefore based on a qualitative assessment of both the content analysis of interviews (as primary data) and of public documents (as secondary data). The choice of a qualitative framework based on interviews allowed the application of an actor-based interpretive paradigm (Corbetta Reference Corbetta2003: 14). We considered this specific qualitative approach to be particularly appropriate for the study of a phenomenon which has clear cultural relevance and which cannot, in our view, be reduced to a problem in a single category such as public order, health or fiscal matters, an impression which arises when the reading is limited to the legal preambles.

The application of an interview-driven qualitative approach could also aid our identification of cultural themes related to public gambling policy in Italy, a further goal of the study. Anthropological studies (Opler Reference Opler1945; Spradley Reference Spradley1979 among others) have demonstrated that qualitative research acknowledges cultural themes as a tacit premise constituting the basis of a person’s view of the world and as underlying much of their behaviour in the social sphere.

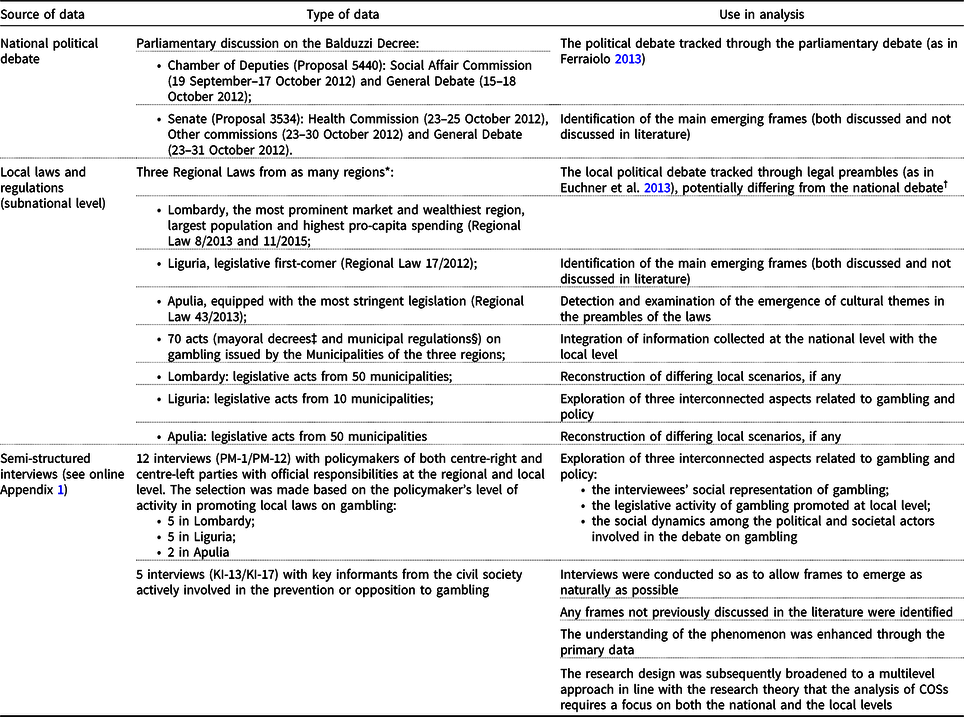

The literature on gambling was examined and the issues which appeared to relate to the Italian case were identified. The original empirical data were then collected from three main sources (see Table 1). These data were subjected to a content analysis through CADQAS software in order to create a coding system.

Table 1. Data sources

* The regions selected for the convenience sample were the locations of intense opposition to the proliferation of gambling documented in detail by the national press.

† The Italian Constitution allows subnational entities (regions and municipalities) to intervene in gambling matters as part of the concurrent State and local government responsibility for the health of their citizens. Municipal mayors also bear partial responsibility for local public order.

‡ Ordinanze del sindaco, urgent administrative acts issued by the Mayor and aimed at intervening in emergency situations.

§ Regolamenti comunali, ordinary regulatory acts issued by the Municipal Council and intended to norm a specific phenomenon such as local trade.

The analysis was conducted according to the grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss Reference Corbin and Strauss2015 because the method “stresses the importance of ‘discovering’ theory during the course of research” (Corbetta, Reference Corbetta2003: 246), allowing new and original issues to emerge, along with those already identified in the literature. A three-step coding process (online Appendix 2) was adopted for the analysis of the interview and document data. The transcribed documentation was read to identify any original terms and phenomena contained in the empirical material. The data were then grouped according to the first-order concepts. During the second phase, interconnected categories were grouped at a higher level of abstraction and second-order themes were identified through the relationships among first-order concepts. Several main aggregate theoretical dimensions were located, providing the basis for the discussion of the findings.

The parliamentary debates considered were three plenary sessions of the Chamber of Deputies (CoD) (Italian national parliamentary Lower House) (Chamber of Deputies 2012a, 2012b, 2012c), 13 meetings of the Welfare Commission of the CoD, 29 meetings of other Commissions of the CoD, 3 plenary sessions of the Senate or Upper House (Senata 2012a, 2012b, 2012c), 5 meetings of the Senate’s Health Commission and 10 meetings of other Senate Commissions. The analysis of secondary sources led to the identification of a series of frames compatible with those noted in the literature (Euchner et al. Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013): the morality, health and social, security and public order, and economic and fiscal frames (see “Framing gambling in Italy”). However, the grounded approach also revealed two further dimensions that have, to date, not been acknowledged in the literature. We labelled these new aggregate theoretical dimensions the institutional frame and the citizens’ frame. Both will be discussed below.

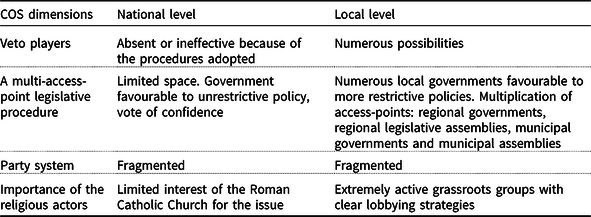

Gambling COSs in Italy

In our introduction, we presented COSs as both issue and country specific. However, little distinction has been noted after the seminal work of Knill between COSs pertaining to different issues within the same State. This section looks at the degree to which COSs may favour the formulation of restrictive gambling policies both at the national and local level, given that they are a necessary condition for the identification of manifest and latent morality policies. We shall first introduce the Italian-specific COSs in our study, moving to the issue-specific COSs at a later point, concluding with an attempt to isolate local COSs.

Several comparative studies have to date included Italy as a case study in their research (Knill and Preidel Reference Knill and Preidel2015; Studlar et al. Reference Studlar, Burns and Cagossi2013; Schmitt et al. Reference Schmitt, Euchner and Preidel2013). They implicitly or explicitly agree with the presence of favourable COSs for social mobilisation. Several (Knill and Preidel Reference Knill and Preidel2015; Studlar et al. Reference Studlar, Burns and Cagossi2013; Schmitt et al. Reference Schmitt, Euchner and Preidel2013) have noted that for every policy examined (same sex marriage, prostitution, etc.), the presence of veto players, a multi-access-point legislative procedure, the fragmented party system and the societal importance of the Roman Catholic Church are four aspects which contribute to any decisional gridlock. We assume that this is true for other COSs related to morality policies. Gambling as an activity offers a combination of concentrated economic benefits and highly dispersed costs, the usual profile seen in latent morality policies. However, little is about gambling-specific COSs in Italy because scholars have to date not studied the phenomenon. The issue specificity of COS should not be neglected. It has been demonstrated, for example, that the Roman Catholic Church has strenuously opposed certain morality policies such as euthanasia or abortion, but that its political stance on gambling is somehow more nuanced (Binde Reference Binde2007). According to Adam and Raschzok (Reference Adam and Raschzok2014: 4), the Roman Catholic Church has a “rather lenient stand on gambling and does not declare gambling to be a sin”.

Any discussion regarding the presence of favourable COSs in gambling in Italy therefore requires a discussion of the four country-specific dimensions noted above.

The presence of veto players and the existence of multiple possibilities to access the legislative procedure are two closely intertwined and related dimensions which differ at the national and at the local levels. The development of Italian national legislation on gambling featured, as noted above, a period of legislation in response to new technologies during the late 1980s to 2011. This was followed by the restrictive conditions imposed by the national Balduzzi Decree (189/2012). The Decree was presented by the Italian Minister of Health in the technocrat Monti government and agreed to by both the only party with a faith-based conservative profile – Berlusconi’s Popolo delle Libertà party (People of Freedom) – and the centre-left Partito Democratico (Democratic Party), the main progressive force in the Italian parliament. This specific genesis curbed the number of access-points to the legislative procedure and resulted in a streamlined parliamentary passage. The Monti Cabinet effectively controlled the path of the legislature through Parliament, and the possibility of any partisan veto was limited. The legislative proposal, part of a wider reform of the Italian health sector and lacking a particular focus on gambling issues, was reviewed by the Social Affairs Commission which made several amendments to the original norms, particularly to articles 1 and 4. The text referred consistently to health issues. The Decree was then presented in each of the legislative chambers, but the imposition of the vote of confidence in both chambers did not permit a full political debate nor the emergence of any backbencher opposition. Passage of the Decree required only a formal approval by the ruling majority and as a result, public debate of the issues connected to the legislation arose only after its approval as a national law.

Without the ability to play any major role at the national level, citizens seeking to restrain the growth of the gambling industry concentrated on an alternate political venue, and the push for a restrictive approach to public gambling moved to the local legislatures and regulators. In 2012, the Italian regional governments began to pass legislation on gambling aiming specifically to prevent compulsive gambling and to protect the consumer. Tax revenue potential had been a main driver in national-level political and legislative support of public gambling (Pedroni Reference Pedroni2014) and as a counter-argument to a call to curb the phenomenon. However, the regional governments do not benefit directly from the revenue gained from the expanding market for gambling. Any costs to the health services resulting from gambling pathologies are the responsibility of the regional authorities, and municipalities are required to fund the social consequences of local gambling with projects such as anti-poverty measures. After the first Regional Law was passed in Liguria, 18 Regions followed by promulgating their own rules on gambling. In 2018, Sardinia and Sicily became the last two Regions to present regional bills for consideration. The regional laws were issued by a variety of political coalitions and do not display any clear pattern. However, although it is not possible to describe here the COSs present in each Region, several general trends may be highlighted by taking into account the fragmented party system and the role of the Roman Catholic Church.

The Roman Catholic Church has always played a pre-eminent role in Italian politics, but the presence of the religious cleavage in the party politics altered after the mid-1990s, initiating a national shift from the religious to the traditionalist world. While the absence of a religious cleavage is a feature of a traditionalist world, it is also an environment where moral conflicts are intense and party-based (Hurka et al. Reference Hurka, Knill and Rivière2017: 14). Italy has featured a strong party system and religious cleavage for most of its history as a Republic (1945–1992). However, the collapse of the party system in the early 1990s also meant the decline in the importance of the principal parliamentary representative of the religious block, the Democrazia Cristiana party (Christian Democrats DC). This political upheaval brought about a significant change in the previously pre-eminent role the Roman Catholic Church had played in Italian politics. Silvio Berlusconi founded the Forza Italia party (Forward, Italy FI) in 1993 in an attempt to fill the new political vacuum with a party with a faith-based profile similar to that of the DC, but FI failed to achieve the strength of the DC. Minor DC parties continued to exist in the centre-right and centre-left “making morality issues a cause of internal disagreement in the blocs and sometimes also in the new political parties” (Engeli et al. Reference Engeli, Green-Pedersen and Larsen2012a: 189). The existence of these parties prompted the Monti Cabinet to employ the Italian vote-of-confidence tactic to ease the passing of the Balduzzi Decree.

The centre-left Partito Democratico (Democratic Party PD) and the centre-right Popolo della Libertà (People of Freedom PdL, founded after the collapse of Forza Italia) have generally expressed differing and contrasting views on public gambling. It is also important to note the recent formation of a “holy alliance” against gambling which crosses party lines, a coalition of the right-wing parties Lega Nord and Fratelli d’Italia (the Northern League and Brothers of Italy), the left-wing Sinistra Ecologia Libertà (Left, Ecology and Liberty) and the anti-elitist Movimento 5 Stelle (Five Star Movement). These smaller parties were not able to play more than a minimal role at the national level but could support the restrictive positions of ruling parties or take a restrictive stance at the local level once in government.

It should be noted that between 1987 and 2011, the Roman Catholic Church did voice some social concerns regarding the expansion of the gambling market (Dotti Reference Dotti2013) but with minimal emphasis and no moral stance, as expected (Binde Reference Binde2007; Adam and Raschzok (Reference Adam and Raschzok2014: 4). In view of this relative lack of activity, it should not be considered as a relevant actor influencing gambling. Religious confessions apart from the Roman Catholic Church play only marginal roles in Italy (Ozzano and Giorgi Reference Ozzano and Giorgi2016: 18–28) and are therefore also not considered active actors for gambling. However, the importance of the Catholic Church lies not only in its formal position. Italy is home to many organisations of Catholic inspiration which form an active part of the civil society, and their behaviours are driven by their affiliations (Bassoli Reference Bassoli2017; Ozzano and Giorgi Reference Ozzano and Giorgi2016: 180). The importance of this religious affiliation becomes clear when examining the key organisations in several fields including the media, nonprofit organisations and anti-gambling coalitions. Gambling has been heavily covered by only two mass media: a series of major local newspapers (GEDI group) and the monthly magazine Vita.it. While the former are nonreligious and discuss gambling issues at the local level in response to current political debates, the latter features an online section on gambling (Vita.it 2018b) with constant updates. The magazine is managed by over 60 NGOs, most of them of Catholic background (Vita.it 2018a). At the national level, the Associazione Movimento NoSLot (Anti-Slot Games Association AMNS) is a joint-venture between Vita magazine and a Catholic youth community organisation formally recognised by the Bishop of Pavia (NoSLot–AMNS 2018). Two other anti-gambling associations prominent in civil society are ALEA and the Movimento Slot-mob (Slot-mob Movement). ALEA was formed in 2000 by health professionals to study gambling, addiction and risk behaviours, and the health-related issues (ALEA 2000). The Movimento Slot-mob is the largest coalition of anti-gambling NGOs operating in Italy. It is supported by the Economy of Communion, an initiative of the international ecclesial and ecumenical Focolare Movement which proposes a religious inspired brotherhood for lay people (SlotMob 2018). The picture is different at a local level. Most grassroots actors operate as dispersed interest groups in their efforts to increase current restrictions on public gambling, and the most active groups are found in Lombardy and Campania. For example, a consortium of Catholic nonprofit organisations of the Benevento area in Campania promotes a specific municipal anti-gambling regulation through a project designed to create a network of “welcoming” communities in small towns (De Blasio et al. Reference De Blasio, Giorgione and Moretti2018). Similarly, the Movimento Slot-mob has advocated for more stringent local gambling regulations since 2015 (Int. KI-15). The latter movement – nationally coordinated – is very active in Latium (Rome) and Lombardy (Mantua, Milan). Lombardy is also home to AND (2019), one of Italy’s oldest and most well-known gamblers’ support associations, and the headquarters of AMNS (NoSLot–AMNS 2018).

Given the above contexts for COSs, it appears clear that moral actors (Knill Reference Knill2013) are strategic elements of the Italian public gambling sphere but also that their influence is not spread homogeneously across the levels. Notably, while the COSs are generally restrictive at the national level, the local spheres reveal COSs which are completely favourable (Interview KI-15) in areas where civil society seems more active, in particular in Campania and Lombardy. Table 2 summarises these findings.

Table 2. Italian COSs on gambling

Effects of COSs on framing

We have noted that favourable COSs are a necessary but not sufficient condition in identifying manifest and latent morality, and that therefore only an empirical analysis will shed light on the actual activation of morality frames in a given case. With this in mind, we will now investigate the presence of moral framing in the Italian context. Literature dealing specifically with Italian gambling policies is limited. Few scholars research gambling (Croce et al. Reference Croce, Lavanco, Varveri, Fiasco, Meyer, Hayer and Griffiths2009; Rolando and Scavarda Reference Rolando and Scavarda2018) and an approach able to even remotely assess existing frames is rarely adopted. An exception is the research conducted by Pedroni (2014, 2016, Reference Pedroni, Bray and Rzepecka2018) which focuses on media representations and highlights the element of personal security rewards promised by advertising promoting gambling with frames based on dreams, irony and myths. Pedroni (Reference Pedroni2014: 82) proposes that gambling be discussed using the four main rhetorics used by the media: the view of gambling as an expression of social subordination, the representation of the State as a cynical banker profiting from the weaknesses of citizens, gambling as an addiction and gambling as a phenomenon linked to crime (Interview KI-17). In contrast, the academic debate reveals a strong bias towards health issues (Croce et al. Reference Croce, Lavanco, Varveri, Fiasco, Meyer, Hayer and Griffiths2009; Jarre 2016, Reference Jarre2018), suggesting a predominance of “health and social frames” (Euchner et al. Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013) with a focus on the need to protect consumers and avoid addiction. The bulk of related literature concentrates on the same limited and related group of issues, above all that of addiction (Blaszczynski and Nower Reference Blaszczynski and Nower2002; Langham et al. Reference Langham, Thorne, Browne, Donaldson, Rose and Rockloff2016). This approach leads to an expectation, following a general trend towards instrumental frames as in other European countries (Euchner et al. Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013), that gambling is not framed as a morality policy in Italy.

Neither the Catholic Church nor its related organisations were able to effectively influence the formulation of the Balduzzi policies during the legislative process (Interview KI-16). While the need to tackle the health and societal issues was widely acknowledged by the public (Interview KI-17), the Law was not informed by Catholic organisations (Interviews KI-14, KI-15, KI-16), but rather by concessionaries (Interviews KI-17). An analysis of press articles from the period 2009 to 2012 reveals that the vast majority of the publications lacked a religious connotation before the passing of the Balduzzi Decree in 2012. The original text of the Law submitted for review to the Commission did foresee severe restrictions on the gambling industry. These limits were, however, “softened” before the approval of the final version when concessions were made in response to a lack of societal support and the need to balance health and economic budgets through gambling revenues (Chamber of Deputies 2012a, 2012b, 2012c; Senate 2012a, 2012b, 2012c). The changes were not the result of external pressures. After the Decree was passed, the press did not report any public statements by religious or private groups, and the existing secondary literature reveals no trace of indirect influence (Dotti Reference Dotti2013; Pedroni Reference Pedroni2014; Jarre Reference Jarre2016). The absence of their influence in this case is noteworthy, and the reason seems obvious. The approved norms were not decided by the Parliament, to which both the Roman Catholic Church and religious organisations would have had access, but by the Monti Cabinet and its technocrat Ministers and the comparatively insignificant parliamentary commission directly involved.

Catholic organisations are very active in promoting local legislation in Italy (De Blasio et al. Reference De Blasio, Giorgione and Moretti2018, Interview KI-15) and they play a crucial role in the creation of news and information. These same religious organisations are, due to their favourable positions, also the actors most likely to be able to move the moral debate from the national legislative sphere to a public or local context. The role of Catholic-related institutions in promoting, if not moulding, the debate on gambling becomes clear when we consider that almost half of the online debate on gambling has been published by the Magazine Vita.it (Interview KI-16).

Framing gambling in Italy

Employing the approaches described above, we intend in this section to present first the national debate, then the local level through legislative preambles, and conclude with an analysis of the qualitative interviews conducted with local policymakers.

An analysis of the parliamentary debate generated by the national Balduzzi Decree reveals that the greater part focused on health and social aspects (57% with 104 instances). The main influence on the debate was its broader purpose, a reform of the national health system. For example, a representative quote would be:

Regarding the update of the Essential Levels of Assistance, this is a measure which has been in the coming for years now, one which we have been unable to push through […] the topic of prevention has arisen, a fundamental in limiting and containing spending in new ways, and for which of course the solutions are probably not what we expected, what we wanted, we are well below [what we wanted], but we think it important that these innovations have been introduced. (Fontanelli, Chamber of Deputies 2012c: 64)

Notably, health aspects were juxtaposed to economic issues (tax revenues) (20%) or legislative responsibility (13%). The importance of the economic issue should not be underestimated, as shown in the recent literature (Jensen Reference Jensen2017). The issue constantly surfaced on its own or in juxtaposition with the health issue:

The contact with the Fifth Committee (Budget) has seen many dramatic moments, especially when it was understood that the Government had no intention to in any way to give up its revenues from gambling and therefore rejected interventions that had an explicitly deterrent effect (Binetti, Chamber of Depiìuties 2012c: 11).

It is most definitely an income that the State finds convenient, but the State cannot on the one hand fail to react to [the cause of] gambling pathologies and at the same time admit to the need for cure assistance (Palagiano, Chamber of Deputies 2012c: 54).

The co-occurrence of frames supported the importance of health as an issue, with 20 of the 36 economic frames coinciding with health frames. Clear morality frames were minimal (3%) and appeared only in the assembly debate (Table 3) with a minimal emphasis compared to other excerpts found in other contexts.

I would like to see a clear agreement in this Chamber that gambling is evil (Adinolfi, Chamber of Deputies 2012a: 35).

Table 3. Frames emerging from the parliamentary debate

Other features of the parliamentary debate were the issue of legality (4%) and questions regarding the appropriateness of the political venue, suggesting the importance of Mayoral activism (3%). However, the national debate was marked overall by the importance given to health and revenue issues.

The issue of legislative responsibility cannot be considered a full morality frame, as has occurred elsewhere (e.g. Ferraiolo Reference Ferraiolo2013), because here the main driver of the responsibility was the increase in gambling sites and possibilities which occurred between 1992 and 2012, a development encouraged by the State in order to boost tax revenues (Pedroni Reference Pedroni2014). This economic motive means that the responsibility frame was linked with the health and economic frames. Several previously foreseen restrictions on gambling sites were cancelled during the revision in an attempt to relieve national economic difficulties. This fuelled opponents’ criticisms regarding the “schizophrenic” nature of the Decree, which they felt introduced gambling addiction while stressing the importance of maintaining the levels of gambling-generated tax revenues.

Regarding gambling, removing important standards that had been approved in Commission XII [Social Affairs] means defending a minimal income today and not taking into account the thousands of Euros that have to be spent tomorrow to fight gambling addictions (applause from the members of the Democratic Party) and that is blindness (Miotto, Chamber of Deputies 2012b: 30).

Generalised and cumbersome Provisions which aim only to consolidate tax revenues and which leave citizens without any protection in the face of the damage caused by gambling and instant lotteries, representing a social problem for the weakest categories (Lauro, Senate 2012b: 11)

Italian regional laws and municipal acts do not generally feature a long introduction or preamble and usually commence with a short first Article explaining the rationale of the Act. In all the examined cases, the acts aimed to curb gambling possibilities via limitations on zoning or operating hours while supporting local trades and favouring the visibility of sites without electronic gambling machines. The division of financial, economic and administrative competencies between the State and the regional authorities leads here to a stress on health-related issues. Common measures formalised in the acts include fiscal incentives for commercial premises which abstain from providing gambling opportunities, minimum distance regulations regarding “sensitive” sites (such as schools, hospitals, churches, train stations), limitations on advertising and the institution of regional observatories on legal gambling. Regional legislation generally reinforced municipal regulations and obliged municipalities to identify further sensitive sites or, as in the case of Piedmont, limited the hours of operation. Local authorities in turn imposed further restrictions either as a result of the regional laws or municipal initiatives. Among the most cogent norms were the mayoral decrees defining hours of business as well as administrative closures for those infringing the norms, and fiscal leverage incentives for retailers without electronic gambling machines. All existing norms are based on health and social security considerations both in line with the Balduzzi Decree’s origins as a health-related act and with the political need to provide robust evidence of the urgency to intervene against the constitutional right of private entrepreneurship.

If the breadth of the analysis were confined to the relevant legislation, it might be valid to state that Italy is undergoing a long-term modernisation and secularisation process in line with the cultural shift model identified by Euchner et al. (Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013). However, a more in-depth analysis considering the views of decisionmakers and the frames they have deployed suggests a situation of greater complexity, particularly at the local level.

Our analysis identifies six main frames adopted by policymakers: (1) the morality frame; (2) health and social frame; (3) security and public order frame; (4) economic and fiscal frame; (5) institutional frame and (6) citizens’ frame. Of these, the first four clearly recall the work of Euchner et al. (Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013), while later two are idiosyncratic.

Politicians employing a morality frame present gambling as evil, and the distinction observed by Mucciaroni (Reference Mucciaroni2011) between “private behaviour morality frame” and “governmental morality frame” can be noted. The first is paternalistic, viewing the gambler as a social victim not responsible for their own behaviour, an injured party and subject of a social and moral crisis. The ludic dimension of gambling is refused completely and it is understood only as a condition that leads inevitably to moral ruin. Again, the morality is hidden in the rhetoric rather than explicitly expressed:

The cases that we read about in the newspapers, people leaving their kids in the car to go to gamble, taking days off or leaving work early to play, staying out all night. These are habits which clearly recall irrational behaviour patterns where gambling has become the reason for living (Interview PM-9).

The governmental morality frame considers gambling to be a phenomenon which State authorities must limit in order to protect the public, and that public authorities should never support nor gain from unhealthy behaviours. State authority action to counteract gambling’s most negative consequences – addiction or heavy financial losses – may also be understood as the results of a moral phenomenon. The text of one political document outlining the duty of administrators to build relationships with the health and policing authorities, Il Manifesto dei Sindaci a contrasto del gioco d’azzardo (Joint Mayoral Manifesto to Combat Gambling), is notable for its expressions of urgency and an excellent example of a governmental morality frame. According to the Manifesto, gambling “is destroying individuals, families, communities, … [it] produces suffering … alters the moral and social assumptions of Italians, substituting values based on work, effort and talent with gambling” (Legautonomie and Terre di Mezzo Reference di Mezzo2013).

Comments from interviewees tended to combine the health and social frames. While we expected health to be crucial, given the official framing exploited for legislative purposes, the absolutism came as a surprise. The interviewees appeared to consider the phenomenon relevant in quantitative terms. No clear numeric judgement was made, for instance, regarding the number of people supported by the Italian National Health Service as a result of gambling pathologies, but interviewees appeared convinced that the phenomenon had increased beyond measure and control. The most cited comparison was that of the heroin crisis during the 1980s, when young users were found dead in the public parks. Narratives to bolster this frame often denounced gambling as a social plague.

A friend who works at the drug abuse centre told me: “It is the same as with heroin in the 80s. The phenomenon exploded and we didn’t have the tools to deal with it, and we had to take care of the damage that it had created.” It is a social problem because the loneliness, the fragility of the people are social problems (Interview PM-2).

Similar descriptions can be found in the increased political content of administrative acts and regulations, for example, in the statements accompanying the approval of local laws where gambling is defined as a social epidemic requiring normative intervention at regional and national levels, and in municipal by-laws underlining the role of the Mayoral office as a bulwark against the spreading social ills of gambling. These by-laws often refer to epidemiological research and the social and economic risks of gambling, naming usury as one result. The Manifesto dei Sindaci cited above, adhered to by more than 250 municipalities including Milan and Rome, is further evidence of the impression that gambling must be “fought” at the local level.

Within the security and public order frame, gambling sites are described as places of discomfort and social disintegration synonymous with the degradation found in the worst areas of any urban community. Interviewees implied that the opening of a gambling establishment will transform and degenerate any district, devaluing the commercial worth of the surrounding proprieties.

Where there is gambling, there is always a threshold situation between degradation and public order. A neighbourhood with a gambling venue is seen objectively as having lost its attractions, a quality of life. Plus, there are all those people who are caught up in the problem or who are trying to escape it (Interview PM-3).

The idea of social then economic degradation is also found in the economic and fiscal frame. In addition to downgrading their local environments, gambling sites are cited as the cause of personal and family pathologies resulting in enormous financial burdens on the Italian public health systems which are administered and financed by local authorities and not by the national governments. Consistent with this frame is a narrative focused on the “poverty trap”. The interviewees often mentioned the importance of introducing, in the general principles of any legislation, the reminder of a duty to care for the less-advantaged, particularly for low income earners and the aged. A politician from the Lombardy Region provided an apt example:

Today, gambling has become a real drug. A drug that not only causes physical and mental damage to a person, but which also has economic implications for the person himself, for the household members, [and] for the community because the social and personal health cures have high costs (Interview PM-1).

The analysis of the interviews confirmed the relevance of the first four frames referred to above, the morality, health and social, security and public order, and economic and fiscal frames. However, the introduction of further frames was considered important for this case. In analysing Italian legislation, a range of levels of responsibility must be referred to. The hierarchy of political responsibility in Italy represents opportunities for diverse forms of positioning in the political arena at local to national levels. For example, while acts proclaimed by the State have aided the liberalisation of gambling nationally, regions and municipalities have introduced a series or regulatory policies aimed at restricting and controlling gambling in local public spaces. We propose an institutional frame to distinguish the roles of the various government levels. The Italian case makes it crucial to remember the difference in area responsibilities at the various governing levels. A further factor not considered by the four frames is the timing of regulations. In several relevant cases, local bodies had introduced legislation in the absence of or before a regional or national ruling, whereas other local governments adhered to the legislative framework formulated at a higher level.

Underlining the existence of this institutional frame could aid our understanding of the relevance of fragmentation among the social actors. A politician at the municipal level “besieged” with requests for institutional responsibility from the local citizenry must confront health, social and economic problems related to the liberalisation of gambling. The deregulation is the result of legislative decisions taken at a higher level and in response to contrasting arguments, for example, State legislation regarding the collection of tax revenues from gambling. Rhodes (Reference Rhodes2007) describes this as a classic governance problem within the context of the crisis of the nation-state. This institutional distinction between levels in the Italian governing hierarchy has emerged only since the 1990s during a long process of decentralization and devolution of powers favoring Regions and, partially, Municipalities. Another element relevant to the institutional frame is the presence of electoral campaign promises to promote anti-gambling policies. Local politicians legitimise their stance by claiming a greater sensitivity to the problem than that of national representatives, who are described as “far from the needs of citizens” and having “unclear relationships with the economic interests” (Int. PM3).

Municipalities are closer to people than [national] governments are. They are therefore able to understand aspects [of the gambling problem] which we have to have the courage and the imagination to take act on [in defence of the population] (Interview PM-8).

The second frame we propose for the Italian case is the citizens’ frame. It is closely related to the institutional frame but possesses a distinctive colouring. Politicians at the national level are perceived as distant from the public and more likely to further the economic interests of the gambling industry. Local politicians are able to present themselves as the political level closest to the citizens and their needs, the political voice with the social services and health concerns of the people at heart and their defenders in the “battle” against the national government. As self-appointed spokespersons for a broad and shared movement of anti-gambling opinion, local politicians present their challenge to gambling as “a political battle for the people” (Interview PM-3). The citizens’ frame may resemble a populist narrative; however, there are several notable distinctions: the opposition consists of the local people versus government, rather than citizen versus elite (Caiani and Graziano Reference Caiani and Graziano2016), and there is no clear instrumentalisation of diffuse public sentiments of anxiety and disenchantment (Betz Reference Betz1994: 4) and no legitimation of new political actors (Canovan Reference Canovan1999). The distinction appears clear in this excerpt:

The power of the gambling industry in every area, even political, is very potent. We have had the strength to pass a [regional] law against something as powerful as the gambling industry and those who earn from it. I think that is a very good thing (Interview PM-1).

Table 4 illustrates the six frames described above.

Table 4. Frames emerging from interviews with policymakers

Conclusion

We have noted in this article that gambling is often considered a morality policy (Studlar et al. Reference Studlar, Burns and Cagossi2018: 490). After a review of recent literature, we adopted the position of Knill (Reference Knill2013) and proceeded to discuss morality policies with reference to the COSs. We have identified the legislative hierarchy in Italy together with the nation’s capacity to generate a public debate on the issue to be a relevant terrain for the investigation of the economic and regulatory dimensions of gambling. The article shows the importance of moving from a national vision of COSs to a multilevel one. Our findings suggest that national and local legislation and the political and religious elements form a constellation of actors which is both instrumental – focusing on health-related issues and with no clear party cleavage – and moral. Our first specific contribution to the literature is to suggest the importance of applying a multilevel approach when studying morality policies, not only because national debate and local debates may be different but also because COSs are level specific as shown in Table 2.

The same applies to the framing issue. National frames and local frames are different. While we found evidence that a general trend towards a “normalisation” of gambling policy exists nationally, locally the policy is still framed morally. In other words, while the cultural shift model (Euchner et al. Reference Euchner, Heichel, Nebel and Raschzok2013) did fit the national debate given the significant stress on the health and economic frames, a more in-depth analysis of the local level suggested a strikingly different situation.

Evidence of a multi-faceted framing in gambling was established, with morality playing an important role either directly or indirectly. Six different frames were identified: the morality frame, health and social frame, security and public order frame, economic and fiscal frame, institutional frame and the citizens’ frame. Only the first of these frames may be defined as displaying uniquely moral qualities. Of these frames, two are idiosyncratic – the institutional frame, notable when local politicians emphatically blame the national level for the negative effects of gambling, and the citizens’ frame with its populist flavour and electoral appeal. Both frames are imbued with paternalism, positioning them in the moral frame/instrumental frame divide.

Our contribution extends the academic literature on gambling as a latent morality policy and reinforces the proposal that the scholarly definition of the status of an issue as moral is significantly related to the temporal and geo-political context of the cases studied. Gambling in Italy, and this may be true for a variety of issues, cannot automatically be defined as a latent morality policy.

Methodologically, the coherent content analysis proposed here is a response to a lack in current approaches. Our methods demonstrate that framing processes are diversified in the various political arenas studied, and our results show that the exploitation of morality frames is directly influenced by the multilevel treatment of an issue in parliamentary debates and public debates. These multilevel treatments result in extremely differentiated frames which reflect an interaction with related policies and the perceived moral nature of the phenomenon. Our research demonstrates that an understanding of the constraints on the framing processes is crucial in determining the exploitation of morality frames.

This essay was limited by three important constraints which will form the basis of future research direction. The first is the geographic context. This analysis of a single country requires to be expanded in order to attempt a comparative approach. We feel it is crucial to verify the existence of country-specific frames in other national contexts and assess these frames in detail for their epistemological implications and challenge to the theoretical division put forward by Mucciaroni (Reference Mucciaroni2011). The second limit lies in the use of interviews displaying the policymaker’s points of view. This method represents an extension to those used to date in research on morality policies, and its potential needs to be developed further. For example, the accounts of the actors whose influence contributed indirectly to the policies could be considered. We maintain that, with a broader sample of countries and an approach strongly based on qualitative interviews, an analysis of morality policies together with COSs would generate a fruitful path for future research. Finally, a wider set of policies and cases should be utilised to better clarify the relationship between COSs and frames. We still consider the presence of favourable COSs as a necessary but not sufficient condition for the activation of morality frames. However, the mere presence of favourable national COSs is not able to translate into an activation of morality frames, a finding coherent with the general trend and in line with the wider debate on normalisation. For this and the reasons noted above, we confirm the need to broaden the empirical analysis to further States, both for gambling and other latent morality policies.

Acknowledgements

The research was conducted by the Università Cattolica of Milan and financed by the Italian think-tank Fondazione per la Sussidiarietà.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X19000345

Data Availability Statement

This study does not employ statistical methods and no replication materials are available.