Abstract

Co-creation is a common term used in place branding to describe the involvement of stakeholders in the creation of a place’s brand. The motivation behind co-creation is that it will add depth and legitimacy to the brand. Through a process of co-creation, it is also hoped that stakeholders will become active ambassadors of the brand and its values. Co-creation, however, is far from simple in practice—places are complicated, budgets are often small and competing interests are many. This paper examines the processes of co-creation that were initiated by Plett Tourism, a tourism office in a South African seaside town called Plettenberg Bay. By considering this case study, and case studies from other places, it is hoped that a broader conception of co-creation can be understood, one that goes beyond the early stages of involving stakeholders in the creation of a place brand and instead creating a platform for continuous engagement with stakeholders. Part of this engagement is sometimes called internal place branding, and so the ways in which internal place branding intersects with co-creation will discussed in this paper too.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plettenberg Bay, affectionately named ‘Plett’ by locals and tourists, is a upmarket tourist destination on the southern Cape coast. This paper examines the activities of the local tourism office, Plett Tourism, between 2010 and 2016 when it created a new branding strategy and visual identity for the town.

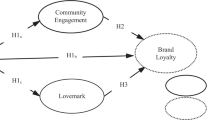

This case study brings two issues that are prevalent in literature about place branding into focus: namely, co-creation and internal place branding. In literature about place branding, the term co-creation describes a process of including stakeholders in the branding of a place (Anholt 2008; Casais and Monteiro 2019; Kazaratzis 2012; Ntounis and Kavaratzis 2017). The importance of creating a brand and identity that resonates with the community it represents is repeatedly raised in critical literature because if local stakeholders identify with a place brand, then they are more likely to be ambassadors of that place (Braun et al. 2013). This adds legitimacy to the brand and helps it perform one of its primary functions—attracting tourists and inward investment (Braun et al. 2013).

Yet, there is no clear roadmap for the involvement of stakeholders and there remain several challenges. The most obvious being that a place—a neighbourhood, city or region—can have thousands, if not millions of stakeholders, and so meaningfully engaging with those stakeholders is difficult. A second challenge articulated in the literature on place branding is that much of the stakeholder involvement is focused on the early stages of place branding development (Zenker and Erfen 2014). Both issues will be discussed in detail in this paper.

When focusing on co-creation and local stakeholders, place branding recognises that ‘brand management is first and foremost an internal project’ (Anholt 2008). Internal place branding is branding focused on communicating with residents instead of external parties. Yet, the intended outcome is not dissimilar to co-creation: it attempts to get the place brand to resonate with residents and cultivate a sense of community and encourage them to become “brand ambassadors”. Both co-creation and internal place branding provide a way for place branding to become something of strategic depth and value, rather than a set of brand guidelines that do not meaningfully reflect the place being branded.

Of particular focus in this paper, is the idea that co-creation and internal place branding can a provide a platform for the continuous inclusion and engagement of stakeholders beyond the early stages of establishing the place brand.

This case study of Plettenberg Bay does not seek to offer a definitive direction for stakeholder involvement in place branding, but rather to add another case study to existing literature in order to better understand the significance, opportunities and challenges of co-creation and internal place branding. It is also hoped that the paper will help broaden the definition of co-creation by identifying the ways in which co-creation is present in internal place branding.

This paper is structured as follows. To start, a theoretical framework is established that defines ‘co-creation’ and ‘internal place branding’. Then several case studies are examined that highlight different approaches to co-creation. Place branding in South Africa is then discussed in broad terms before Plettenberg Bay and the work of Plett Tourism is assessed, in light of the case studies previously examined.

In conclusion, this paper hopes to illustrate that co-creation and internal place branding are not mere buzzwords. However, limited budgets are, and, however, divergent the mediums of participation may be, seeking to meaningfully engage with members of the community in the creation of a place’s identity may not only result in greater economic benefits from tourism, but also may help foster a sense of community and social cohesion.

Theoretical framework

Defining co-creation and internal place branding

Much of the literature on place branding emphasises that it ought not to be considered a merely surface-level campaign of creating straplines and graphics, but rather that successful place branding engages stakeholders and the place it represents on a deeper, more substantial level (Anholt 2008; Ntounis and Kavaratzis 2017). In a place with such a young and contested national identity as South Africa, the importance of a strategy that is not merely skin-deep but instead rooted in the community it represents, could be considered of extra importance.

Part of what this engagement constitutes is involving stakeholders in the ‘co-creation’ of the brand. Co-creation, when used specifically in marketing, can be understood as part of a much broader shift from a goods-dominant logic of value, where one party produces value and the other consumes it, to a service-dominant logic, where both producer and consumer are instead involved in the reciprocal co-creation of value (Vargo and Lusch 2008). The ways in which consumers co-create value, Vargo and Lusch argue, are by ‘enhancing brand and relationship equity for the firm, either directly or indirectly, through influencing the attitudes, the making of meanings, and the behaviour of others towards the firm’ (2008). A service-dominant logic is preferable as it emphasises the possibility of a mutually beneficial relationship—a ‘win–win’ situation for both producer and consumer.

Marketing in the tourism industry has experienced the same shift, with far greater emphasis placed on the dialogue between tourists and the people who live in the place they are visiting (Liu et al. 2021). This paper focuses on the organisations that create the actual place brand for a tourism destination—usually the local tourism office.

The second term that is used in this paper is ‘internal place branding’. Internal place branding, or internal place marketing, is a concept that is less prevalent in the literature on place branding yet overlaps with co-creation, both in practice and objectives. If external place branding can be defined as marketing a place to attract tourists and investors, then internal place branding is to sell the place to its own residents (Casais and Monteiro 2019). The reason co-creation and internal place branding can be linked is that the motivation for doing either is often the same: the belief that successful place branding needs the brand to resonate with residents and other stakeholders if they are to be ambassadors for the brand and thus embody it. The closer the values of the brand are aligned with those of the residents—for example, environmental, cultural or economic values—the more coherent the expression and experience of a place can be.

Importantly, the time at which co-creation may occur is not limited to the beginning of the process. Co-creation can come at various stages and take on different forms. Zenker and Erfren (2014) argue that co-creation can be divided into three stages: Stage 1 is ‘defining a shared vision for the place including core place elements’; Stage 2 is ‘implementing a structure for participation’ and Stage 3 is ‘supporting residents in their own place branding projects’. The next section makes use of Zenker and Erfren’s three stages as a helpful framework to understand which elements of co-creation are being employed in each case study.

Case studies: from Blufton to Bogota

This section of the paper will look the co-creation of a place brand through multiple case studies. The scope is deliberately broad in terms of population size, ranging from towns of a few thousand people, to a city of millions. Geographically, the scope is broad too with towns looked at in North America, South America and Europe. Case studies have been chosen where the strategy of engagement is of interest, rather than trying to find towns with similar sized populations, or places geographically close to Plettenberg Bay.

In a study conducted in Blufton, South Carolina it was noted that stakeholders were included in a process of co-creation through four charettes of 25–30 people (Hudson et al. 2017). A project in Carvalhal de Vermilhas, Portugal made a documentary, turning to video because of its ‘heuristic and collaborative potential’; 11 participants were found, and a series of comprehensive interviews were conducted during walks, over dinner and on camera (Rebelo et al. 2019). In a study in Bogota, 80 in-depth interviews were conducted with local stakeholders and 12 thematic focus group workshops were convened that concentrated on important themes in the city, including the economy, tourism, culture and urban development (Kalandides 2011).

These three case studies engaged with a small number of residents relative to the overall population of the place being studied. This is an inherent challenge in participatory processes in place branding as the places being branded are invariably large and possibly unwieldly (streets, cities or nations) and the budgets with which they are to be branded are often far smaller than corporate branding budgets (Jacobsen 2009). Blufton in South Carolina for example had a population of 13,074 in 2016 (United States Census Bureau) while Bogota, Columbia, the largest city this essay considers, had a population of 7.35 million people in 2011 (Guzman and Bocarejo 2017).

However, whether the consultation process was or was not exhaustive is not the focus of this paper. Part of the reason for this is that even if a budget was in place that could lead to a consultation process involving a significant portion of a places’ stakeholders, it seems likely that the broader the pool of interviewees, the broader the opinions on the place.

Indeed, the difficulty of finding consensus is demonstrated by a study conducted by Ntounis and Kavaratzis as part of the HS2020 campaign in Britain that sought to understand how to rebrand British High Streets. In a series of workshops that were conducted with local stakeholders in Alsager, it became evident that the ways in which the town had changed ‘might have led to confusion between local stakeholders about what type of town Alsager is and what town they want it to be in the future’ (Ntounis and Kavaratzis 2017). Interestingly though, Ntounis and Kavaratzis claim that they were heartened by the high level of engagement of local stakeholders and the perception that residents of Alsager ‘felt that the place brand was embedded in their own personal values’ (Ntounis and Kavaratzis 2017). This suggests that even if there is little consensus on what the purpose of the brand is, the process of co-creation itself can lead stakeholders to feel comfortable with the brand.

Despite differences in size, the examples from Blufton, Carvalhal de Vermilhas and Bogota all share a common approach, where the values or identity of a place are understood by directly consulting a limited number of stakeholders through qualitative research methods such as interviews, or less traditional methods such as documentary-making. Yet, these three examples are all focused on the initial stages of the branding process, the creation of the brand. These could all be said to be part of Zenker and Erfen’s stage 1.

Zenker and Erfen (2014) define stage 2 as ‘implementing a structure for participation’ in which stakeholders can receive funding for their own projects that align with the broader place brand strategy.

This idea seems to overlap with stage 3 of Zenker and Erfen’s strategy: ‘supporting residents in their own place branding projects’ (Zenker and Erfen 2014). One such example that Zenker and Erfen draw attention to is in Hamburg where the internet was utilised to create a platform on which stakeholders could access ready-made press texts for free, as well as photographs and promotional material templates (Zenker and Erfgen 2014). Thus, the city has created a system in which continuous forms of participation can take place as well as where residents are supported in their own place branding projects.

When branding Digbeth, a neighbourhood in Birmingham, London-based branding agency DNCO, in collaboration with type foundry Colophon, created a unique freely downloadable typeface, Digbeth Sans. This offers a form of ongoing engagement with the community and provides a simple form of support in which stakeholders can connect their own business, event or project to the broader brand strategy and identity. It could also be said that these activities go beyond mere involvement and can help get stakeholders to ‘own’ the brand: as DNCO write, the freely available typeface ‘Digbeth Sans’ has been created to be used by people in the area, making the place brand own-able by the community it represents’. (https://dnco.com/work/digbeth). This is an example of where co-creation is present in internal place branding.

Braun, Kavaratzis and Zenker point to an interesting example of internal place branding in Berlin and the ‘be Berlin’ campaign. Launched in 2008, the campaign included an online platform where citizens could upload stories and thus be the multiple voices of the city (Braun et al. 2013; Colomb and Kalandides 2010).

‘be Berlin’ and the city’s focus on internal place branding is interesting not only because it is regarded as a successful instance of internal place branding, but because Berlin was one of the most famously divided cities of the twentieth century prior to the Berlin Wall coming down in 1989. Significantly, ‘be Berlin’ has been noted for its inclusion of previously underrepresented identities in Berlin, such as Turkish Berliners, and as Kalandides & Colomb note, the “’be Berlin’ campaign clear[ly] seeks to address social divisions through an appeal to a collective identity feeling (‘Wir-Gefühl’) with a broad, inclusive scope’ (Kalandides and Colomb 2010).

An example of this inclusiveness can be found in the brand itself, ‘be Berlin’. This was often preceded by two other lines of text, an example being ‘be Open, be Free, be Berlin’ (Kalandides and Colomb 2010). This allowed the strapline to be adaptable. But, more significantly, the strapline did not specify what Berlin is or ought to be, but rather remains ambiguous and open-ended.

A similar strategy, of creating an adaptable brand, was employed by one of the most successful logo creation campaigns of recent years for the Portuguese city of Porto, which won numerous awards including the European Design Awards in 2015. The logo is blue and white and has different symbols of the city, including a wine glass and prominent historical architecture, composed to form a pattern. After conducting a focus group with seven participants, the study revealed that ‘All the participants said that they identify the brand identity with the city identity, since it shows a great symbolism and depicts memories of their lives’ (Casais and Monteiro 2019). Yet, interestingly, the logo was not created using a process of co-creation but rather by a local design studio, Studio Eduardo Aires, who state that the pattern echoes the azulejos or blue tiles that are common in the city (Studio Eduardo Aires, 2021). The intention of the logo, the designers state, is that icons that are no longer relevant can be removed and replaced by new ones.

One the one hand the logo is cleverly rooted in Porto’s identity, while on the other hand, like the slogan ‘be Berlin’, it is an adaptable and open-ended identity for just as words can be slotted into the pattern ‘be… be… be Berlin’, so new icons can be inserted into Porto’s logo.

This points to a strategic element in successful place branding. While engagement with stakeholders is important, the scale and challenge presented by trying to brand cities, and the divergent opinions of the inhabitants of those places, means that a successful place brand is open to change.

The success of the Porto brand and logo could in part be said to be a result of two aspects: on the one hand, the design of the brand is rooted in the local design heritage of the city, while on the other hand, the design is open-ended and adaptable, allowing for a process of limited yet continuous co-creation, and that this process itself can be a tool for building civic pride and social cohesion.

Co-creation and internal place branding are not mere buzzwords then. However, limited budgets are, and, however, divergent the mediums of engagements may be, seeking to meaningfully engage with members of the community in the creation of a place’s identity may not only result in greater economic benefits from tourism, but it may help foster a sense of community and social cohesion.

These dual benefits of meaningful place branding are especially relevant in South Africa, a country that remains deeply socially, politically and economically divided. Place branding can provide for continuous engagement and cooperation that can not only help create a brand for a community but be a tool for the creation of community itself. While it is difficult to measure how much place branding can result in establishing social cohesion, the possibility that it can is enough of a reason to undertake place branding responsibly, and part of this is through co-creation and internal place branding.

The next section, will outline and then analyse the place branding strategy undertaken in Plettenberg Bay in terms of co-creation.

Place branding in Plettenberg Bay, South Africa

Place branding and its context in South Africa

South Africa is an intriguing place to study place branding. Since emerging from apartheid in 1994, South Africa has created a new national identity to reflect a new society—from a new flag to a new coat of arms to new government buildings. This is a project that continues to this day. Yet the legacy of apartheid is apparent in many South African cities and towns. Indeed, Plettenberg Bay is still largely divided along racial and economic lines with the hopes of the ‘Rainbow Nation’ often at odds with its reality. It is in this charged landscape that place branding takes on an added dimension as a platform not only for economic opportunity in a place that desperately needs it, but also as a platform on which identity is created and contested.

The rebranding of the country was itself a means of representing the radical societal and political change that occurred with the election of Nelson Mandela in 1994, which signalled the transition of South African society from a country controlled by white minority rule to a democracy. While South Africa’s social and political identity is still being constructed as colonial-era statues are removed and streets and towns renamed, a significant amount of energy has been dedicated to creating an identity to attract investors and tourists.

In August 2000 a Public Private Partnership, the International Marketing Council of South Africa or Brand South Africa, was established to help grow South Africa’s identity globally and domestically (Youde 2009).

Brand South Africa represents one of the country’s most significant branding efforts, while it’s the most significant branding event in the country was certainly the hosting of the FIFA World Cup in 2010. While the final expenditure is not clear, experts suggest it was between R60 and R100 billion, or $8 to $30 billion (Fullerton and Holtzhausen 2012). South Africa was clear that part of the motivation for hosting the event was to improve the country’s brand image (Knott et al. 2015; Fullerton and Holtzhausen 2012). At the time the event was to have the largest television audience of any sporting event ever (Knott et al. 2015).

However, whatever emphasis was placed on building the country’s brand, an objective in hosting an event on this scale are the tangible benefits, including job creation, infrastructure development and the significant growth of tourism, both as visitors for the event and subsequently. Although the event did bring 310 000 visitors and $510 million into the country, this fell short of overall expectations (Fullerton and Holtzhausen). The number of visitors to South Africa was less than anticipated and it has been argued that this was in part due to negative press coverage that painted an exaggeratedly dangerous picture of South Africa to potential tourists (Hammett 2014). Whatever the validity of these arguments, what can be accepted is that South Africa has a complex and multi-faceted identity that offers benefits, as well as risks, to potential tourists.

South Africa’s brand therefore needs to respond accordingly. South Africa was one of the few countries in the world to develop a ‘nation brand umbrella’ (Bowie and Dooley 2005). In this instance the country has a brand architecture with layered categories. A well-known example of brand architecture in place branding that Bowie and Dooley point to is Spain’s ‘house of brands’, organised by a national or ‘master brand’, Espana, with regional brands such as Catalunya Turismo beneath it, and individual city brands beneath that Turisme de Barcelona (Bowie and Dooley 2005).

The focus of this paper, Plettenberg Bay’s tourism office, would fall hierarchically if not officially under the provincial brand Western Cape Tourism, then South African Tourism, and finally, Brand South Africa. The importance of tourism to the country is clear. From a national perspective, the direct contribution of the tourism sector to GDP was ZAR 130.3 billion in 2017, which translates to 2.8% direct contribution to the GDP (http://www.statssa.gov.za). Tourism in the Western Cape—the province that Plettenberg Bay sits within—has ‘grown faster and created more jobs than any other industry’ according to the government’s Department of Tourism (https://www.gov.za/about-sa/tourism#). South Africa has been negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic with foreign arrivals dropping to zero at its lowest point (https://tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/tourist-arrivals).

Numbers are now increasing but in a country that suffers from high levels of unemployment and in which millions of people live below the poverty line, the economic importance and potential of tourism—and therefore place branding—cannot be overstated.

Plettenberg Bay and Plett tourism

Plettenberg Bay lies roughly at the centre of South Africa’s southern coastline. It has, by almost any measure, spectacular natural scenery with mountains overlooking a bay of long sandy beaches. In the last few decades, it has developed a reputation as a favourite beach holiday destination for the ‘rich and famous’. This has exaggerated the gulf in social cohesion between mostly white wealthy visitors, and mostly poor black workers. The branding described therefore has to be seen against the backdrop of the legacy of apartheid, the slow progress made in economic transformation in smaller towns such as Plettenberg Bay and thus the continuing marginalisation of black citizens from the control and ownership of the town’s economy, and consequently, the often-negative approach adopted by many residents towards the ‘brand’ and ‘tourism’ in general.

Plettenberg Bay had a population of 49,162 people in 2011, according to a national census (https://www.statssa.gov.za). At the time of writing this paper in 2022 a new national census is being conducted and it is anticipated that the population will be greatly increased—in fact, the municipality’s population was estimated at 67 139 by the Municipality and Western Cape provincial government in 2018 (Western Cape Government https://www.westerncape.gov.za).

The rapid increase is due, primarily, to the strong migratory patterns of people from municipalities in the Eastern Cape province to the Western Cape province (Jacobs and Du Plessis 2016). Plettenberg Bay is arguably the first significant municipality in the Western Cape, and records above South African average rates of economic growth. People moving to Plettenberg Bay or passing through to other towns in the Western Cape from the Eastern Cape are mostly doing so in search of better opportunities for themselves and their families.

While almost all the people coming from or through the Eastern Cape are looking for work and are generally poor, Plettenberg Bay is also attracting working people relocating from inland cities, a process called “semi-gration” which has accelerated since Covid-19 and the growth of working remotely.

Plettenberg Bay is thus at once on the edge and at the centre of dynamic migratory patterns, and the constant movement of people creates both opportunities and complexities which the town must resolve in its place branding strategy.

When the Plettenberg Bay tourism office, Plett Tourism, undertook the rebranding project, it recognised the opportunity to better reflect the ambitions of the New South Africa by making this brand more inclusionary and democratic. By examining promotional literature, presentation decks, social media, and activities of the Plett Tourism office during this period of rebranding—between 2013 and 2018—this section attempts to draw out elements of co-creation and internal place branding.

The first public release of Plett Tourism’s new brand identity was in the form of a promotional newspaper in August 2013 that was distributed throughout the town. The front cover had the new graphic identity and strapline, ‘Plett It’s a Feeling! along with the subtitle ‘Introducing a brand new logo for Plett… And what it means to you!’ (Plett It’s a Feeling, 2013).

This document is representative of what could loosely be categorised as fitting into stage 1 (‘defining a shared vision for the place including core place elements’) of Zenker and Erfen’s three-part strategy (2014).

In the copy included in this promotional newspaper the Plett Tourism office wrote: ‘we came to realise that Plett was more than a place, but a feeling you get when you experienced the place’ (Plett It’s a Feeling, 2013).

While it is emphasised in the literature that focusing on logos and straplines at the expense of a brand that connects to stakeholders more deeply is a common pitfall in place branding, it would be a mistake not to recognise the importance of the logo and strapline and so it is worth examining (Anholt 2008).

The Plett tourism logo shares several similarities with the Porto logo. The first is that the process of creating the Plett logo, like that of creating the logo and strapline of Porto, was not done through a process of co-creation by a large number of stakeholders but instead by members of the Tourism Office and a local graphic design studio.

However, it is strategically like the Porto logo and Berlin strapline in that it is open-ended, defining an experience rather than a product, as it does not define Plettenberg Bay per se. As a start, this is a simple way of creating a structure for continuous engagement simply by not excluding stakeholders by defining the town in definitive terms.

Another significant aspect of the initial newspaper was that rather than merely introducing the place brand ‘Plett’, place branding as a concept was itself introduced. The first section of copy introduced the project of Plett Tourism’s rebranding and went as follows:

‘If Paris is about romance, and Milan is style, Barcelona is culture and Rio is fun, what then is Plett? And does it matter? Well, it does because these are place brands, and they mean something to those who live and visit and invest in them. They attract people because of what they are and how they do things. Place brands reflect history and point to a future, and Plett’s no different. So, what’s Plett about? And do we all share a vision of what Plett should or could be?’ (Plett It's a Feeling!, 2013).

This invites stakeholders to directly consider the strategy of the tourism office. The promotional newspaper also affirmed that the Tourism Board was intent on consulting stakeholders in the town. It then went on to state that Plett Tourism had already consulted with ‘50 or so business, community and political leaders’ and that they were ‘going to consult with a wide range of stakeholder groups in the months ahead’ (Plett It’s a Feeling, 2013). This is qualitative research not dissimilar to that undertaken in Blufton, Carvalhal de Vermilhas and Bogota.

This could all be seen as fitting into Zenker and Erfen’s stage 1. The second stage, implementing ‘a structure for participation’ was also initiated by Plett Tourism by establishing four strategic themes that were anchored by an event and the publication of a magazine: Plett Summer was created to house a wide range of activities and attractions during the primary holiday season; Plett Adventure & Nature sought to position Plettenberg Bay’s spectacular geography and wide range of adventure activities; Plett Wine & Food showcased the region’s growing wine and artisanal food industry; and Plett Culture & Heritage created a platform to showcase the region’s rich, but previously largely neglected, cultural history. These four strategic themes helped communicate Plettenberg Bay’s brand values. Over and above the programme developed by Plett Tourism, residents from the town could apply to have an event or project supported by Plett Tourism provided it aligned with one of the four themes. Applications were made by physically visiting the Plett Tourism office located in the town centre or by accessing an online application form on the Plett Tourism website. It is worth focusing on two events to better understand this strategy, namely namely Plett Wine & Food, and Plett Culture & Heritage.

The event that anchored the theme Plett Wine & Food was the Plett Wine and Bubbly Festival. Events are often intrinsically linked to a place’s identity and brand, representing the town’s values, attributes and culture and well-known examples include the Edinburgh Fringe Festival or Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Yet, it is a common aspect of place branding to create events to attract tourists and engage with residents. Blichfeldt and Halkier (2014) write about a small Danish town, Løgstør, that created a mussel festival as a ‘signature event’ around which it built its brand identity. The authors argue that while the festival was not intended as a community-building exercise—indeed organisers pointed out that the town has a fair that fulfils this function—it has ‘strengthened identity and pride’ through the manner in which it involved local residents through being employed, as volunteers and indeed as festival goers (Blichfeldt and Halkier 2014).

An event like Løgstør’s oyster festival could then be said to provide the scaffolding in which stakeholders can contribute to the formation of the identity of the town. Each of the four events that Plett Tourism established attempted to do the same thing.

Plett Wine and Bubbly Festival both positioned and promoted the Plett Winelands, an increasingly important economic and tourism sector in the town. Wine, perhaps because its taste and character is so tied to the climate and soil in which the vines are grown, is a powerful place branding tool—best exemplified by ‘champagne’ and its eponymous town. South Africa itself is a large exporter of wine and it supports a thriving tourism industry predominantly around Cape Town.

The Plett Wine and Bubbly Festival was strategically positioned to nurture this young viticulture industry, thus providing a much-needed new form of local employment. Like the event in Løgstør, the Wine and Bubbly Festival created a scaffolding for co-creation by engaging with a wide number of stakeholders in the community: from winemakers to staff employed as waiters, to local musicians, and of course, residents attending the festival. Importantly, the event tapped into the existing brand equity Plettenberg Bay has by appealing to wealthy tourists.

Viewed through a critical lens, it could be argued that events like these can further exaggerate the discrepancy in wealth in the town, and reinforce the idea that tourism is the preserve of an elite. Yet, paradoxically, the wine industry is creating employment and opportunity for previously marginalised people. More importantly, great care was taken to ensure a sizable portion of attendees at the festival came from previously marginalised communities via special invitation. In this way, the festival reflected the diversity of the town and aligned with a key objective of the place brand strategy, namely inclusivity.

The strategic theme that provided opportunities to broaden the tourism offer by speaking directly to Plettenberg Bay’s history, as well as its complicated present, is Plett Culture & Heritage.

The event that anchored this theme was the Plett Arts Festival whose 2018 programme included educational events—the Plett Winter School—where locals could learn about a range of subjects ranging from African music to printmaking. Plett Afrojazz was a live music event on one of the main beaches that brought together a diverse group of jazz musicians. Importantly, the event was free to attend. The Plett Arts Festival was also during the winter season when the town has the least number of tourists. The festival had a dual role of attracting tourists out of season while also taking the opportunity to engage with residents, making it a more direct form of internal place branding. It is clear, however, that the Plett Arts Festival was an event limited in influence and could only be a small part of a strategy of meaningful engagement.

A more ambitious project was introduced in 2018 during a presentation to the Minister of Tourism and the Mayor of Bitou Municipality (Presentation deck, Plett It's a Feeling! 2018) Plett Tourism presented a comprehensive tourism development proposal which covered all previously disadvantaged communities in the Municipal area.

The proposal included plans for a Cultural Centre that commemorated the original inhabitants of Plettenberg Bay, the Griqua people. The Griqua people are Plettenberg Bay’s oldest inhabitants and many residents of the town still identify at Griqua. Yet, it is a largely disavowed history, certainly during the town’s colonial and apartheid past, but even post-1994 the Griqua have not had their unique identity, and the way in which is it is connected to the history of Plettenberg Bay, properly celebrated. Unfortunately, the Cultural Centre in Plettenberg Bay still remains an unrealised ambition. Yet, the idea for the Cultural Centre has sound precedent in South Africa.

South Africa’s heritage and culture have proved to be a sustainable way for the country to diversify its tourism offer. Indeed, Viljoen and Henama (2017) write that, ‘Heritage and cultural tourism are notably one of the fastest emerging competitive niche tourism segments both locally and internationally’. South Africa is home to several significant sites that offer an insight into its past—one of the most famous being the the Cradle of Humankind. The country’s recent political past also draws thousands of visitors every year with 2018/2019 seeing 318,414 visitors to the Robben Island Museum, which oversees the management of the former-prison and UNESCO World Heritage Site that held Nelson Mandela (https://nationalgovernment.co.za).

These four strategic themes helped create what Zenker and Erfen would call stage 2, ‘a structure for participation’. Yet the website itself became a structure for participation. One example is ‘Wandsile’s Plett’ where a local writer from a previously disadvantaged neighbourhood was employed to write a column that was published both online and in print. This allowed residents to bring other perspectives of the town’s identity to light. As Wandisile Sebezo writes “We named this segment iKasi Life because we think Plett is more than its beaches, beautiful landscape, and wildlife. Let me remind you, dear reader, that I was raised in Kwanokuthula, a township west of Plett. There is a whole history of political and cultural activism in Kwano that, as a child, I was taught to revere,” (Sebezo, 2021). Thus, the publications and website funded by the tourism office created a platform for a far broader set of voices to continually participate the creation of the town’s tourism brand.

This brings us to stage 3 of Zenker and Erfen’s process: ‘supporting residents in their own place branding projects’ (Zenker and Erfen 2014). Plett Tourism invested in several smaller local events that were brought forward by members of the town, including fashion shows, music festivals and boxing tournaments. Sometimes the Tourism Office funded these projects but, owing to the limited funding Plett Tourism received, most of this support came in the form of marketing and strategic advice. While some of these events attracted tourists and could grow into events that increased the town’s tourism offer, the emphasis was rather on engaging with stakeholders in the town, processes described in a 2018 presentation to the Department of Tourism as ‘community outreach’ and ‘community tourism development’ (‘2018 Presentation to Minister Hanekom: 2018’). Yet, if internal place branding is understood to be a process of engaging with stakeholders to foster a sense of pride in the brand of a town, we could describe these activities as internal place branding.

By the end of 2018 the Plett Tourism brand had been well established. Non-tourism local government departments such as the Department of Waste Management had the logo and strapline printed on the side of the refuse collection vehicles. Local businesses such as supermarkets displayed the logo and strapline in their stores. On social media such as Instagram #plettitsafeeling was tagged 39.7 thousand times (27 June 2022).

A local football team received funding to manufacture its kit branded with the tourism logo and slogan. Local bars and restaurants, especially in poorer neighbourhoods or “townships”, received furniture such as outdoor umbrellas branded with the Plett: It’s Feeling! logo and strapline.

Six years later, despite changes in management, the board and municipal government, the tourism office still has the logo and strapline on its website and the four key themes continue to be used.

The objectives initially set by Plett Tourism were realised: “Plett It’s a Feeling” became both the signature for Plett’s tourism industry and a rallying point for its various communities. Most importantly, it was successful in drawing support from previously disadvantaged communities. The place branding undertaken by Plett Tourism thus served classic tourism marketing objectives, as well as helping build a sense of community inclusion, through co-creation and internal place branding.

Conclusion

The literature review shows that many critics are wary of place branding consisting merely of glib copy and passable graphics, rather than a thoughtful and responsible attempt to brand a place. The involvement of a place’s stakeholders in the branding process has been identified as an important mechanism to create place brands with depth. This is where co-creation as a term gathers momentum and becomes a key part of the good place brander’s toolkit.

However, there is a risk that the term co-create could itself become an uncritical practice and instead serve as a mere buzzword to describe a focus group or a handful of interviews (Franzen-Waschke 2021). Yet equally hand we can also broaden our understanding of the term co-creation, recognising the financial and logistical pressures on place branding.

In this paper, more traditional forms of co-creation have been examined that employ qualitative research methods, such as the place branding campaign in Bogota in which 12 focus groups and 80 in-depth interviews were conducted. While celebrating this, we can also recognise the limitations of this version of co-creation, when considering the Colombian capital is home to millions of people. On the other hand, the Porto logo was designed behind closed doors, something that goes beyond the grain of much of the literature on co-creation. Yet, residents in Porto who were interviewed in the study by Casais and Monteiro were said to ‘identify the brand identity with the city identity’, with some stakeholders going so far as to say that the symbolism incorporated into the logo reminded them of their childhood (Casais and Monteiro 2019). The design studio’s expertise and understanding of the place they were branding proved enough to create a successful brand that resonated with residents. While these two approaches in Bogota and Porto have limitations, both are meaningful ways of engaging with stakeholders.

be Berlin is similar to Porto in that it is also adaptable. Creating an adaptable brand, even if this is just the graphics or strapline, means that the brand invites a continuous process of co-creation. This supports Zenker and Erfen’s theory in which place branding is seen as a three-part process, in which initial stakeholder involvement and the creation of a graphic identity is only the first. The other two are: ‘implementing a structure for participation’ and ‘supporting residents in their own place branding projects’. Plett Tourism and the brand Plett It’s a Feeling! has this aspect in common with the Porto. campaign in that the brand is deliberately open-ended, and the identity of the town is not defined. This open-endedness can then be complimented by other strategies, such as the freely available Digbeth font, the promotional material Hamburg supplies to local businesses, or indeed the inclusive engagement which Plett Tourism encouraged. This points to a much broader conception of co-creation in which stakeholders can be continually invited to participate in the reshaping of a brand. It is important then that the brand itself is open and adaptable.

Continuous co-creation can also come in the form of internal place branding. Co-creation and internal place branding share many of the same objectives: to get stakeholders to become ambassadors of the brand and legitimising the brand through stakeholders taking ownership of it. Some internal place branding campaigns provide opportunities for stakeholders ordinarily excluded from the place branding campaign to be part of the co-creation of the brand. This is done by literally taking ownership of the brand—even if it is just being a set of outdoor umbrellas or a football kit—and thus being able to define in a small way what be ‘Berlin’ means, or what kind of ‘feeling’ Plettenberg Bay encapsulates.

In addition to the examples of Blufton, Carvalhal de Vermilhas and Bogota which used co-creation to establish a brand, we can look at other cities like Porto, Hamburg, Berlin, Digbeth and Plettenberg Bay that used co-creation and internal place branding to create a platform for continuous engagement, thus creating brands that resonate with the people they represent.

References

Anholt, S. 2008. Place branding: Is it marketing, or isn ’ t it? Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 4 (1): 1–6.

Blichfeldt, B.S., and H. Henrik Halkier. 2014. Mussels, tourism and community development: A case study of place branding through food festivals in rural north Jutland, Denmark. European Planning Studies 22 (8): 1587–1603.

Bowie, D., and G. Dooley. 2005. Place brand architecture: Strategic management of the brand portfolio. Place Branding 1 (4): 402–419.

Braun, E., M. Kavaratzis, and S. Zenker. 2013. My city – my brand: The different roles of residents in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development 6 (1): 18–28.

Casais, B., and P. Monteiro. 2019. Residents’ involvement in city brand co-creation and their perceptions. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 15: 229–237.

Collomb, C., and A. Kalandides. 2010. The ‘Be Berlin’ campaign: Old wine in new bottles or innovative form of participatory place branding? In Towards effective place brand management, ed. G.J. Ashworth. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Franzen-Waschke, Ute. ‘Co-Creation: Buzzword or a new philosophy of working?’ Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2020/06/24/co-creation-buzzword-or-a-new-philosophy-of-working/?sh=4cdbaaa92610. Accessed 6 Dec 2021.

Fullerton, J., and D. Holtzhausen. 2012. ‘Americans’ attitudes toward South Africa: A study of country reputation and the 2010 FIFA World Cup’. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 8 (4): 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2012.19

Guzman, L.A., and J. P. Bocarejo. 2017. Urban form and spatial urban equity in Bogota, Colombia. Transportation Research Procedia 25: 4491–4506.

Hammett, D. 2014. Tourism images and British media representations of South Africa. Tourism Geographies 16 (2): 221–236.

Hudson, S., D. Cárdenas, F. Meng, and K. Thal. 2017. Building a place brand from the bottom up: A case study from the United States. Journal of Vacation Marketing 23 (4): 365–377.

Jacobsen, B.P. 2009. Investor-based place brand equity: A theoretical framework. Journal of Place Management and Development 2 (1): 70–84.

Jacobs, W., and D.J. Du Plessis. 2016. A spatial perspective of the patterns and characteristics of main- and substream migration to the Western Cape, South Africa. Urban Forum 27: 167–185.

Kalandides, A. 2011. City marketing for Bogotá: A case study in integrated place branding. Journal of Place Managemet and Development 4 (3): 282–291.

Kazaratzis, M. 2012. From “necessary evil” to necessity: Stakeholders’ involvement in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development 5 (1): 7–19.

Knott, B., and A. Jones. Fyall. 2015. The nation branding opportunities provided by a sport mega-event: South Africa and the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 4 (1): 46–56.

Liu, Y., J. Li, and S. Sheng. 2021. Brand co-creation in tourism industry: The role of guide-tourist interaction. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 49: 244–252.

Ntounis, N., and M. Kavaratzis. 2017. Re-branding the High Street: The place branding process and reflections from three UK towns. Journal of Place Management and Development 10 (4): 392–403.

Rebelo, C., A. Mehmood, and T. Marsden. 2019. Co-created visual narratives and inclusive place branding: A socially responsible approach to residents’ participation and engagement. Sustainability Science 15: 423–435.

Vargo, S.L., and R.F. Lusch. 2008. From goods to service(s): Divergences and convergences of logics. Industrial Marketing Management 37: 254–259.

Viljoen, J., and U. Henama. 2017. Growing heritage tourism and social cohesion in South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 6: 1–15.

Youde, Jeremy. 2009. Selling the state: State branding as a political resource in South Africa. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 5: 126–140.

Zenker, S., and C. Erfen. 2014. Let them do the work: A participatory place branding Approach. Journal of Place Management and Development 7 (3): 225–234.

Websites

Department of Statistics South Africa. http://www.statssa.gov.za. https://www.gov.za/about-sa/tourism# Accessed 5 May 2021.

DNCO. https://dnco.com/work/digbeth. Accessed 6 Dec 2021.

Studio Eduardo Aires. https://eduardoaires.com/studio/portfolio/porto-city-identity/. Accessed 6 Dec 2021.

News 24. https://www.news24.com/news24/travel/locals-love-robben-island-again-record-tourist-numbers-hail-in-20th-anniversary-year-20170111 Accessed 6 Dec 2021.

National Government (South Africa). https://nationalgovernment.co.za/entity_annual/1936/2019-robben-island-museum-annual-report.pdf. Accessed 27 June 2022.

Trading Economics. https://tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/tourist-arrivals.

United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/data/developers/data-sets/acs-5year.html.

Sebezo, Wandisile. 2021 Wandisile’s Plett. https://www.plett-tourism.co.za/plett-tourism-and-mcfm-partner-to-bring-ikasi-life-stories-to-the-community/ Accessed 27 June 2022.

Presentations and promotional material

Promotional Newspaper. 2013. Plett It’s a Feeling!

Presentation deck: Plett It's A Feeling! Prepared for the Minister of Tourism, Honourable Derek Hanekom and his worship the executive mayor Peter Lobese, and all protocol observed'. 2018. on 12 October 2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author B, Simon Wallington, is the son of Peter Wallington, who was the Executive Chairman of Plett Tourism between 2012 and 2018. He has received no financial compensation for this from Plett Tourism. He is currently employed as a designer and strategist at DNCO, one of the branding agencies mentioned briefly in this case study. He has not received financial compensation from DNCO for writing this paper, as it was written while working as a researcher for Nicola Camatti.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Camatti, N., Wallington, S. Co-creation and internal place branding: a case study of Plettenberg Bay, South Africa. Place Brand Public Dipl 19, 525–534 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-022-00279-x

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-022-00279-x